City of Shadows: Why Los Angeles is the capital of noir

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry “Santa Anas” that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen.

In this gritty passage from his noir classic “Red Wind,” Raymond Chandler sets up an unmistakably tense relationship between a Southern California city and its tormented denizens. The short story is a definitive example of noir’s hard-boiled prose, filled with fast-talking dames, desperate grifters and hardened detectives.

Chandler and other archetypal noir authors such as James M. Cain (The Postman Always Rings Twice), Horace McCoy (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?) and James Ellroy (L.A. Quartet) drew their inspiration from what is the genre’s capital: Los Angeles. So, too, did iconic film noir, from classics such as Double Indemnity, Kiss Me Deadly and Sunset Boulevard to more recent acclaimed neo-noirs including Chinatown, L.A. Confidential and Mulholland Drive.

In all these works, L.A. is far more than a simple backdrop. Instead, the city assumes a leading role, becoming itself a major character in the dark dramas unfolding on its mean streets.

Marrying stylish European cynicism with raw American angst and originally written to be as disposable as the past lives of the ambitious dreamers who came to L.A. looking to reinvent themselves, noir’s appeal has endured for almost 90 years and shows no signs of abating. From the city’s shadowy past as a place awash in corruption and violent crime to a scandal-ridden movie industry that offered talented but poorly paid writers of pulp fiction the chance to finally strike gold, L.A. has much to inspire the genre’s writers and directors.

Sunlit paradise to disturbing dystopia

Noir, argues David Ulin, assistant professor of the practice of English, takes the mythology of L.A. as a golden land of endless opportunity and upends it. The genre represents the disturbing flip side of that urban paradise relentlessly promoted by the city’s boosters for more than a century as a sun-drenched utopia of sand, surf, palm trees, mountains and endless orange groves.

L.A. was healthy, its promoters claimed; it would cure you of all that ailed you. It was a place to throw off your past, to reinvent yourself, a city bursting with opportunity and imbued, of course, with the glamour of Hollywood. Come to L.A. and you might see a real-life movie star and — who knows? — if you were good looking and talented enough, even become one yourself.

All this was true — to a point — but as University Professor Leo Braudy notes, L.A., particularly in the 1930s and ’40s, was also home to a thriving underworld rife with bullet-riddled bodies, dope and prostitution rings, sensational murders, petty criminals, shady nightspots, illegal gambling joints, liquor and vice. Alongside the thousands of innocent — and frequently naïve — transplants from the Midwest and East, ambitious for a better life, were also the hoodlums and the crime bosses, the bootleggers, con artists, self-proclaimed saviors of the soul, and ladies of the night who set up shop in L.A., eager for a different kind of opportunity — an opportunity to prey on the gullible.

It was in this city of paradoxes and contradictions that noir flourished, offering in both literature and film a stylishly cynical vision of L.A.’s mean streets that reeks of disillusionment and alienation and yet still succeeds in seducing us, generation after generation, with its dangerous whiff of doomed, delusional romance.

Noir’s dark roots

Ulin defines noir as writing that grows out of Depression-era desperation and the sense that whatever promise the American dream offered has been betrayed in some way, stripped away or made unavailable by economic hardship.

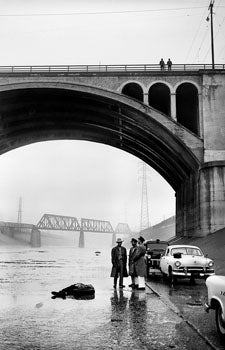

Detectives investigate a corpse found on the bed of the Los Angeles River, circa 1955. Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles Police Museum.

“Noir is what happens when a character is pushed beyond their limits to the verge of despair and is brought face to face with a universe that is, at best, indifferent and possibly malevolent, and how they deal with it.”

It is, he argues, the flip side of aspiration — the dark underbelly of an idealistic vision of prosperity, good health and self-fulfillment. Both noir and aspiration, he notes, coexist as a vital part of L.A.’s DNA.

“Noir is what happens when the aspiration is revealed as a lie,” he said. “L.A., of course, is the aspirational city because of Hollywood, and as we all know, even now to this day, it’s a city of mirrors. So, the idea that you come to L.A. to find opportunity then realize there is no opportunity, it’s the end of the road and you’re still in trouble and you can’t go home — that’s the root of noir.”

The detective and the city

Noir, Braudy says, is deeply connected to the idea of the city and both the detective’s intimate knowledge of it and his ability to move through it freely — allowing him to transcend place and class and us to experience L.A. fully as we follow his journey.

The archetypal example is Chandler’s existential hero, Philip Marlowe, who is required by his job as a private eye to visit both the mansions of the wealthy and the dive bars on Central Avenue.

In all these places, he’s an outsider, equally welcome and unwelcome, Ulin notes, citing Chandler’s memorable description from the opening chapter of Farewell My Lovely: “Even on Central Avenue, not the quietest dressed street in the world, he looked about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food cake.”

This simile, with two wildly disparate elements juxtaposed into one unlikely but striking phrase, is a wonderful expression of the city’s paradoxes, argues Braudy, Leo S. Bing Chair in English and American Literature and professor of English, art history and history.

“That’s very much L.A.,” he said. “And it’s very much the world that Chandler creates and that Marlowe inhabits. Chandler’s L.A. is the city of mean streets, not the sunshine city. He portrays L.A. as a world of facades and he wants to punch holes in those facades.”

Indeed, noir can be seen as a way to discover the city’s truth, Ulin argues, offering us a key to understand its hidden depths.

“Noir gives us the insider city, as opposed to the fantasy city,” he said. “In that sense, it opens up our sense of L.A. as a dynamic and complex environment.”

Where real life and fiction meet

That dark side of L.A. inspired generations of noir writers and filmmakers. There was certainly no shortage of material, particularly in the first half of the 20th century. In addition to L.A.’s notoriously corrupt police force and local government at the time, a series of high-profile Hollywood scandals and grisly murders, such as that of aspiring actress Elizabeth Short, known as “The Black Dahlia,” gripped the country and contributed to the city’s unsavory reputation.

“The city’s dark past is part of the background of noir and why films focus on L.A. as the place where all these things happen,” Braudy said. “It’s the city of shadows.”

L.A. remains both fascinated and haunted by its dark past, Braudy notes. The Millennium Biltmore Hotel, the last place Short was seen alive, still serves a Black Dahlia cocktail in her memory. Short’s sobriquet was inspired by a film, The Blue Dahlia, released the year before she was murdered — a prime example, Braudy says, of reality feeding off fiction, only for fiction to bloom again from reality.

“L.A. is a city of hucksters,” Ulin said. “It always was. It still is, in some ways.”

Another reason that noir flourished in L.A., Ulin argues, is the city’s populist aesthetic tradition.

“Because of Hollywood, there wasn’t the stigma about writing in popular forms, like science fiction or detective fiction, that there was in more established literary centers like New York City, where so-called literary writers looked down their noses at people who wrote in genre,” Ulin said.

As Chandler observed: “If my books had been any worse I should not have been invited to Hollywood and if they had been any better I should not have come.”

An enduring passion

Why has our fascination with noir endured? Braudy attributes our long-lasting love affair with the genre to its reflection of our fear of life going horribly wrong.

“Noir corresponds to a pessimistic view of the American dream, where the idea of failure is always present.”

However, Ulin argues that people like detective crime fiction because it suggests that — maybe — there’s a moral order to the universe.

“It’s a very compelling fantasy, and I think we turn to those kinds of books because they offer us some kind of consolation, or solace, in the face of chaos. But I also think the particular appeal of noir is that it doesn’t sugarcoat, and although it does resolve those stories, it does so in weird and ambiguous ways that make it feel truer to our experience of the world.”

Noir begins, he added, when hope is gone.

“Its aspiration is not to make you feel better, but to reflect the brutality of the universe.

“There are no happy endings in noir.”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2018/Winter 2019 issue >>