All I Need Is a Miracle

In March 2020, the governor of Puebla, Mexico, proclaimed that a vaccine for COVID-19 had already been discovered. To stave off the virus, he advised, simply tuck into a plate of mole de guajolote, a local specialty dish of turkey in a rich poblano pepper sauce.

Can I get a second dose?

Modern science blew us away with the speed and ingenuity with which it developed highly effective COVID-19 vaccines. But the pace of scientific innovation is no match for the pace of misinformation. From the earliest days of the pandemic, it has been easy to find a smorgasbord of unproven treatments, prophylactics and medical devices living somewhere between laughable pseudoscience and dangerous exploitation.

Hucksters develop sophisticated strategies to target receptive consumers, particularly on social media. You might not be the kind of person who would buy a colloidal silver solution that can turn your skin Smurf-blue, but what about a synergistic herbal blend that boosts immunity? Despite frequent warnings from doctors and scientists, the market for miracle remedies has been robust.

It’s a problem that transcends intellect or politics. The virus is scary, and most Americans have never lived through a more uncertain time. Even when we acknowledge that there is no good reason to believe exaggerated claims, good reason may not overrule any reason.

“People become very susceptible when their stress levels are high,” says April Thames, associate professor of psychology and psychiatry. “Resources in the brain that are typically allocated to problem solving get allocated to managing anxiety and we look for quick solutions.”

Across time and cultures, history bears out this truth. The anxiety we experience in times of crisis makes us vulnerable to con artists and quacks peddling recovery for their personal

enrichment. While most will agree that revival is best accelerated by a combination of empathy and expertise, plausible shortcuts have been proven to spark our innate desire for comfort on demand.

From the fabled “Fountain of Youth” to claims of weather manipulation to ubiquitous internet scams, history is filled with countless examples of shady actors offering miraculous cure-alls. That said, not all pseudoscience is crooked. Many offering unproven remedies aren’t villains with a scheme, but well-intentioned zealots with misguided hubris.

Not surprisingly, California has ties to some of the more colorful of these characters. With the help of USC Dornsife experts, we’ll get to know a snake oil salesman, a rain man and a frozen man whose “solutions” epitomized the problem.

CAN I SELL YOU A SECRET?

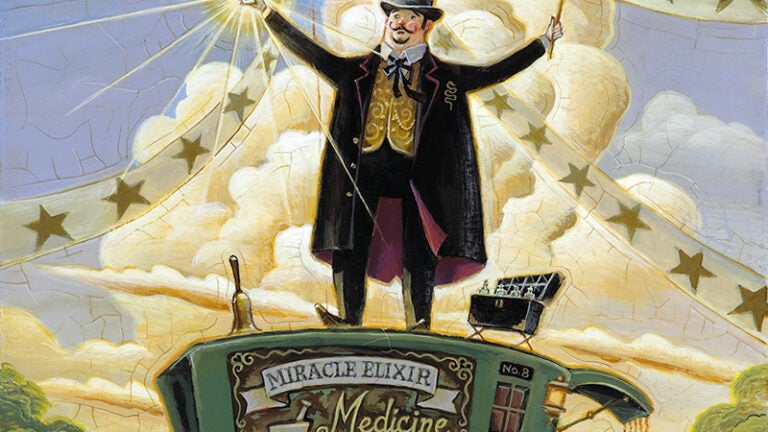

It’s the memory boosting supplement, the healing crystals and the cancer-killing tea. It’s snake oil — a catch-all epithet for the massive category of products that claim to treat ailments or improve lifestyle, despite having no fact-based medical value.

True snake oil, however, hasn’t always had a bad reputation. In the mid-19th century, Chinese immigrants arrived en masse in the American West, bringing their traditional snake oils for soothing aches and pains. The claims were not, in fact, far-fetched. The water snakes used contained a moderate amount of omega-3 fatty acids, compounds that have proven effective at reducing inflammation.

Like many nostrums arriving from parts unknown, it didn’t take long for snake-oil products to catch on. Enter Clark Stanley. Dubbed the “rattlesnake king,” Stanley toured the country by stagecoach, hawking his eponymous Snake Oil Liniment. A garish showman, he recognized that Chinese medicine would not seem as exciting or exotic as an elixir that leveraged the American West’s lingering mystique. Performing in a combination cowboy and Indian costume, he engrossed audiences with tales of two years spent with a Hopi tribe, from whom he claimed to have learned ancient healing practices.

It was just the warm-up act.

To the crowd’s amusement, Stanley wrangled a live rattlesnake from a sack. Handling the serpent like a child’s toy, he would rave about the medicinal properties of its oil before abruptly chopping off its head. Demonstrating his extraction process, the snake was boiled in a cauldron, causing fat to float to the top. Once mixed with Stanley’s proprietary formula, he claimed the oil cured “all forms of pain and lameness” from arthritis to reptile bites. We might assume that Stanley was not only the salesman, but also a client.

As his star continued to rise, Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment was sold around the country, finding its way into catalogues and drug stores. It took more than 30 years before the truth was revealed. In 1917, the United States District Court of Rhode Island, acting on analysis from the government’s Bureau of Chemistry, found that Stanley was misrepresenting his product. Not only was his liniment ineffective — rattlesnakes contain only trace amounts of the omega-3s found in water snakes — but snakes weren’t used at all. The product comprised a blend of mineral oil, cayenne pepper, camphor and beef fat.

“When strong claims are made backing up any product or method, that could be a red flag,” says Thames. “Scientists use cautionary statements and acknowledge there may be a subgroup of people who won’t benefit at all.”

Like many peddlers of patent medicines, Stanley walked away exposed, but wealthy. And before long, the snake oil salesman became an infamous mainstay of popular culture.

UNDER THE WEATHER

Health concerns are not the only problems prone to chicanery. Long before the global climate crisis became obvious, humans were concocting schemes to manipulate the weather as a remedy for stressed environments. Claiming they could coax moisture from the sky, a cohort of amateur scientists called pluviculturalists gained increasing public attention after the Civil War.

If anyone could turn skeptics into believers, it was Southern California’s own Charles Mallory Hatfield, who rose to fame early in the 20th century. With amphibious eyes and a vagabond fedora, he looked like someone Delta bluesmen meet at the crossroads.

As a young adult, he was a sewing machine salesman who grew increasingly fascinated with the pluviculture movement. Finding his father’s drought-stricken farm an ideal laboratory, Hatfield built 30-foot towers on which he evaporated chemical solutions, sending noxious fumes into the atmosphere. When storms finally brewed, they brought much needed revival to the suburban Los Angeles property. By 1904, he was contracting with local farmers and business leaders for services to “accelerate moisture” using a 23-chemical cocktail that remains unknown to this day — though one witness recalled that the air smelled as if “a Limburger cheese factory has broken loose.”

Although Hatfield insisted that he didn’t create rain but merely coaxed it from the clouds, his reputation quickly grew, earning him rainmaking gigs with cotton growers in Texas and mine operators in Alaska. According to the written account of his brother and rain-coaxing partner, Paul, every one of the nearly 500 jobs the pair accepted was successful. More than that, the work was guaranteed, as Hatfield would only accept payment after the contracted amount of rain had been measured.

This policy extended to a handshake deal Hatfield made with the San Diego City Council in 1915. Concerned that protracted drought would disrupt attendance at the city’s much-anticipated Panama-California International Exposition, the council agreed to pay Hatfield $10,000 to fill the Morena Reservoir over the course of a year.

“Escaping mortality is likely the oldest snake-oil scheme in the world. It’s a constant concern of humans everywhere — why can’t we live forever?”Within days, an evaporation tower was erected 60 miles outside the city. A week later, the skies opened up and would not relent. The torrent lasted 18 days, washing away bridges, inducing landslides and forcing downtown residents to navigate Broadway by rowboat. But this was only a prelude to the destruction unleashed when the nearby Lower Otay Reservoir burst under extreme pressure.

“A wall of water thirty feet high was released,” reported the Los Angeles Times on Jan. 29, 1916. “Sweeping down the valley, the great flood of water carried people, livestock and valuable property to destruction. Scores of residents were missing tonight.”

Meteorologists had predicted powerful storms up and down the Pacific coastline ahead of the commencement of Hatfield’s evaporation tower. In fact, historians suggest that most of the rainfall Hatfield claimed to facilitate was forecast by scientists or aligned with longstanding weather patterns. But many San Diegans pinned the destruction on Hatfield, some calling for his lynching.

“I don’t consider Charles Hatfield a quack or charlatan,” says Karin Huebner, academic director of programs at the USC Sidney Harman Academy for Polymathic Study, noting that he was a devout Quaker. “I think he was sincerely convinced of his concoction of chemicals, but I also think he studied patterns and may have had a special sense of weather.”

As for the $10,000 fee, Hatfield insisted he had delivered on the San Diego agreement. The council did not want to pay because acknowledging a contract would concede liability for millions of dollars in damages. Courts eventually ruled that the storms were an act of God, and Hatfield had little recourse but to continue attracting moisture elsewhere.

If nothing else, the great flood became a powerful marketing tool that helped Hatfield land opportunities as far away as Honduras. He worked until the Great Depression dried up business, forcing the prodigious rainmaker to pack up his secrets and hang up his umbrella.

HOPE SPRINGS ETERNAL

Elixirs, oils, vaccines, precipitation: Legitimate or loopy, the history of remedies for our existential problems are frequently related to fluids and moisture.

“To some degree, the idea of fluids is connected with life, whereas the opposite, dryness and desiccation, is associated with death,” says Professor of Anthropology Tok Thompson.

It explains the abundant folklore related to a fountain of youth found across cultures. The legend maintains that those fortunate enough to take in these waters would never grow older. More generous versions speak of reversing the aging process and restoring vitality and strength. Twenty-first century stand-ins for rejuvenating waters may come in the form of kale juice or age-defying skin creams, marketed as weapons against the ravages of Father Time.

“Escaping mortality is likely the oldest snake-oil scheme in the world,” Thompson says. “It’s a constant concern of humans everywhere — why can’t we live forever?”

If you have plenty of cash and even more patience, there’s a super cool answer to that question: cryonics. Cryopreservation is a pseudo-scientific process where immediately upon death, a body or brain is prepared, flash-frozen and stored in industrial vats of liquid nitrogen. The hope is that scientists will eventually figure out how to revive these individuals and have the cure to whatever it was they died from.

The industry started in 1967 when James Bedford, a University of California professor of psychology with advanced cancer, entrusted a trio — including television repairman and cryonics enthusiast Robert Nelson — to preserve his body upon death.

Bedford was placed in suspended animation and stored in various places in California, including his son’s home. Now in Scottsdale, Arizona, he continues to wait out the days among hundreds of individuals — including the head of baseball legend Ted Williams — and dozens of hallowed pets, preserved in one of four cryonics facilities around the world.

If it sounds far out, it is. According to Andrew Gracey, associate professor of biological sciences, it’s not just the fact that we don’t know how to revive these folks. We don’t know how to freeze them either. “For the process to have any real shot at working, it would require technology that can instantaneously freeze and thaw the body tissue,” he says.

The problem, Gracey explains, is thermal inertia. In the case of cryopreservation, it relates to the degree of slowness with which the temperature of tissue and cells become equal to that of the liquid nitrogen environment. As fast as the freezing process may seem, it’s not nearly fast enough to avoid damaging cellular structures.

“Life just doesn’t do well in that transition,” says Gracey.

Be that as it may, it wouldn’t kill you to try.