Talk the Talk

Bill Hader is breaking character again.

The comedian and actor, sporting an exaggerated mane of blond hair and an obvious spray tan, contorts his face as he struggles — unsuccessfully — to suppress his laughter. The cause of his impending outburst is his fellow Saturday Night Live cast member Fred Armisen emitting a string of words rendered nearly unintelligible by his farcical Southern California accent.

“I theenk yew shuhd geh hooome now, Devaaahn,” Armisen drawls, his own effort to stifle laughter beginning to show.

Barely a minute into the scene, Armisen’s camp, along with an equally ridiculous slur of extended vowel sounds from cast mate Kristen Wiig, proves too much, and the three actors are all but laughing out loud.

“The Californians” series of sketches have since become embedded in America’s pop culture — the above scene was viewed nearly 3 million times since it was uploaded to SNL’s YouTube channel in 2013. The skits satirize Southern California residents as vapid air-heads who frame most of their dialogue around driving directions.

But it’s the accent that makes the mockery work — an exaggerated version of “Valspeak” (short for “Valley Speak”) made popular three decades earlier by musician Frank Zappa and his daughter Moon Zappa with their hit song “Valley Girl.” Valspeak is attributed to residents, usually the teenage girls and young women, of Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley.

Like, toootally?

The defining characteristics of the caricatured accent seem to stem from three sources: pronouncing those vowels toward the front of the mouth; drawing out vowel sounds to a nearly absurd length; and using “uptalk,” ending sentences, and even phrases, on a high note, as if asking a question. (It also doesn’t hurt to insert the word “like” as frequently as possible.)

According to Sandra Disner, pronouncing the vowels toward the front of the mouth, though highly exaggerated in Valspeak, is common among Californians.

An associate professor (teaching) of linguistics at USC Dornsife, Disner is also a forensic linguist and an expert on accents. She has testified in numerous civil and criminal court cases, including a famous trial in the mid-1980s in which a man was acquitted of phoning in bomb threats against an airline when the caller’s thick East Coast accent was determined to be from Boston. The accused was from New York.

Disner notes that most native English-speaking residents of the Golden State display few defining accent characteristics but rather speak a somewhat featureless version of the language. Those attributes that do exist seem to stem from the positioning of the tongue in words such as “food” and “foot,” and from the merger of once-distinct vowels in words such as “caught” and “cot.”

“In California, we spread our lips, and we push our tongue frontward, which creates a shorter chamber for sound resonance,” she said, demonstrating with the word “food,” which she makes sound almost like “fuhd.”

Disner, born in New York, contrasts this with her native accent. “In New York, we pull our tongue way back and extend our lips to make a really long mouth.” As she demonstrates, “fuhd” becomes “foood” with a hint of a “w” just before the “d” at the end.

I am who I am, brah

So, if Californians in general speak with little or no defining tone, why then would an exaggerated accent such as Valspeak take root? Disner says the reasons may be social. Accents of any kind may have to do with residents’ pride in their home.

“They’re proud of being from Boston; they’re proud of being from New York; they’re proud of being from Southern California; they’re proud of being from the South,” she said. So rather than submit to a single American accent, they flaunt their local peculiarities and let it label them as belonging to a certain region. It becomes a part of their identity.

Disner also noted that accents tend to arise among young people. The young are more adaptive, more likely to adopt new traits than are older adults who are more set in their ways. A desire to foster inclusion among their peers also may reinforce young people’s use of a developing accent, which they might use to fortify their place within the group.

Andrew Simpson would agree, extending the principle to include vocabulary, as well. Simpson, professor of linguistics and chair of the Department of Linguistics at USC Dornsife, recently finished writing a new textbook focused on the role of language in culture, due out in January 2019 from Oxford University Press.

In the book, Language and Society: An Introduction, Simpson notes that language serves as an important representation of both individual and group identity. In other words, you are how you talk, dude.

Terminology that stems from daily life in “the Valley” — think “tubular,” “grody” and “totally” — as well as jargon from surfing and skateboard cultures and the film industry serve to identify the user as a Southern California denizen.

A fresh take

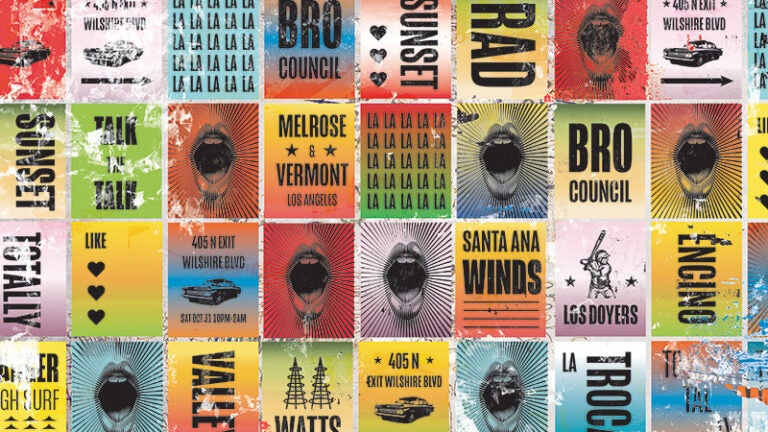

In her 2017 book, Talk Like a Californian: A Hella Fresh Guide to Golden State Speak, Colleen Dunn Bates (writing as Helena Ventura) catalogues California’s current popular lexicon, noting which region or subculture terms come from.

Most of the local vocabulary you’ll hear in and around L.A. seems to stem from surfing culture (that is, “surfspeak”) and Hollywood, with influence from Spanish language (think “Spanglish”) and more than a little hip-hop.

Words like “brah,” “insane” and “stoked” come straight from surfspeak. “Sup ey?” (“what’s up?”) and “la troca” (meaning “the truck,” as in the ubiquitous taco trucks found around the city) are popular terms pulling from Spanish and Chicano slang. And “the industry” (Hollywood) is its own pervasive beast. As Bates, a native Angeleno who studied journalism at USC from 1978 to ’80, writes in her book: “If you’re going to live in L.A., … you’re going to hear Hollywood slang, even if you never set foot on a studio lot.”

Hollywood clearly contributes significantly to the popularity of Valspeak, surfspeak and other L.A.-area language. Films such as 1983’s Valley Girl, no doubt inspired by the Zappas’ song a year earlier, kept up the Valspeak momentum, and more than a decade later, the success of Clueless, a cult classic to this day, assured Valspeak’s position as a mainstay of popular culture — witness again “The Californians,” popping up 20 years after Clueless.

Likewise, the music industry has proven a major influence, elevating surfspeak to national and even global standing. While surfing appears to have arrived in California in the early 20th century from Hawaii, the sport and its associated lexicon saw a rising tide of popularity in the 1960s, boosted in large part by the music of the Beach Boys, Jan and Dean, the Surfaris (the band actually put “surf” in their name!) and similar artists. Suddenly it was very cool to look, act and, of course, speak like a surfer.

Words like “gnarly,” “rad” and “epic,” which surfers had bandied about for years prior, were rapidly moving into the mainstream. Early Valspeak even drew from surfspeak — “tubular” refers to the interior of a breaking wave (a sick spot for a surfer to shred, but no place for a Barney).

Adopting jargon is common, according to Simpson, who notes that changes in language often arise when members of a group begin to admire and then emulate those among them with some level of status. Musicians with their celebrity would be a natural point of focus for the public, especially teenagers and young adults seeking to establish identities separate from their parents.

Legit or bogus?

Simpson also notes another important factor in developing a new way of speaking: Changes are often not so much invention as reinvention. Existing words are given new meaning and renewed life.

For instance, Simpson notes that “dude,” now nearly universal, actually originated in the late 19th century to describe a well-dressed person. It gained popularity among young fashionable Mexican Americans and African Americans in the 1930s and ’40s before surf culture, overwhelmingly young and white, co-opted its use. Show business then spread it everywhere.

Similarly, “rad” (short for “radical”), “epic,” and “shred” and most other words, all held meaning long before surfspeak came along, but surf culture nabbed them and skewed their meanings, creating new slang. Now “rad” is good, “epic” is even better and “shred” is to do really well or be exceptional or excellent.

It all may fade tomorrow, though. Valspeak, for instance, has dropped much of its lexicon. While the terminal uptick and extended vowels still apply, Valley dwellers rarely, if ever, utter “tubular,” “grody” (meaning gross), “fer shur” and “to the max.” Those terms are relegated to the linguistic dustbin. Others, including “like” and “all” (as in “I’m like”and “he’s all”) remain entrenched for reasons unknown.

“Slang and new expressions come into existence continually,” said Simpson, “but it is very hard, if not impossible, to predict which words will stick around and spread.”

He points to “groovy,” a very popular term from the ’50s and into the ’70s that is now completely out of fashion. But “cool,” he says, has made a major comeback after declining in popularity for years. “No one really knows why.”

Probably because it shreds.

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2018/Winter 2019 issue >>