ALUMNI INSIGHT

From patient to surgeon: How a childhood tumor shaped one doctor’s life and career

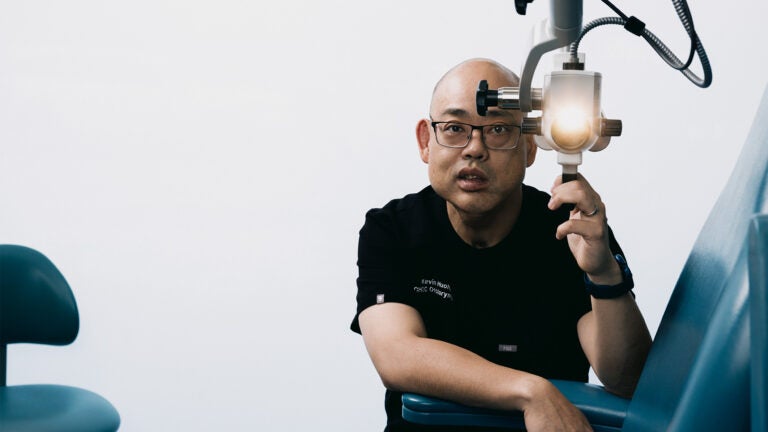

Pediatric surgeon Kevin Huoh ’03 joins me over Zoom from his home office, “or my man cave,” as he describes it, in Tustin, California, a stone’s throw from Disneyland. Clearly a proud Trojan, the specialist in head and neck tumors sports a cream jacket emblazoned with SC in cardinal and gold, while a framed photograph of the Los Angeles Coliseum is proudly displayed on the wall behind him.

When Huoh leans forward to adjust his screen, a large scar is clearly visible on his neck.

“I definitely have some surgical scars,” he says without embarrassment. “I have a hole in my neck from my tracheostomy tube. I also have two belly buttons — one was where I was connected to my mom, and the other,” he laughs, “was my gastrostomy tube.”

Huoh may have a sense of humor about his disfigurement, but when he was born, his chances of living at all — never mind living a normal life — were, as he says, “very iffy indeed.”

A Difficult Start

He was born with a benign tumor in his neck so large that it was obstructing his airway. Doctors initially gave his parents little hope for his survival. They placed a tracheostomy tube in Huoh’s neck to enable him to breathe and a gastrostomy tube in his stomach so he could receive nourishment.

The first six months of Huoh’s life were spent in the neonatal intensive care unit at Kaiser Permanente in Hollywood, just across the street from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA), where he would later spend significant chunks of his childhood. In the NICU, doctors advised his parents to place him in a skilled pediatric nursing facility — a course of action that Huoh says would almost certainly have led to his being institutionalized for life.

Fortunately for Huoh — and for his future patients — his parents rejected the doctors’ advice and took him home.

However, his ordeal was not over. Huoh may have escaped institutionalization, but his childhood was marked by dozens of surgeries as doctors endeavored to treat his lymphatic malformation and the associated problems it caused. At CHLA, he underwent so many surgeries before his ninth birthday that he eventually lost count, estimating the number to be between 60 and 80.

As an adult, Huoh has experienced exacerbations of his lymphatic malformation, which can swell, making it hard for him to breathe, speak and swallow.

“There is fear of mortality,” he says. “But also, there’s always this feeling in the back of your mind of, ‘Why me? Everything else in my life is going so well.’” Huoh says he remembers also having those thoughts as a young boy. “When you’re a child, especially, you don’t want to be different,” he says.

But Huoh was different, and visibly so. As a result, he suffered teasing and bullying, particularly in his first years of elementary school.

While crediting his older brother Michael with helping to end the bullying, Huoh says his own easygoing nature and academic aptitude helped him gain his peers’ respect, significantly reducing bullying incidents after first or second grade.

A Normal Kid

Despite a traumatic start in life, Huoh’s description of his childhood is surprisingly positive.

“It was normal. Very normal,” he says. “My parents treated me like a normal kid. I played soccer and tennis, violin and piano. I ran around with my older brother, went to a normal school. I think the fact that there weren’t different expectations for me was helpful.”

Nevertheless, he still remembers the fear and the separation anxiety he experienced in the hospital.

“I vividly recall being wheeled off to the operating room, crying and scared, asking for my doctor. Sometimes I refused to leave the room until I saw my surgeon.”

That surgeon was Seymour Cohen, one of the forefathers of pediatric otolaryngology and, like the majority of the doctors and surgeons who operated on Huoh, a USC-trained and affiliated physician.

Ever since I was 7 years old, I wanted to be a pediatric otolaryngologist. I even wrote it down in my first-grade story on ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’

Cohen was one of several doctors who inspired Huoh’s childhood ambition to become a physician — and not just any kind of physician. “Since I was 7 years old, I knew I wanted to be a pediatric otolaryngologist,” he says. “I even wrote it down in my first-grade story on ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’”

When it came time to pick a university, there was only one choice: USC. Many of the doctors who operated on Huoh and had become his childhood heroes were on the faculty at Keck School of Medicine of USC or had trained there. In addition, Huoh’s elder brother, Michael Huoh, who graduated from USC Dornsife in 2000 with a degree in kinesiology, was already enrolled in the eight-year baccalaureate medical program there.

“After all, those USC doctors saved my life. I was also fortunate to be awarded a Trustee Scholarship, which meant a free, world-class education,” says Huoh. “So, for me, going to USC was an absolute no-brainer.”

Pattern Recognition

Accepted into the baccalaureate medical program at USC Dornsife, Huoh initially chose biological sciences as his major before switching to psychobiology (now neuroscience), with a minor in art history.

That may seem an unusual choice of minor for someone going into medicine, but Huoh says he still uses the observation and categorization skills he learned in his art history classes at USC Dornsife to help him diagnose his patients today.

“There’s a lot of pattern recognition in art history and that goes for practicing medicine, too,” he says. “Physicians diagnose patients by putting their symptoms and complaints into categories and it’s a very similar mindset to how art historians study paintings.”

Huoh graduated as University Valedictorian in 2003. He credits his USC Dornsife education with making him the physician he is today; his psychobiology major taught him both how to understand people and how best to approach them, he says.

“Knowing why people think the way they do helped me as a physician to understand my patients, but also to understand my own biases and possible flaws in my reasoning.”

He found a developmental psychology course to be particularly useful in helping him to connect with his young patients.

“I’m treating kids from preterm infants to 18-year-olds, so being able to understand what developmental phase children are in, being able to connect and understand their level of comprehension is vitally important. And that’s all stuff I learned at USC Dornsife. Plus, of course, the science — biology, chemistry, organic chemistry, physiology — all those classes I took there obviously laid the groundwork for my scientific ability to be a physician.”

Coming Full Circle

Huoh pursued his medical education at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), where he met his future wife, who now works as an anesthesiologist. The couple married during their residency training at UCSF, and they welcomed their first child while Huoh was serving as chief resident. He later completed his fellowship in pediatric otolaryngology at Stanford University.

For the last 10 years, Huoh has been a pediatric otolaryngologist at Children’s Hospital of Orange County (CHOC), specializing in head and neck tumors. As he puts it, “I do everything above the clavicles and up to the brain, so ear infections, hearing loss, sinusitis, tonsil conditions and pediatric thyroid surgery.”

Earlier this year, Huoh was honored with an invitation to give a grand rounds presentation — a prestigious educational lecture for doctors and medical students — at CHLA’s ear, nose and throat department. It was attended by Dr. Kenneth Geller, former chair of that department and former associate dean and director of the Prehealth Advisement Office at USC Dornsife.

“I had shadowed Dr. Geller when I was a freshman at USC Dornsife, and he was also one of the doctors who treated me when I was a child,” Huoh says. “So, it was really a full-circle moment returning to CHLA as a pediatric otolaryngologist and being invited to give a lecture to the department.”

As a surgeon operating on children with the same condition he had as a child, Huoh is in a unique position to be able to offer families reassurance drawn from his personal experience.

As a result, Huoh has formed particularly close relationships with some of his long-term patients.

Huoh says that what makes him happiest is successfully performing a difficult surgery with a good outcome for the child and their family.

“Being a physician is a hard job,” he says. “We deal with some pretty sick children at times, some very stressful situations sometimes, too, but overall, I feel so fortunate to be able to do this and be able to give back.

“Really, I’m living a dream.”