Sustainability: Human Factors

RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

Effective technology is available to move the needle on sustainability. The challenge is to implement these solutions quickly and at scale.

That’s why USC Dornsife is thinking differently. Our researchers explore how to overcome the economic, political, and psychological challenges that stand in the way of a sustainable future.

Celebrating the Class of 2024

Find everything you need to know about USC Dornsife Commencement Ceremonies on Friday, May 10, 2024.

Get to Know Our Grads

The USC Dornsife Class of 2024 is making their mark. Learn about their aspirations, inspirations and achievements. Read More

In the News

Once Unhoused and Despite a Family Loss, USC Dornsife Senior Graduates and Heads to Yale Law School

Political science major Sophia Perez, fueled by personal experience with housing insecurity, advocates for tenants’ rights.

International Student Graduates with 4 Bachelor’s Degrees from USC Dornsife

Sibo “Carl” Zhou earns degrees in applied mathematics, religion, economics and data science, and global studies, and captures a USC Renaissance Scholar Prize in the process.

40-Something Single Father, Army Vet and Lifelong USC Fan Earns Bachelor’s Degree

Jaime Gomez, who spent six years in the U.S. Army and 16 years in the business world before becoming a first-generation college student, graduates with honors and an undergraduate degree in history.

Laws Requiring Doctors to Report a Dementia Diagnosis to the DMV May Backfire

As the number of drivers 65 and older rises, USC Dornsife researchers investigate for the first time whether state DMV reporting mandates are associated with clinicians’ likelihood of underdiagnosing Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

Curiosity at Work

Stand Out, Together

At USC Dornsife you’ll study the things you love the most. You’ll explore ideas that you’ve never thought about before. You’ll learn how to make sense of the world from all different angles. And, as part of our community, you will help to define a dynamic academic environment focused on improving lives and the world around us.

Meet the Students

USC Dornsife students demonstrate an impressive combination of academic excellence, accomplishment, creativity, and hard work. Each and every student is hand-selected because they bring something special and unique to our community.

A Brighter Future

Isabella Pangilinan Environmental Studies majorUSC Dornsife student Isabella Pangilinan is passionate about finding solutions to some of our world’s most pressing challenges like climate change and social and economic inequity. The multidisciplinary courses offered through her major are preparing her for a career in environmental law.

The Power of “And”

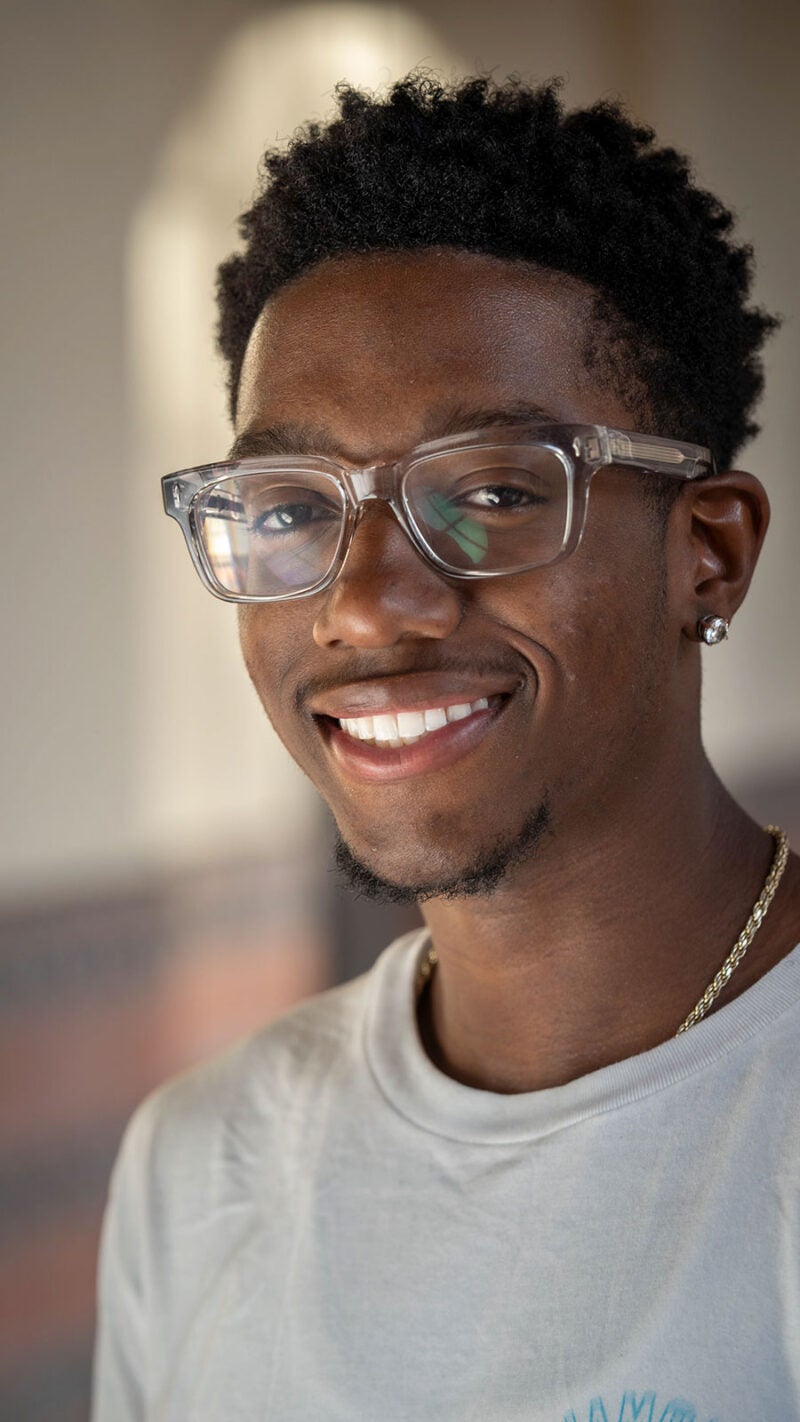

Joshua Senior Biological Sciences major, East Asian Languages and Cultures minorUSC Dornsife student Joshua Senior is studying to become a neurosurgeon. He explains how his liberal arts education at USC Dornsife prepares him for his career goals – and for life.

A Trojan Family Like No Other

Victoria Quon-Chow Human Biology major, Nutrition and Health Promotion minorAs a student at USC Dornsife, Victoria Quon-Chow is bouyed by the support of the Trojan Family as she prepares to become a doctor.

Unprecedented Access to Academic Expertise

Public Exchange fast-tracks collaboration between academic researchers and the public and private sectors to define, analyze, and solve complex problems that organizations face. Through our first-of-kind model, we amplify social impact by making academic expertise more easily accessible than ever before.

“Public Exchange provides the connective tissue that not only identifies appropriate expertise within the university to solve a particular problem, but it takes care of the contracts, project management, and other hurdles that have traditionally made collaboration with researchers challenging.”

Stand Out With Purpose

USC Dornsife’s Public Exchange creates streamlined pathways for public and private sector leaders to tap academic expertise. This model accelerates solutions to challenging social and environmental problems and enhances the social impact of academic research.

@USCDornsife

ICYMI: #USCWrigley Director Joe Árvai moderated the Climate Forward 2024 panel “Climate Change: Are We Prepared?!” with David Livingston – former senior advisor to U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry – and Samantha Bee – comedian, former Daily Show correspondent, and host of Full Frontal with Samantha Bee. The panel discussion centered on topics such as America’s preparedness to have real conversations about climate change and the media’s role in climate change coverage.

To watch the full recorded livestream of Climate Forward 2024, visit the 🔗 in bio.