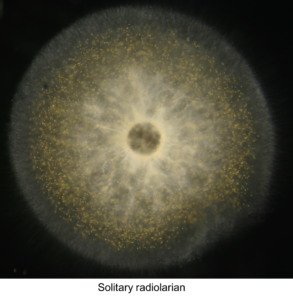

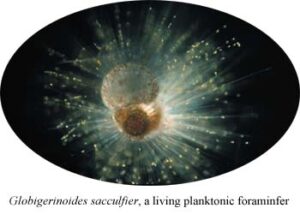

Heterotrophic protists within the taxa Acantharia, Radiolaria and Foraminifera (collectively referred to as “rhizarians”) are among the largest and most complex single-celled organisms in existence. These three groups were once thought to be closely related to much-simpler amoeboid protists (and a few other taxonomic groups) because they share a common feature, the pseudopod, which are cytoplasmic extensions used to engulf prey. However, DNA sequence information has resulted in the reorganization of many of the simpler amoeboid forms into other phylogenetic groups. In addition to DNA sequence differences, the larger rhizaria are also unique in that they produce elaborate, delicate skeletal structures of calcium carbonate (Foraminifera), silica (Radiolaria) or strontium sulfate (Acantharia).

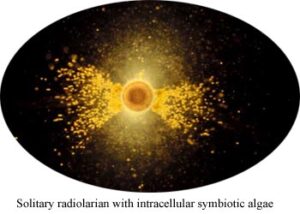

Planktonic rhizarians live almost exclusively in oceanic ecosystems. These species form extensive pseudopodial networks that superficially resemble spiderwebs. These networks are used to subdue prey that are often much larger than the rhizarians themselves. Thus, these species are some of the most voracious predators among single-celled organisms. In addition, most of the surface-dwelling species within these taxa harbor intracellular algae in a mutualistic relationship. These algae contribute to the nutrition of the host, and presumably gain nutrients for growth in return.

Planktonic rhizarians have lengthy life spans, as life spans for protists go (a few weeks to perhaps a year) but these are only estimates as no planktonic rhizarian species has been cultured through successive generations in the laboratory. This fastidious nature, and the fossilizable skeletons that many rhizarians produce, have made many of these species invaluable tools for paleoclimatological studies.

Planktonic rhizarians have lengthy life spans, as life spans for protists go (a few weeks to perhaps a year) but these are only estimates as no planktonic rhizarian species has been cultured through successive generations in the laboratory. This fastidious nature, and the fossilizable skeletons that many rhizarians produce, have made many of these species invaluable tools for paleoclimatological studies.

Our long-term goals in this work include unraveling the enigmatic life histories of these species, establishing their importance in the biogeochemistry of the ocean, bringing these species into laboratory culture for further study, and characterizing the molecular communication responsible for establishing and maintaining the mutualistic relationship between planktonic rhizarians and their symbiotic algae. Communication between algal symbionts and their hosts is a fascinating area of the biology of these protistan species that we have been examining. Chemical communication (and the genetic basis of that communication) appears to be quite species-specific, although little is presently known about the molecular basis for establishing and maintaining these species-species associations.

This work continues as a component of our Current Research Project within the Simons Collaboration on Ocean Processes and Ecology (SCOPE). For more information on SCOPE, click HERE.