TRANSLATIONS OF PASTERNAK’S ”VETER”

Alexander ZHOLKOVSKY (USC, Los Angeles)

M. Jourdain. Je voudrais lui mettre dans un billet: Belle Marquise, vos beaux yeux me font mourir d’amour, mais. .. tournй gentiment.

Maоtre de Philosophie. Mettre que les feux de ses yeux reduisent votre coeur en cendres; que…

M. J. Non…je ne veux que ces seuls paroles-lа ..

M. de Ph. On les peut mettre premiиrernent comme vous avez dit… Ou bien: D’amour mourir me font, belle Marquise, vos beaux yeux .,. Ou bien: Mourir vos beaux yeux, belle Marquise, d’amour me font. Ou bien: . . .

M. J. Mais de toutes ces faзons-lа, laquelle est la meilleure?

M. de Ph. Celle que vous avez dit: Belle Mar quise, vos beaux me font mourir d’amour.

(Molière, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme,II,4)

A successful analysis of a poem is supposed to account for all the relevant patterns in the text and their contribution to the poem’s overall effect. Thus the poetry lost in translation may well be preserved–albeit in a dissected form–in a structural description. In what follows I use theresults of my study of “Veter” (Zholkovsky 1983) in examining several English versions of the poem. In section 1 I outline the deep artistic design ofthe original poem and list its surface manifestations; in section 2, the translationof every surface component is considered plane by plane–in isolationfrom the structure of each version as a whole, which latter is the subject of section 3;the concluding section touches upon the theoretical problem of translatability. the original text of ”Veter,” its literal translation and seven poeticversions are given in the Appendix.

1. The Original

1.1 General design. “Veter” is a masterpiece of Pasternak’s last period,which is known for its Christian wisdom and calm stylistic maturity. themiracle of the speaker’s “life after death” and of his beloved’s consolationby the wind, representing unity with the world, informs the entire poem.

On the figurative plane, the bereaved heroine is unobtrusively compared to the lonely intertextual pine tree (from the Heine-Lermontov classic), while the hero is identified with the wind, through which he speaks from beyond the grave. Generically, the plot is metapoetic: thewind’s lullaby is the archetypal posthumous Text, co-authored by thePoet and the World. Crucial to the poem’s stylistic design (and especially appropriate in a poem about poetry) are its consummate iconicity in theexpression of the central themes by formal means and the delicate balance maintained between opposites.

To mention some of the icons: ‘Death, end, separation’ are reflected in the numerous syntactic stops. ‘Absence’ (as ‘death’ and ‘wind’) has asyntactic counterpart in the consistent use of ellipsis (of the verb raskachivaet “rocks,” implied in lines 4-10), which is echoed by a certain ’emptiness’ on several planes in the middle of the poem. ‘Unity, continuation’ underlie the one period spanning the entire text in a syntactic tour deforce; this effect is mirrored in the rhyme scheme, which has only two main rhymes alternating throughout the poem. Their monotonous alternation is, in turn, an iconic image of a ‘lullaby rocking,’ and that alteration is in evidence also in the poem’s rhythm and sound patterns and very simple and regular syntax (with its bipartitions and alternating parallel constructions).

Together, these icons form an intricate pattern of a slow rocking movement, often flagging and almost coming to a stop, yet always picking up again to continue and form a miraculously united whole. The resulting sense of a ‘quiet miracle of life continuing as if literally in an afterthought’depends very much on the modesty of all the effects, many of which areachieved, as it were, by default: the metaphors (“you—pine tree”; “I — wind”) are only hinted at; the syntactic linking avoids enjambments andsubordinate clauses, relying on regressive conjunction and ellipsis; therhyming is very traditional, even monotonous, ending with the most inconspicuous rhyme (feminine, in e), etc. The phrase structure very gradually develops spiralwise, from minimal subject-predicate sentences to greater complexity, with the maximum reached in the last two lines,which involve an infinitive construction and connectives of purpose (chtob “in order to”; dlia “for”). But even this complexity is within the boundsof parataxis; and it is coupled with semantic, rhythmical and syntactic calm and clarity (‘finding words for a consoling song’; regular word order;syntagms with masculine junctures, etc.), rather than with the sprawling chaos and ecstasy typical of early Pasternak.

1.2 Components. ”Veter”’s deep structural design (outlined above) isrealized on the various textual planes (of rhyme, meter, syntax, etc.) bynumerous features, details, and patterns—the components of the poem’s surface structure. Here is a list of such components, plane by plane (against which the structure of translations may be checked).

Rhymes.

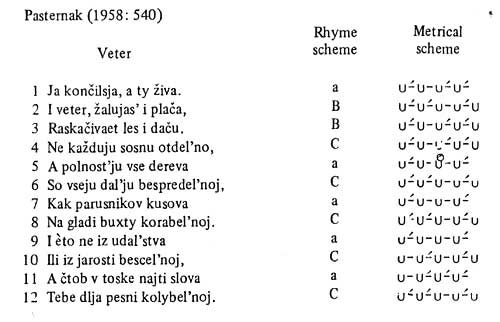

1. The overall scheme is aBBCaCaCaCaC, where:

2. rhymes aC alternate throughout and unite the poem;

3. rhymes 1-3 are similar (in a), with 2, 3 forming a couplet, so thatan intense beginning is opposed to the “lulling” continuation;

4. rhyme 4 appears as “new” and isolated (just like the lonely pinetree in the same line), but it is also the first in the alternating sequence aC, which is to bring unity, order, and a lull;

5. rhyme 5 is the first closure in the aC sequence (in agreement withthe line’s content: “completely all the trees”);

6. rhymes in a and in e alternate, vie for dominance, and the more “average” e wins; the rhyming is in general traditional and exact.

Syntax.

1. In spite of the full-stops in 1, 3, 8, a single period, with conjunctions opening many of the lines, prevails over all the pauses as asort of afterthought;

2. complexity increases from a minimum to a (moderate) maximum,with direct and (later) prepositional objects, adverbs, adjectives,genitive and then comparative and infinitive constructions, twoand then three- or four-place predicates (“the wind to find words for you for a lullaby”) emerging along the way;

3. elements of hypotaxis appear in 2, 3 and resurface in 11, 12, while,due to ellipsis, the middle (lines 5 -10) is verbless.

Line Structure

1. is orderly, regular, without enjambments;

2. binary divisions predominate (0,5 +0,5+2+1+2+2+1+1 +2);

3. the chiasmic lines 2, 3 (NP-VP-VP-NP) form parallel symmetrical A + (B + B) patterns (which agrees well with the intense rhyming and phonetic effects in these lines);

4. lines 5-8 consist of alternating parallel structures A + B – A1 + B1 (“trees” plus “distance” like “hulls” plus “surface”);

5. syntactically they expand the direct objects of lines 3 (two in itssecond half: “forest” and “cottage”) and 4 (one “pine” occupying the whole line) to the length of 2 lines; similarly, lines 9, 10are expansions of the two emotionally negative gerunds in line 2 (“complaining” and “weeping”).

Meter.

1. The poem is in iambic tetrameter, never fully stressed, with two orthree stresses per line predominating;

2. there are fewer stresses in the middle (lines 5-10) than around it;

3. lines with and without stress on the 2nd foot alternate, especiallyin the middle (lines 2,6, 8, 10 vs. 1,3,4,5,7,9);

4. masculine syntagms appear in the beginning (lines 1, 3, 5) andreturn in the end (lines 11, 12), their absence in the middleechoing that on various other levels.

Morphology.

1. The sequence of tenses is Past (in 1)–Present (1-3)–impliedpresent (4-11)–Infinitive connoting Future (11); this “normal”progression helps naturalize the miracle of “afterlife”;

2. the “pine tree” in 4 is in the singular, in accordance with thetheme of loneliness and the corresponding personifying metaphor;

3. the “wind” is also in the singular, which makes its metaphoricalreading possible;

4. the two halves of line 1 begin with the personal pronouns of the1st and 2nd person singular in the Nominative case (Ia “I”– ty “you”), while the last line begins with “you” in the Dative, thusforming a major compositional symmetry.

Phonetics.

1. A chain of paronomasias in t-d-e/a-l’-n connects lines 3 … t lesi dachu–4 otdel’no–6 dal’ju bespredel’noi–8 na gladi–9 udal’stva–2 tebe dlia, creating the thematically important quasi-sememe ‘wide space-distance-physical presence-closeness-unity’;

2. the predominance and alternation of a and e, with a clear tilttowards e in the end, holds true not only for the rhymes but forall stressed vowels;

3. ch/zh + a are frequent in the intense beginning and disappear thereafter;

4. binary repetitions in the stressed syllables are prominent in lines 2 zhal-lach, 3 ach-ach, 5 po-va, 6 dal’-del’, 7 pa-va, 8 bu-be, 12 pe-be.

Lexicon.

1. The vocabulary is simple but dignified, without either colloquialisms or poeticisms;

2. the poem begins with the word konchilsia “ended,” meaning “died,” which creates both a paradoxical effect (the text then ends onthe note of ‘beginning, infancy:’ “cradle”) and that of a somewhatabstract ‘end’ (rather than ‘death’ proper);

3. bukhty korabel’noi “[of the] ship bay” in line 8 is not a regularcollocation, but it is subtly motivated (in the spirit of Pasternak’sdiction) by the expressions korabel’nyi les, lit. “ship-forest,” korabel’naia sosna, lit. “ship, or mast, pine tree,” i.e. “roughspar,” and thus brings together the “forest” and “pine tree” in 2,3 with the “sailboats” and the “bay” in 7; kuzova “hulls” in 7 imply “woodenness” and connote “baskets” (kuzovki), thus linking up with “forest” and “trees” in 3, 5 and foreshadowing the”cradle” in 12.

2. Translations: components

All seven versions clearly strive for accuracy; suffice it to say that,with minor deviations, they match the cognitive meaning of the originalline by line. But it should by now be clear how much of its effect this”artless” poem owes to the poetry of grammar and what challenge it must present to the translator. The poem’s formal patterns are so intimately involved with its message and artistic design that in a sense they are no less essential to a faithful translation than is its cognitive meaning. However, such complete matching is hardly feasible. The reasons for thisare many: various occasional obstacles to the correct understanding ofthe original; systemic dissimilarities of Russian and English; translators’ poetic idiosyncrasies; differences between the two prosodic systems (especially in rhyme and meter). Therefore, while an ideal translation ought to preserve both the deep and surface structure of the original,one can realistically expect at best a faithful reproduction of the deep structural design. As for the surface components, some of them will prove translatable, while others will have to be replaced by alternative manifestations, available in English, of the same deep principle. In thissection, I concentrate on a thorough comparison of the translations with the original, made possible by the description of the poem’s surface structure in section 1.2. Such checking of correspondences, component bycomponent, will lay the groundwork for the generalizations of the next section.

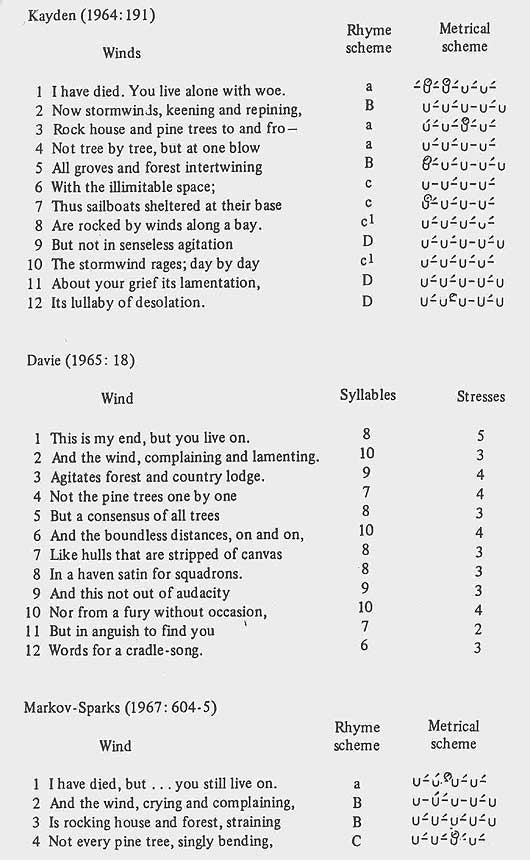

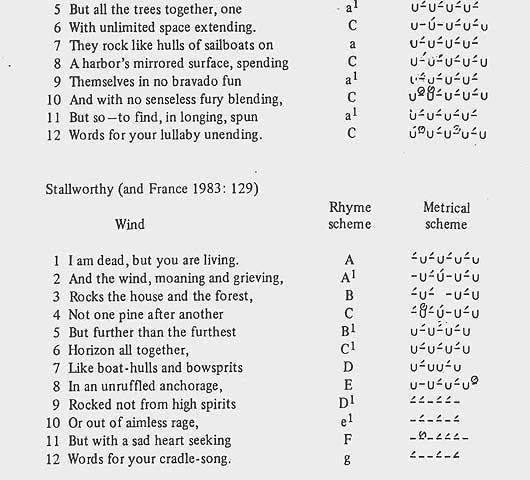

2.1. Rhymes. Four versions (Slater, Markov-Sparks, Kamen, Kayden) arerhymed according to the Romantic convention, with certain deviations in Slater (wide/lie/pride/lullaby), Kayden (base/day), and Kamen (lie/bay?);cf. also the eye-rhyme malignity/lullaby). Because such rhyming is practically dead in modem English prosody, three versions dispose of it:rhymes are completely absent in Guerney, virtually non-existent in Davie (except for a shade of alliteration in the endings of lines 1-4-6-8-10-12) and rely on the consonance of unstressed syllables (reminiscent of W.H. Auden and Yeats) in Stallworthy.

1. Only Markov-Sparks reproduces the rhyme scheme of the original;the other rhymed versions have various schemes of their own (see Appendix).

2. Alternation is regular in Markov-Sparks and to a degree in Kamen (lines 2-5.7-8?-10-12 rhyme), Slater (6, 8, 9, 11), Kayden (who alternates masculine and feminine rhymes) and, to an extent, Davie;Kamen uses masculine rhymes throughout, which weakens alternation. But he conforms to the rules of English prosody (no feminine endings in iambic tetrameter), whereas Slater, Kayden and MarkovSparks, who follow the original, sound unusual to the English ear. As a result, Kamen loses in alternation and thereby in the ‘rocking’ effect, while the three other rhymed versions keep the ‘rocking,’ butcan hardly claim to be ‘lulling.’

3. Repetitions in 1-3 are partially preserved in Slater (the couplet 2-3), Stallworthy (a near couplet 1-2) and Markov-Sparks (the couplet 2-3 plus its similarity with 4-rather than with 1).

4. Isolated rhyme 4 is there only in Markov-Sparks (although somewhat downplayed as a result of its similarity to 2-3) and to a degree in Stallworthy, where a new, four-line alternating sequence of rhymes begins with 3. Conversely, Davie, Kamen and Slater rhyme 4 with 1 (on – one), and in Kayden rhyme 4 is even the closing third member ofa rhyming sequence (1 woe – 3 fro – 4 blow); this, of course, undermines the effect of ‘separateness, isolation.’

5. Rhyme closure in 5 occurs in Markov-Sparks, to a degree in Kamen and in Kayden (where it rhymes with 2, although not as thefirst closure), and still less in Stallworthy. Conversely, in Slater andDavie rhyme 5 is clearly new (instead of 4, where this would fitthematically).

6. Shift from a to e. Tins kind of effect is in evidence in Markov-Sparks (marred somewhat by the lack of opposition between rhymes a and B, on one hand, and C, on the other); in Kamen theshift is roughly similar, while in Stallworthy, a totally new vowel marks the end.

7. New patterns. In changing the rhyme scheme, some of the versions add new symmetries, e.g.: the unity of all rhymes in Markov-Sparks (all nasal); the almost ring-like closure in Slater (-ing in 2, 3 and 10, 12) and Stallworthy (-ng in 1, 2 and 11, 12); the (quasi-) quatrains in Slater and Stallworthy; and an intricate original schemein Kayden, crowned by the final couplet.

2.2. Syntax.

1. Unity is more or less preserved in all versions. It is overemphasizedin Stallworthy (no periods), and very strong in Slater, Kamen, andMarkov-Sparks (one or two periods only). Davie has the three originalfull-stops and all the right connectives, but without the paired rhyming and other rhythmical effects in 2-3, the stop after 3 sounds veryfinal. The absence of “And” at the beginning of Kamen 2 makes thatstop very real too; the same is true of the two full stops (periods in 1,semi-colon in 6) in Kayden. Another source of fragmentation is theappearance of an additional main verb in 7, and that without a connective, in Markov-Sparks, Guern, and Kayden, the latter two alsoadding respectively one and two main verbs in the end of the poem.

2. A gradual increase in complexity occurs in most versions, but itis in part undermined by characteristics (3) and (4).

3. Parataxis/hypotaxis. The accumulation of gerunds in 2-3 is downplayed in Kamen (who has coordinated finite verbs instead) and overplayed in Markov-Sparks and Slater. The final complication is absentin Kayden and Stallworthy, and, conversely, promoted to a subordinate clause in Guerney. The pattern is further marred when gerund/participial constructions and even relative clauses appear also in themiddle, the former in Markov-Sparks (throughout), Slater, Kayden,Kamen, and Stallworthy, the latter in Slater, Guerney, and Davie.

4. Ellipsis is not consistently observed in any of the versions (as aresult of the deviations already noted in (1), (3)), one reason for thisbeing the absence in English of case government, which (namely theAccusative in the direct objects “forest,” “cottage,” “pine tree,” “trees,” “sailboats’ hulls”) helps disambiguate the elliptical construction in the original without repeating the verb “rocks.” The bestapproximations are in Davie (just one extra subordinate clause in 7)and Stallworthy (an extra participial construction in 8). Kayden andGuerney have the greatest number of finite verbs, Markov-Sparks, ahost of gerund constructions. Also, Markov-Sparks and Stallworthylink the final clause (about “finding the words”) with the rockedobject(s), rather than with the “wind,” elliptically implied all along,and thereby undermine the metaphor “I—wind.”

2. 3. Line Structure.

1. Enjambments. Regular lines without enjambments are preservedonly in Guerney’s free-verse translation. Slater and Davie have onerun-on each (in 3 and 11 respectively); Stallworthy has two (in 5 and11), Kayden and Kamen three (in 4, 5, 10 and 5, 7, 11 respectively),while Markov-Sparks is a consistently run-on version. Note that infour versions (Stallworthy, Davie, Markov-Sparks, Kamen) there isan enjambment in 11, the line that comes closest to enjambment inthe original. Kayden’s enjambment in 10 is double: a sentence endsin mid-line, and then a new one starts with a run-on.

2. Binary division (into quarters, halves, wholes and doubles) startsin the original with line 1, whose bisection is preserved in most,versions, except Guerney and Kayden. The regularity of other divisionsis somewhat marred by enjambments (see (1)) and the loss ofsome of the symmetries and alternations (see (3)-(5)) below.

3. Structural symmetries in 2-3 are fully reproduced in Stallworthyand Davie, but not supported by rhyming and sound repetitions; indavie, this and the patterning of line 3 (with the longer term, countrylodge, at the end) makes for a very definite stop after 3 (unlike theoriginal). Several versions (Guerney, Slater, Markov-Sparks, Kayden)keep the pattern A + (B + B) in line 2, but not in 3; Kamen omitsit altogether.

4. Alternation of similarly structured phrases in 5-8 is intact indavie; in Markov-Sparks, it relies on the added run-ons (in 3, 5, 7,8, 11). Stallworthy blurs the pattern in lines 5-6, Slater and Kamenin 8, Guerney and Kayden in 7,8.

5. Expansions of items from line 2 to lines 9-10 and from 3 to 4 to 5-8 are reproduced, faithfully or with variations, in Guerney, Davie,and Markov-Sparks. In Kamen, line 4 has an additional binary division, as have lines 5 in Slater and 7 in Stallworthy. The parallelism of10 with 11 is somewhat blurred in Slater and Kamen. Kayden has twoitems in 5 (”groves and forests” instead of just “trees”) and destroys theexpanding correlation between 2 and 9-10 by shifting the secondnegative emotion (“aimless rage”) to the last two lines (which heturns into a curt, intensely negative couplet, rather than keeping thequiet and broad finale of the original).

2.4. Meter.

1. General rhythm. Four versions, the same that are conventionallyrhymed, follow also the tradition of nineteenth-century Englishmetrics, which gives them an additional archaic ring. Kamen writesin regular English iambic tetrameter (four stresses, eight syllables,masculine clausulas), while Slater, Markov-Sparks and Kayden imitaterussian iambic tetrameter: lines with alternating masculine andfeminine endings, pyrrhic feet and shifts of stress, averaging three tofour stresses per line. Kamen’s meter is somewhat monotonous, butquite normal, while the three others sound unusual, perhapstranslated. Three versions are deliberately modern: Guerney is in free verse (which sounds like plain prose); Davie uses more regular lines whichare between 6 and 10 syllables long (usually 8-9), averaging 3 stressesper line; while Stallworthy writes in accentual (mainly three-fourstress) verse, which at first sounds like conventional trochees (lines 1-4) and iambs (5-6).

2. A “lighter middle” is in evidence in Stallworthy (lines 5-8 averagea little over 2 stresses), whose version is in general the most lightlystressed. Individual light lines in the middle occur in Markov-Sparks (line 6) and Kayden (5,6). Several versions, on the contrary, have thetendency to lighten the final lines: Kayden and Davie (lines 11, 12),Kamen (12), Slater (11). In Guerney and Slater, and probably inmarkov-Sparks, the middle is on the whole even heavier than thebeginning and end.

3. Alternation of rhythms, can be found, if anywhere, in Kayden,where the pyrrhic third foot in 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11 alternates with thestressed one in 1, 3, 7,8,10.12.

4. Ring-like accumulation of masculine syntagms is nowhere in evidence, but another rhythmical pattern seems to compensate for it (as well as for other intensities in 2-3) in some of the versions: a shiftof stress from the strong to the weak syllable, with or withouta resulting spondee, as in Rock house in Kayden 3 and And the wind in Slater 2. This effect occurs more or less consistently in the beginning (Slater 2, 5; Kamen 2; Markov-Sparks 1, 2; Kayden 1, 3; Stallworthy 2), and sometimes also in the end (Kamen, Markov-Sparks 12).

2.5. Morphology.

1. The sequence of tenses (past-present-a kind of future) ispreserved in Kamen, Markov-Sparks and Guerney. Three versions,Slater, Davie, and Stallworthy, start with a present tense (in fact, noneof the seven versions has a genuine past, settling at best for the presentperfect); Kayden ends with a present. Stallworthy keeps all his narrative in the present, thus totally erasing the chronology of the original.

2. The singular “pine tree” is found only in Guerney and MarkovSparks.

3. The singular “wind” is more fortunate: only Kayden has replacedit, in the title and two of the three (!) occurrences, with plurals: winds -stormwinds-winds-stormwind (destroying also the uniqueness andidentity of the original lexeme).

4. Pronominal symmetry is reproduced more or less rigorously inslater (you practically opens the last line) and Guerney (you is thelast word). Others mar the pattern by replacing personal forms withpossessives (Kamen, Davie: my instead of “I”; Markov-Sparks,Kayden, and Stallworthy: your instead of “(for) you”) and/or burying the pronouns in the middle of lines (Davie: my, all three versionswith your).

2.6. Phonetics.

1. Paronomasias and alliterations running through most of the textcan be discerned only in two versions. Slater exhibits two majorchains: w-n/d/t/th (wind whining-one by one-wood-with-wide -weather-when-within-wanton-with words) and f-r-st-r (foreststraining-fir-trees-trees-distance far-stormy-fury-for you),which, separately and in conjunction, come close to matching theoriginal’s quasi-sememe ‘wide space—…—unity.’ The cluster repeated in Davie k-n/ng-t/d-r-s-l (complaining- country lodge-pinetrees-consensus of all trees-stripped of canvas-squadrons-… toccasion-cradle-song) does not yield a clear semantic commondenominator. There are shorter paronomastic-alliterative chains indavie (distances-satin -and this not out of audacity); Kayden (keening and repining-rock… pine trees to and fro-not tree by treeintertwining; agitation-rages day by day; lullaby-about). Stallworthy (forest-after-another-further-together; unruffled anchorage-rocked not from… rage; heart seeking-cradle song); MarkovSparks (themselves in no bravado fun-no senseless fury blending;space extending-sailboats-surface spending-… selves-senseless … . blending-so to .. .-spun); and Kamen (plaintive cry/And rocks;yet in blind malignity); Slater (pride-provide).

2. The overall phonetic picture involves alliterations in one or morelines, but nothing like the clear a – e pattern of the original.

3. Special repetitions in the beginning are most clear in Kayden, withits alliterative chain in 2-3, and Markov-Sparks, with k-r-ing repeated in 2-3; in Slater the common denominator of 2-3 is poorer:the grammatical –ing. In the other versions the alliteration is either notthe same in 2 and 3 or is confined to 2 alone (where it can be quiterich).

4. Binary repetitions are often there, but never prominent enough tocreate the “rocking” effect; cf. Stallworthy 4 one-another, 5 further, 7 boat.. .-bow …, 8 an unruffled anchorage, 11s; MarkovSparks 2 k, 5 t, 6, 8, 11 s(t)-sp; Davie 2 m-l-n-l-m-n, 3, 5,9 f(r);Slater 6, 8 w, 7 s; Kayden 4, 8 d, Guerney 2 k, 12 f.

5. Additional alliteration in individual lines is striking in Davie,Markov-Sparks, Kayden, less so in Slater and Kamen, still less installworthy and Guemey.

2.7. Lexicon.

1. The neutral tone is observed in most versions; none of them everslips into colloquialism. Deviations are rather in the direction of amore elevated style: illimitable, mirrorous, fashion a lullaby (Guerney); malignity (which, moreover, is an eye-rhyme for lullaby,Kamen); lamenting (Davie); illimitable, lamentation (Kayden). In atypically Pastemakian manner, two versions present physical entitiesas abstractions: Davie 5 (consensus of all trees), Stallworthy 8 (unruffled anchorage). A somewhat sentimental note is introduced indavie 8 (satin) and Kamen 12 (soft).

2. Konchilsia “I ended, [menaing] died.” Four versions bluntly say die, dead (Guerney, Markov-Sparks, Kayden, Stallworthy). On thecontrary, Kamen and Davie use (the noun) end, which is closer tothe literal meaning of the original, but lacks its strange quality oflexical collocation as well as its semantic paradox. The best approximation is probably Slater’s I am no more.

3. Kuzova and korabel’noi. The subtle lexical links involved in these words are not preserved or replaced (for instance, in 7 most versionshave “hulls,” which is semantically accurate, but does not specificallyconnote “wood” or “baskets” and “cradle”). Instead, various explanatoryparaphases are offered, e.g. in Slater (sail-less… moored),Kayden (sheltered … rocked… along the bay), Kamen (lie andride at anchor).

2.8. Semantic alterations.

Not only special lexical effects, but practically every lexical-semanticfeature of the original is part of its structure and thus subject to hazards ofinaccurate translation. The alterations range from quite innocuous redistributionof meanings or changes in their relative prominence to moreserious distortions, sometimes justifiable as true to the spirit of Pasternak’spoetry in general if not of this particular poem. The semantic componentsaffected by these alterations come under two major headings.

1. The intensity and impact of the wind are exaggerated in someversions (a very Pastemakian tendency). The wind’s sheer ‘force’ isheightened in Slater 7 (stormy weather) and Kayden 2, 10 (stormwinds, stormwind rages). These two versions also increase the ‘number’ of objects/nouns rocked by the wind in line 5 (Kayden grovesand forests; Slater whole wood, all trees); Davie achieves the numericalincrease with a typically Pastemakian plural (6 boundless distances); Stallworthy decreases the number (no “trees” in 5), butcompensates by doubling the “hulls” in 7 (boat-hulls and bowsprits). The ‘rocking effect’ of the wind is amplified in Slater 3 (straining),Markov-Sparks 3, 4, 8 (straining, bending, spending), Kamen 5 (waving high), Kayden 3 (to and fro). Two versions, very Pasternak-like,intensify the ‘contact’ between the participants: Kayden 5 (intertwining), Kamen 6 (high into and with). Finally, the ‘duration’of the wind (and lullaby) is prolonged in Kayden 11 (rages day byday) and Markov-Sparks 12 (unending).

On the whole, the wind’s intensity is rather overplayed in Kayden,Slater, and Markov-Sparks.

2. The balance of grief/consolation is sometimes tipped due to thisintensification of wind and also to the following. The ‘human grieving’ in the beginning, implied and metaphorized in the original, isspelled out in Kayden 1 (woe) and made more prominent by itsaccumulation in the closing lines and even words: Slater 12 (grief andlonging), Kayden 11, 12 (grief… – lamentation … desolation). Some versions lose the motif of ‘finding [the words],’ with its connotations of an ‘orderly intellectual activity:’ Kamen, Slater, Kayden,and, to a degree, Stallworthy (who has seeking).

On the whole, Kayden and perhaps Slater come out as too ‘sadand chaotic’ versions.

3. Translations: wholes

I will use the findings of § 3 to characterize as wholes first the entireset of translations and then the individual versions one by one.

3.1. A composite portrait of the seven “Winds.” To be sure, such a portrait is problematic, mainly because the natural variety of renderings isfurther compounded here by the split into the traditional and modernversions. Four translations achieve prosodic closeness to the original,with its ‘musicality,’ ‘rocking’ etc., at the price of modernity, and sometimes even the exactness of copying proves imaginary, as with the alternation of masculine and feminine rhymes, which sounds ‘unusual’ rather than ‘lulling.’ On the other hand, the deliberately modern versions do indeed lack much of the original’s musicality, so important in a cradlesong. And yet, as we focus on translations as wholes and on their deep structural principles (rather than on the individual surface components of separate planes through which these principles are realized), it becomes possible to make generalizations about all seven translations.

1. ‘Regularity and moderation’ are on the average well preserved,with deviations in both directions: some versions tend toward stronger impetus (Markov-Sparks, Kamen. Slater), while others achieve calm at the expense of musicality (Guemey, Davie) or weighty substance (Stallworthy).

2. The ‘(flagging) unity’ of the original is reproduced faithfully enough, by some means or other, in most versions, probably with Stallworthy topping the list.

3. ‘Rocking alternation, binarity’ has been less fortunate; still,Slater, Markov-Sparks, and Stallworthy do convey this idea.

4. ‘Spiral development,’ with an intense beginning, a wide butempty middle, and a complex but quiet and clear ending, has provedvery hard to render in full. Either the beginning is not sufficientlyintense (Davie, Kamen, Kayden, Guerney), and/or the middle is notempty enough (Slater, Davie, Markov-Sparks, Kayden), and/or theend lacks in complexity and material substance (Slater, Kayden,Davie; to an extent, Stallworthy) or calmness (Markov-Sparks). Allin all, Stallworthy comes closest to the original in this respect.

5. “Special effects.” Of these, the intensity of the beginning hasfared quite well (except for Guerney and probably Kamen); the “Iwind” link is lost only in Kayden; the loneliness of the pine tree ispreserved only in Markov-Sparks (and maybe Guerney); the progression of tenses and the pronominal frame are rendered more or lessaccurately only in Slater and Guerney; while the subtle effects like in konchilsia, kuzova and korabel’noi remain virtually untranslated.

To sum up, the translations give, on the whole and average, an adequateidea of the deep design of Veter, but fail, predictably, to reproducethe wealth of surface manifestations of this design. As a result, none ofthe “Winds” achieves that harmony of force and lightness, musicality andprofundity, art and artlessness, which make “Veter” such a perfect expressionof its theme.

Turning now to individual versions, I briefly concentrate on threetypes of correspondence: reproduction of original patterns, deviation from them, and compensatory transposition of patterns onto other planes. I also note that the translated versions, functioning as systemic wholes,tend to display consistent structural modifications of the structure, discernible behind individual inaccuracies and attributable to the interactionof that structure with the idiosyncratic stylistic preferences of thetranslator-poet, his or her reading of the poem, etc. In the analysis of eachversion, before discussing the degree of its correspondence to the original,I try to identify its major modificational tendency.

3.2. Guerney. This free verse rendition is probably the least successful. Deliberately foregoing the advantages of traditional prosody, it also doesnot avail itself of the opportunities offered by free verse to faithfullyreproduce the linguistic shape of the original.

1. Well-preserved are: (a) the semantic content; (b) articulationinto lines, (c) the singular of the pine tree in 4.

2. The most obvious losses involve (a) ellipsis (especially in lines 7-9); (b)the binary division of lines (especially 1, 3, 12) and theirrelative length; and a variety of other compositional and musicaleffects.

3. There are no interesting compensations, except for the painstakinglyaccurate and literal, at times explanatory, translation of thepoem’s cognitive content.

3.3. Markov-Sparks. This translation is at the opposite pole of theprosodic scale. It is the most traditionally musical imitation of “Veter,” perhapseven more intense and at the same time more monotonously lulling thanthe original—with the exception of the strange sound resulting from theuse of feminine rhymes.

1. It is remarkable for the preservation of (a) the elaborate rhymescheme, including (b) the phonetic shift (to e); (c)the lonelinessof the pine tree, and (d) the consistent alliteration (in allthe rhymes and in individual lines).

2. The deviations undermine: (a) the effects of ellipsis and ’emptyingof the middle:’ instead, the verb “rock” is spelled out anew in 7,and the middle is filled with numerous verb forms (the participles in 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12); (b) the single thread linking the wind in 2 withthe ‘word-finding’ in 11, 12: the subject of to find is either they, i.e. ‘all the rocked objects’ or just the hulls; (c) the regularity of lines without enjambments (on the other hand, such regularity might soundtoo traditional); (d) the clear opposition of rhymes B and C, especiallyimportant at the juncture of lines 3 and 4, where it emphasizes theisolation of the pine tree.

3. The major transpositions replace: (a) the syntactic unity due toellipsis – with the phonetic (nasal) unity of all rhymes and the rhythmical unity due to run-ons; (b) the alternation of regular lines without run-ons – with the alternation of run-ons (in 3, 5,7,8, 11) and ofparticiple forms (in 4, 6, 8, 10, 12); also (c) the metrical (pyrrhic)lightness of lines 6, 9 compensates somewhat for the lack of ’emptiness’in the middle on other planes.

3.4. Slater. This is another purportedly exact prosodic copy of the original. Like Markov-Sparks, it is clearly on the intense side, but without theformer’s monotony.

1. Slater preserves well (a) the unity of the period in its variousmanifestations (syntax, paronomasias, and, to a certain extent,rhyming); (b) the intensity of the beginning; (c) the alternatingprinciple.

2. Among the losses are (a) the lightness of the middle; (b) therhyme scheme, with its effect of overall unity and of the pine tree’sloneliness; (c) the calming down in the end (in 9,10,12).

3. An interesting compensatory effect is the transposition of thering-like symmetry of the beginning and end from the metrical plane (masculine syntagms) to that of rhyming (-ing rhymes in 2, 3 and10, 12).

3.5. Kamen. Kamen’s version is quite traditional and “correct” metrically (without the strange alternation of masculine and feminine clausulas) andless so in rhyming (on/one; round fbeyond; lie/bay; malignity/lullaby). Onthe whole, it sounds somewhat uninspiredly monotonous.

1. It rendets fairly well (a) the sense of unity in its various manifestations (except in the beginning) and (b) the effect of a phoneticshift, although not exactly in the same direction as in the original: here it goes open rhymes in u: and ai.

2. The major losses concern (a) syntactic regularity; (b) the intensityof the beginning; (c) the emptiness of the middle; and (d) the loneliness in line 4.

3. As far as compensations go, (a) the lack of alternation in the typeof rhymes (all masculine) and in the syntactic and rhythmical structureof lines is partly made up for by the alternation of rhymes, especiallythose in ai; (b) note also the idiomatically English structure wavinghigh into and with the vast beyond: although used at the expense ofthe syntactic patterning, regularity, and restraint of the original, itprobably is what (an early) Pasternak would have liked to tap inenglish syntax.

3.6. Kayden. This version, traditional prosodically, is a radical reworkingof the original: the overall effect is rather cosmic-meditative than lyrical;the stormwinds are unrelentingly strong and negative throughout thepoem; the clear division is in two halves (rather than three thirds) with athematic shift from a mere chaos to one interpreted in human terms asdesolation.

1. Kayden does have (a) a phonetic shift (from ou and ai to ei, whichbisects the poem); (b) he maintains the intensity of the beginning (including a rich paronomasia repining – pine trees) and its distinctionfrom the rest of the poem; and (c)even adds the Pastemakian motifof ‘intertwining.’

2. Yet, completely lost are the effects of (a) alternation, and (b)ellipsis; and (c) all metaphorical links between “I” and “wind” andbetween “you” and the “pine tree.”

3. The compensations are closely connected with the modifications.

(a) Unity, undermined by the absence of ellipsis, the many syntacticstops and the discontinuity in rhyming, is partly made up for by theinternal unity of each of the two halves of the text. (b) For the effectof the ’empty middle’ this version substitutes the symmetrical bisection, implemented by: a syntactic stop (after 6); a phonetic shift (to e in the rhymes after 5); an exact sub-rhyme (space–base, in 6, 7);a short syntactically separate distich (7-8). (c) The final complicationcum-clarity is replaced with a curt, somewhat Victorian final couplet. (d) The peculiar rhyme scheme of “Veter”is matched by a no less intricate patchwork of double and triple rhymes, which involve: correspondences like space, base/bay, day; tentative couplets (in 3-4; 6-7;11-12); and a tentative overall mirror-symmetry (five-line stanza of3+2 rhymes), supported by the general bisection of the text. (e) theexaggeration of the wind’s force and of the lullaby’s sadness is toneddown by the rhythmical lightness of the final couplet and the syntactic fragmentation of the second half of the text.

3.7. Stallworthy. This is a modern and yet quite musical rendition of the original, somewhat on the gentle side, more a rustling breeze than astormwind.

1. Well–preserved are (a) ellipsis and (b) unity in many aspects,including syntax and alliteration; (c) the intense beginning and (d)empty middle, and (e) binary division and repetitions in many of thelines.

2. Among the losses are (a) the rocking alternation of lines; (b) theloneliness of the pine tree; and (c) the sequence of tenses (the poemis all in the present).

3. Interesting compensations concern: (a) the symmetry of the -ng rhymes in 1, 2 and 11, 12, which replaces some other ring-like symmetries of the original; (b) the distinctly different final rhyme (song),which embodies the emergence of ‘something new’ in the end (expressed in the original by lexical and syntactic means: the verb “to find” and the relative complexity of the concluding lines);(c) the peculiar rhyming pattern and rhyme quality, both unobtrusiveand original, which replace the intricate traditional rhyme scheme of‘’Veter.’’

3.8. Davie. Davie offers perhaps the most prosodically modern and independent version within the limits of (quasi-) rhymed verse.

1. This translation preserves (a) the richly alliterative and paronomasticcharacter of the original; and (b) the principle of alternation mainly in rhyming, although it suggests a ‘thread of conceptual unity’rather than a ‘lulling rocking,’ based as it is on a very subtle alliterationnot supported by such musical means as meter and syntax; (c) arelatively intense beginning and; (d) relatively complex unity ofthe end (somewhat undermined by rhythmical lightness).

2. The major losses are (a) the unity of the period (too many stopsand two few recurrent rhymes); (b) the ring-like symmetry of thebeginning and end; (c) the loneliness of the pine tree.

3. The compensatory–modificatory tendencies involve (a) the shiftfrom a serious yet charmingly musical lullaby to a profoundly sober,cerebral and somewhat lofty philosophical meditation, manifested by(a) the subtlety of alliterative rhyming; (b) choice of words (lamenting,consensus, audacity) and of some grammatical categories (boundless distances in the plural), quite in the spirit of the Pasternak diction.

4. On translatability

My conclusions are hardly unexpected. I believe I have succeeded inshowing that a thorough thematic-expressive description of the originaldoes provide a useful frame of reference, a grid of structural coordinates,against which to test translations. In my opinion, such a description is anindispensable tool for the practicing translator. Judging by the sevenrenditions of “Veter,” adequate translation is not impossible—if not indetails, at least in major outlines. Predictably, the deep design lendsitself to reproduction better than the surface structure. This is, of course,due to the formidable odds of the translating project: the original structurehas to be superimposed on a different linguistic medium (the Englishlanguage), a different prosodic system (of English verse) and, more specifically, a different set of stylistic conventions (of modem Anglo-Americanpoetry writing), to say nothing of the poetic personality of the translator-poet.

As a result, the translations at best give their readers a good idea ofthe kind of poetic experience the original produces in the native readers but fail to enact and enforce the experience itself. It appears then that inorder to recapture the spirit of the original text convincingly, the translator must hold on to its letter. This might come as a surprise, becausethroughout this article I have insisted on preserving the structure – not thematerial shape, the underlying deep principles – not the specific surfacecomponents, patterns, and details of the original. But it turns out that asufficiently rich and elaborate surface structure, although remaining aconstruct (=an abstraction), does define a unique textual realization (hence the epigraph).

All of this does not mean that successful translation is unfeasible. Itmay materialize – but as a fortunate coincidence, rather than as an assuredsystematic correspondence.

NOTE

1. In writing this article I profited much from discussion with and advice ofVladimir Markov, Olga Matich, Judson Rosengrant, Marjorie Perloff and Nicholas Warner, to all of whom I extend my gratitude.

REFERENCES

Davie, Donald. The poems of Dr. Zhivago. New York: Bames and Noble, 1965.

Kamen, Henry. Boris Pasternak. In the interlude: Poems 1945-60. London: Oxford University Press, 1962.

Kayden, Eugene M. Boris Pasternak. Poems. Yellow Springs, Ohio: The Antiochpress, 1964.

Markov, Vladimir and Merrill Sparks. Modem Russian Poetry. An anthology withverse translations. New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967.

Pasternak, Boris. Doktor Zhivago. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1958.

Pasternak, Boris. Doctor Zhivago (“The Poems of Yurii Zhivago,” translated by bernard Guilbert Guerney). New York: Pantheon, 1959.

Pasternak-Slater, Lydia. Pasternak. Fifty poems. London: Alien & Unwin, 1963.

Stallworthy, Jon and Peter France. Pasternak. Selected poems. New York/London: W.W. Norton, 1983.

Zholkovskii, A.K. “Poezija i grammatika pasternakovskogo ‘Vetra.’” Russian literature, XIV, 241-286.

APPENDIX

Literal translation (Zholkovsky)

Wind

Guerney (in Pasternak 1959: 439)

Wind

1 I have died, but you are still among the living.

2 And the wind, keening and complaining,

3 Makes the country house and the forest rock—

4 Not each pine by itself

5 But all the trees as one,

6 Together with the illimitable distance;

7 It makes them rock as the hulls of sailboats

8 Rock on the mirrorous waters of a boat-basin.

9 And this the wind does not out of bravado

10 Or in a senseless rage,

11 But so that in its desolation

12 It may find words to fashion a lullaby for you.