Vietnamese Horror Story

As the first hypnotic notes of The Doors’ “The End” played over a lush, idyllic Vietnamese jungle, 10-year-old Viet Thanh Nguyen’s eyes widened as the peaceful green palm trees erupted into a fiery, orange inferno. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, the young boy watched, mesmerized, taking in the drifting smoke and the rhythmic chopping sound of the United States military helicopters silhouetted against the hellish scene of destruction unfolding on the TV screen in his family’s cozy California home.

It was 1981, and unbeknownst to his parents — refugees from Vietnam who fled to the U.S. six years earlier with their then 4-year-old son when Saigon fell to the communists — Nguyen had rented Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam War epic Apocalypse Now to while away a solitary weekend while his mom and dad worked long hours at their neighborhood grocery store in San Jose. Watching it changed the 10 year old’s destiny, setting him on the path to becoming a USC Dornsife professor and a Pulitzer Prize–winning author.

“The World War II movies I’d watched weren’t horrific, and it was clear who was the good guy and who was the bad guy,” said Nguyen, Aerol Arnold Chair of English and associate professor of English and American studies and ethnicity. “Here that wasn’t clear to me, and what was worse, people like me were the ones being killed. My 10-year-old mind had no way to make sense of drugs, psychedelic rock, murder, atrocity, massacre and Playboy bunnies. It was a war movie that was horrific, and that placed me at the center of that horror. I was confused because I wasn’t sure whether I should be rooting for the Americans who were doing the killing, who were committing all the horrors, or whether I should be identifying with the Vietnamese who had the horror being inflicted upon them and their voices taken away.”

For the young Vietnamese-American boy, watching Apocalypse Now opened the door onto a very different view of a very different war, one that was to have major personal and professional repercussions.

“Watching that film made me feel like there was no place for me in American culture,” he said.

It was only later, after he developed a political conscience at college, that fury also entered the picture.

“Looking back, I realized that rage had rendered it impossible for me to be an American. It made me feel like an outsider, and I knew that anger was going to be a catalyst for me to try to make sense out of the movie, the Vietnam War, and my place both in American society and in the history of that war.”

A Question of Perspective

Twenty years later, that anger was the catalyst that drove Nguyen to write his Pulitzer Prize–winning first novel, The Sympathizer (Grove Press, 2015), which explores the Vietnam War from multiple perspectives through the lens of his conflicted protagonist, an American-educated spy for the Viet Cong.

An American soldier guides U.S. Army helicopters in to land through a haze of purple smoke. Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images.

“Although a huge amount of work had already been done about the Vietnam War, I felt that no one had yet tried to write a novel that dealt with all sides, and with the problem of looking at a war from all sides,” Nguyen said. “That was going to be my subject, not just the war itself, but how the war was regarded.”

The question of perspective lies at the heart of Nguyen’s novel and is a vital one for anyone seeking to establish a more balanced, less-biased truth about the 20-year conflict. As his protagonist puts it: “This was the first war where the losers would write history instead of the victors.” For not only America’s understanding of the Vietnam War but the world’s perception of the conflict has been shaped almost exclusively by the viewpoints of Americans — by American soldiers, politicians and journalists, and by the makers of American culture — while Vietnamese perception of the most deadly combat in its history has largely been ignored.

For Nguyen, winning the Pulitzer was a personal victory, a validation of his long-term project to force Americans and Vietnamese to reconsider the history of the war and their involvement in it.

“Winning the Pulitzer felt like an endorsement of the importance of the memory of this war and of seeing it from another perspective,” he said. “I think it’s a vindication of the idea that the Vietnam War remains very much in the American consciousness.”

Americans are still arguing about the Vietnam War, and the arguments today have changed very little from those that raged when the conflict was in full swing: Was it a good or a bad war? Was it a war of racism and atrocity, or a war of noble, failed intentions?

While Nguyen says the U.S. is not unique in the way it remembers and forgets its wars and those involved in them, it has nevertheless focused on the Vietnam War almost exclusively as an American war in terms of its cost — to American lives and unity, and with respect to damage to the American psyche.

This, he argues, is illustrated in presidential speeches, from President Jimmy Carter in the 1970s to President Barack Obama today. Carter described the Vietnam War as one “of mutual destruction.” While no one denies the tragedy of the 58,000 American dead, that figure pales next to the 6 million Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians who died during the war and its aftermath. Obama’s 2012 speech commemorating the 50th anniversary of the war continued to focus squarely on American soldiers with virtually no mention of Vietnamese fatalities. It also went a step further, explicitly describing the war as one of “noble sacrifice” — a perspective on the war that has also found favor among Republicans.

“The bipartisan recasting of American memory is not simply to focus on American soldiers,” Nguyen argues, “but to turn the memory of what was at best an ambivalent war for Americans into one that is now a war of noble intentions and human failure, rather than one of atrocity and racism as it was portrayed by the anti-war movement in the 1960s and 1970s.”

Brig. Gen. Viet Luong also takes issue with this effort to rewrite history. The alumnus, who earned a degree in biological sciences in 1987, is the first Vietnamese-born general officer in the U.S. military.

“It’s very difficult for me to view the Vietnam War as anything other than an ugly conflict that should never have occurred,” Luong said. “So it’s very hard to recast it as a noble struggle between people with different ideologies because there was nothing noble about that war.”

Bravery and Sacrifice

Luong was 9 years old when he escaped the ravages of war-torn Vietnam with his family, just a day before Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese on April 30, 1975.

Communist forces had already started shelling the airport when U.S. marines flew Luong, his father — an officer in the South Vietnamese marine corps — mother and seven sisters to a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, the USS Hancock. From there, Luong and his family, along with thousands of other Vietnamese refugees in danger of communist reprisals, made their way to the U.S. under Operation Frequent Wind, a political asylum program.

“We barely escaped,” Luong said. “My sisters and I were scared to death. I still remember the formation of marine helicopters coming in to rescue us. They appeared, like images of angels from the sky.”

When they landed on the USS Hancock the ship was so big, Luong remembers, that he and his siblings were disoriented.

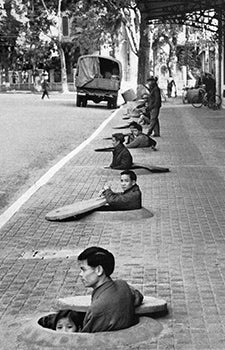

The cover of Life magazine from April 7, 1967, featured Hanoi residents taking shelter underground during an air raid. The headline reads “First American Photograph in North Vietnam Under Siege.” Photo by Lee Lockwood/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images.

“We asked our father ‘Dad, where are we?’ He said ‘We’re on a U.S. carrier.’ We said ‘What does that mean?’ And he replied, ‘It means nothing in the world can harm you now.’”

Standing on the deck of the Hancock, Luong said, he already knew he would serve in the U.S. military to give back to the nation that had saved him and his family from almost certain death. Thirty-nine years later, he pinned on his first star as he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general.

While Luong condemns the war, he pays tribute to the bravery and sacrifice of the American soldiers who fought in Vietnam.

“They did a super job,” he said. “You can’t take anything away from those men and women who fought over there. It took a little time, but I think we’ve recovered from Vietnam and that, demonstrably, our men and women across the armed forces have done a great job in the last decade or more of war.”

Nguyen, however, believes that the scars left by Vietnam, both in America’s psyche and on its soul, have yet to heal.

Before Vietnam, he argues, the U.S. saw itself as a world benefactor, a strong country that had never lost a war.

“The aftermath of the Vietnam War meant that no longer could Americans be self-confident about either their military prowess or their good intentions,” said Nguyen, describing the conflict as “deeply divisive.”

“I think of it as a civil war in the American soul,” he said. “American self-confidence still hasn’t been restored to the quality it had in the 1950s. The long shadow of the Vietnam War continues to hang over every American foreign policy venture, even today.”

A Lesson in Democratic Thinking

Although their childhoods and backgrounds could not have been more different, Thomas Gustafson, associate professor of English and American studies and ethnicity, shares with Nguyen a youth so profoundly impregnated by the Vietnam War that he, too, cites the conflict as the greatest influence in shaping his scholarship.

Raised at the dead end of a dirt road in a small, conservative town in New Jersey, Gustafson first became aware that there was more than one perspective on the Vietnam War during his hometown’s Fourth of July parade.

It was 1967 and Gustafson was 13 years old.

“Amid all the Americana, high school students just a few years older than me were carrying a coffin in the parade to protest the Vietnam War. When the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ played they sat down,” Gustafson recalled. “My baseball coach, who was also chief of the fire department, made them stand and respect the flag. His politics were different from mine, but I knew he had a nephew who’d been killed in Vietnam. I felt sympathetic to the high school protestors, but I could also see the war from the point of view of this wonderful man who had lost his nephew.”

The rift Gustafson felt within himself that day was an echo, he realized, of the division he now knew existed within his country.

Gustafson, who is writing a memoir about the events of that parade, said growing up during the Vietnam War gave him his first lesson in what he calls “democratic thinking.”

“Tyranny tells people to learn from or respect one voice,” he said. “Democratic thinking teaches you to see things from multiple perspectives, to trust no single point of view.”

At university, his first politics course had him reading the Pentagon Papers. “I was completely shaped by responding to Vietnam and it still affects how I teach today,” he said.

Just as Nguyen’s world was turned upside down by watching Apocalypse Now, Gustafson experienced a cataclysmic awakening when, as a junior at Yale University in 1974, he saw the anti-war documentary Hearts and Minds, which affected him so much emotionally he couldn’t sleep at night.

“I was struck by Gen. William Westmoreland’s statements in the documentary that ‘Orientals’ don’t have the same respect for life as Americans. His words are juxtaposed with a funeral in South Vietnam showing a mother, ravaged with grief, throwing herself on a grave,” Gustafson said. “That Westmoreland, the leader of this war, is engaging in this dehumanization, this prejudice and stereotyping of ‘Orientals,’ shows that either he doesn’t understand anything about Asian culture, or that he is engaging in this dehumanization as propaganda or because it allows him to conduct the war.”

Gustafson still shows the documentary to his students at the end of his American studies class “America, the Frontier, and the New West.”

“I don’t want there to be any softening of the horror,” he said.

The birth of his oldest daughter in 1983 added another perspective — one of empathy.

“When I saw parents visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., I imagined what it would be like to lose a child, and I broke down and cried. As a literature professor, I teach critical thinking, but it must be supplemented by empathy, the ability to put ourselves in the shoes, the souls, hearts and minds of someone different from ourselves. For me, the seed of that came from Vietnam.”

Gustafson, who is fascinated by the politics of memory and whose research focuses on the power of political language and discourse to shape those memories, agrees with Nguyen that those who are pushing to rewrite the Vietnam War as a war of noble failed intentions are winning.

“We’re such a militaristic country, but we shy away from that, preferring instead to see ourselves as a republic, not as an empire,” he said. “We want to cover up how we began and developed as an empire. And now we’re covering up Vietnam.”

The Wrong War

A well-meaning American soldier from the 7th Marine Regiment tries to comfort a distraught Vietnamese child by giving her a doll, near Cape Batangan, Vietnam, 1965. Photo by Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images.

“Covering up” is not a new concept where Vietnam is concerned, argues Steven Ross, professor of history and director of the Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life at USC Dornsife. While President Lyndon Johnson’s government maintained the official line, telling Americans that Vietnam was about saving democracy — that if Vietnam fell to communism, everything else would fall — it knew this to be untrue, Ross said.

In fact, he added, according to a secret CIA memo, 70 percent of America’s reason for fighting the Vietnam War was a face-saving exercise to avoid a humiliating defeat to the U.S. reputation as a guarantor.

“Only 20 percent was to keep South Vietnam from falling into Red Chinese hands, while 10 percent of our war aims were committed to helping the South Vietnamese enjoy a better, freer democratic way of life,” he said.

When such memos were revealed, the result, Ross said, was that Vietnam killed Americans’ confidence in the ability of American military power to fight the right wars. “Vietnam was the wrong war at the wrong time in the wrong place.”

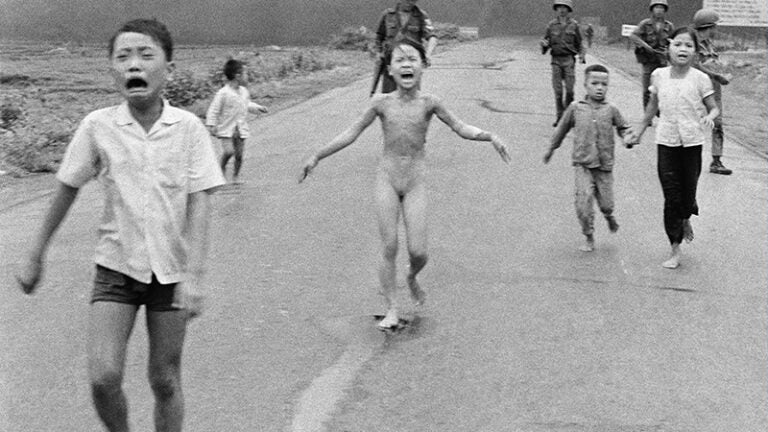

For many, the horrors of the Vietnam War were — and still are — unforgettably distilled in one unbearable image: that of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the 9-year-old Vietnamese girl running naked in the collective eternity of our imaginations down a road, wailing in agony. She is naked because she tore off her burning clothes after a South Vietnamese napalm bomb attack on her village on June 8, 1972. The photograph, which became emblematic of the anti-war movement, dominated the front pages of the American press. In it, the callous cruelty of war is stripped bare and the viewer is forced to confront America’s complicity in committing atrocities against the innocent.

Today, despite our perception that we are more knowledgeable about current events thanks to 24/7 internet news access, Nguyen says censorship of war-zone images has increased, leaving us paradoxically sometimes less well informed than we were during the Vietnam era.

Ross agrees, noting that footage similar to that showing military coffins being unloaded from troop ships, which appeared on the nightly news during the Vietnam War and helped sway public opinion against the war, was banned by President George H. W. Bush — a ban that endured for 18 years during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

“Censorship is much more pervasive now so the media simply doesn’t have access to U.S. military operations in the same way American and foreign media did in Vietnam,” Nguyen said. “This means the possibility of capturing and seeing horrific images like the napalm girl, which played a role in bringing American involvement in the Vietnam War to an end, is now reduced for the U.S. population.”

Reduced Impact

Even when such images do emerge, their impact is diminished, Nguyen said.

“When that image of Kim Phuc came out it was 1972. America hadn’t seen images like that before, so it had tremendous shock value. I was 10 to 15 years old when I first saw these types of images, and they were devastating for me. One I particularly remember showed a woman weeping over the remains of her husband that were in a small garbage bag.”

Nguyen argues that the impact of such images is now reduced due to the desensitization caused by the rise in terrorism and our exposure to widespread graphic imagery in movies, video games and terrorist videos.

“These images are simply not as raw and shocking to us as they might have been to people 40 or 50 years ago,” he said.

If we maintain that the photograph of Kim Phuc resonated so deeply on so many levels that it had an impact on policy and indeed hastened the end of the war, what can we say about a more recent shocking photograph of another child tragically caught up in the consequences of war — that of Alan Kurdi, the 3-year-old Syrian refugee boy washed up on a Turkish beach in September 2015?

Although the Kurdi image went viral, it did not have the impact of the napalm girl in mobilizing people and governments to find a solution to the refugee crisis, or to end the conflict that is causing such suffering, argues Sarah Gualtieri, associate professor of American studies and ethnicity, history and Middle East studies.

“There were platitudes about caring for people in crisis, but the Kurdi image had limited resonance in American policy debates, despite the fact that it circulated so widely in the U.S.,” she said.

“Images of children resonate very deeply with us. Children symbolically represent innocence, and we share a global ethic of caring for them. The image of the napalm girl fleeing in terror, the way she is robbed of her innocence in that moment, captured the deplorable longstanding involvement of the U.S. military in the region.”

But the Kurdi photograph, although equally heartbreaking, is more complicated. It’s only a matter of time, Gualtieri notes, before the sympathy it evokes is overshadowed by more recurrent and powerful images of terrorists.

Uneasy Listening

Nguyen and Gustafson think that while these images of children caught in war can still have an impact, the possibility of them moving us to take action has been reduced.

“What we learned from Vietnam is not to show pictures of war,” Gustafson said. “Our media is not as willing to show the ugly, tragic, atrocious side of war. We try to learn some wisdom from the suffering caused by the tragedies of history. But in some ways we don’t want to learn; we don’t want to confront it. We have such trouble seeing the ugly sides of America. There’s easy listening and uneasy listening, and we have the hardest time doing the uneasy listening to the voices that don’t flatter us, that don’t self-justify us. But that’s what we do in the humanities. We try to get students to listen to those voices, even when it’s challenging.”

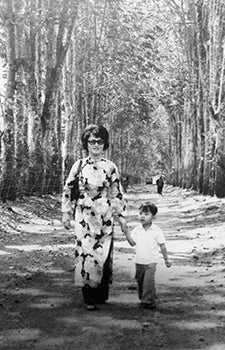

Viet Thanh Nguyen as a small child in Vietnam with his mother, Linda Kim Nguyen, at a rubber plantation in Ban Me Thuot in 1973. Photo courtesy of Viet Thanh Nguyen.

Luong first saw Apocalypse Now in his late teens. Unlike Nguyen, it had little effect on him. “To me it was just another movie, it didn’t have an impact on me either way,” he said.

However, like Gustafson, he says he has been deeply moved by some of the documentaries made about Vietnam. He cites Last Days of Saigon and certain combat documentaries. As an American soldier and a former Vietnamese refugee, seeing images of the war triggered conflicting emotions.

“They made me feel absolutely torn and very committed to the cause in South Vietnam,” he said. While such images fueled the anti-war movement in the U.S., they served to reinforce Luong’s determination to continue his family’s legacy of military service. “That’s the ethos I was raised with — that as ugly as war is, it’s important to sign up to defend your country.”

Luong believes that among Vietnamese who arrived in the U.S. as young adults and those who served in the South Vietnamese army, anger still lingers over what is perceived as a sense of abandonment, even betrayal, by the U.S.

“Resentment persists among the diaspora, especially among South Vietnamese officers and those left behind to suffer communist re-education camps and all the oppression that followed,” Luong said, noting that he personally doesn’t have those feelings, although his father and his father’s comrades certainly did.

“Looking at the last years of that conflict and talking to some of the very few remaining U.S. advisers in Vietnam, we learn that the South Vietnamese fought for the most part heroically. Yet, in movies and the media, they weren’t positively portrayed.” Luong feels the suggestion that somehow they didn’t do their part or were a bunch of cowards who didn’t defend their homeland, is very painful to his father’s generation.

“That hurts even more than the sense of abandonment,” he said.

Ross stresses that the film studios largely remained silent on Vietnam until after the war was over.

“Hollywood is in the money-making business not the consciousness-raising business. It didn’t want to risk being accused of a lack of patriotism, so it avoided putting out films critical of the war until it was over,” Ross said. The Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now — these films changed our post-war view of Vietnam, recasting it as our very own personal horror story.

However, Nguyen warns there’s a real danger in arguing that any kind of atrocity or war is unique, or more horrific, than any other. “What that means is that we’re personally invested in it,” he said. “Our war, our horror, is more unique than other peoples’ and that’s actually not true.”

The deaths of 3 million Vietnamese and 3 million Cambodians and Laotians during and after the Vietnam War represent horror on a grand scale. Yet we must not forget, Nguyen reminds us, that 6 million Jews and 20 million Russians died during World War II, and that 800,000 Rwandans were slaughtered during the Rwandan genocide.

“What is really horrific about the Vietnam War is that it wasn’t unique,” Nguyen said. “The fact that 6 million people died during a war was actually not unique during the 20th century. That is the most horrific thing about it.”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2016-Spring 2017 issue >>