Gray Whale breaching off the coast of Dana Point. Source: Captain Dave’s Dolphin and Whale Watching Safari

8. Behemoths of the Sea: Whales and Ships

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

Twin behemoths ply the seas near us. Both are huge, but only one is visible. The other remains mostly invisible to all but fortunate boaters. One resides under the sea—whales—while the other—ships—can be seen by us all, bringing cargo to our shores. Yet the two share ocean space in Southern California coastal waters, and that can be problematic for both, especially in the Santa Barbara Channel; the area between the mainland and the Channel Islands where a shipping lane is located near a concentration of whales and where there is always a danger of the faster-moving ships striking the slower whales, injuring or killing the large mammals. Technologies to provide real-time monitoring of the presence of whales or provide reliable advice to mariners are being developed, and over the past decade, collaborative action has been taken to discuss the steps needed to reduce ship strikes (the striking of whales).

The Natural Environment

The coastal waters of Southern California support a wide and diverse variety of marine organisms, many of them indigenous, while others are transient. Among those species visiting our waters are large cetaceans (whales), including gray whales, as well as endangered species like blue, humpback, and fin. Gray whales pass through a nearshore corridor in their movement from colder, nutrient-rich northern waters off Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington in the spring and summer to warmer southern waters off Baja California in the fall and winter. Humpbacks and blue whales migrate in the opposite direction, from south to north, and fin whales tend to migrate further offshore. A welcome resting stop along the way for these species are the Channel Islands off the coast of Santa Barbara. Further, this stop is a feeding ground for species like the blue and humpback whales. The five islands, San Miguel, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, Anacapa, and Santa Barbara, that constitute the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (CINMS or “the Sanctuary”), are uninhabited. Their clear, cold waters provide ample opportunities for our biannual marine visitors to pause along their journey, rest, feed, and prepare for the next leg of their trip. The absence of people on the islands provides a safe, calm, and clean environment for these large mammals.

The Problem

The configuration of the four northern member islands is such that none is more than 50 miles offshore, and that between the islands and the mainland is a reach of ocean that is protected from southern storm events. However, whales and other marine animals are not the only users of these waters. For centuries, ships have also used these protected waters as safe harbors in winter storms, and, more recently, as a designated route for vessels moving along the coast. Since 1999, the route has been memorialized on international navigation charts as a “traffic separation scheme (TSS),” which defines both northbound and southbound lanes for ships moving through the sound between the mainland of Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties, and the Channel Islands. This corridor is not a trivial matter: abiding by the TSS reduces uncertainty for mariners about the intention of other vessels in the area, and reduces the likelihood of collisions at sea and subsequent environmental spills. The corridor originally consisted of two lanes, each one nautical mile wide, with a two-mile buffer lane between them. One is for northbound ships, the other for those heading south, and the buffer lane is designed to prevent bow-to-bow encounters between opposing vessels.

Unfortunately, the ocean space south of Santa Barbara County is historically a multiple-use area. Whales and other species have inhabited these waters for millennia, and shipping has been in these waters for hundreds of years. More recently, large swathes of these coastal waters are used as a downrange safety area by the Department of Defense (part of the Point Mugu Sea Range, formerly known as the Pacific Missile Test Range) for missile launches from Vandenberg Air Force Base and US Navy airborne gunnery and missile practice. In addition, the area is fished commercially, and offshore oil rigs dot the waters. Between large container vessels, fishing boats, and the military, it is an understatement to say that whales are not alone in these waters.

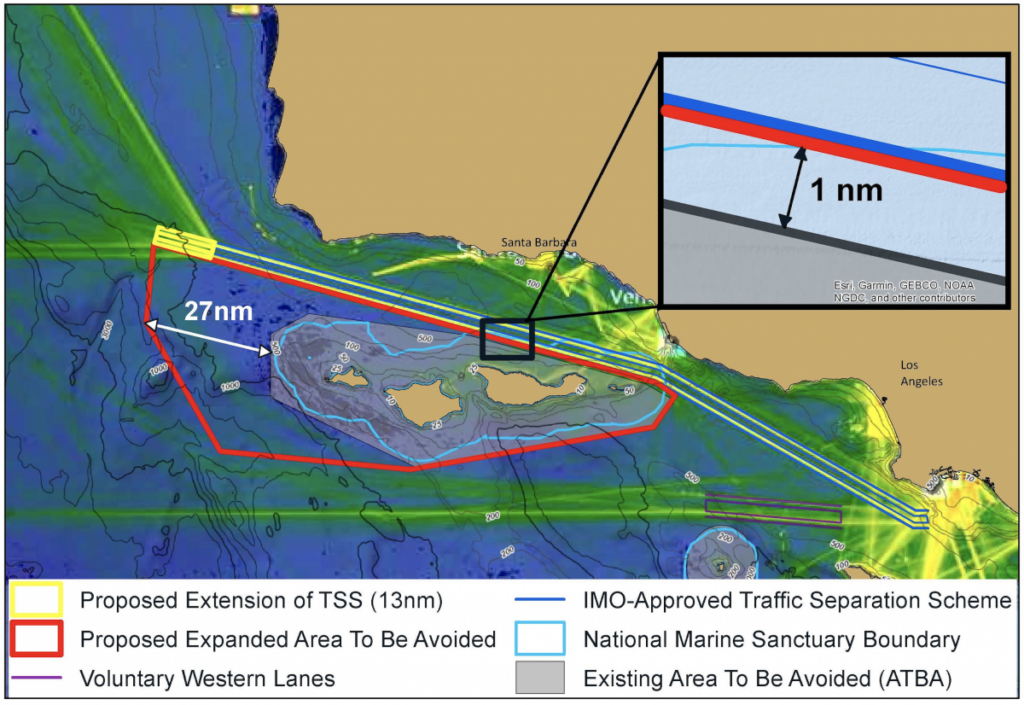

In 2013, a small change was made in the southbound lane of the TSS, moving it one nautical mile to the north (further away from the Channel Islands and thus further from their shallow, nutrient-rich coastline). This change was to shift the ships away from historically important whale feeding habitats. The change did not affect the alignment of the balance of the TSS because the one-mile adjustment of the lane merely took away one mile of the buffer zone between the two lanes. Thanks to current advanced navigation technology[1] not available in 1999, the US Coast Guard and maritime communities agreed that the loss of a part of the buffer zone was tolerable, would not affect the northbound TSS lane, and would not endanger bow-to-bow passage of vessels in the lanes.

The Greatest Challenge: Whale Data

A significant challenge in developing a workable management program was to identify the numbers, concentration, and location of whales in these waters to enable mariners transiting the channel to take evasive action to avoid them. Since 2013, daily ship traffic adjacent to the Channel Islands (both south of the islands and in the Traffic Separation Scheme on the northside) has been very consistent at 7-8 transits per day northbound and similar counts southbound. In a similar situation off the Stellwagen Bank Marine Sanctuary in Massachusetts, humpback whales gather at the location of another shipping track at the entrance to Massachusetts Bay. However, in that case, the concentration of animals is greater in a smaller area and sophisticated monitoring is possible because of that concentration. Approximately 5,000 transits per year are made in Massachusetts and about 5,500 in Southern California. The protected area of the Stellwagen Bank is about 10-12 miles in width at the edge of the bank where whales congregate, while the Santa Barbara Channel is more than 60 miles in length and 10 miles wide on each side of the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary[2]. Thus, in the Santa Barbara Channel, whales are spread over a broader area, much of it 30 or more miles from the mainland, making monitoring a challenge of monumental proportions for biologists.

Further, research is needed to continually update the magnitude of whale populations in the area. By involving the marine science community with the military, shipping industry, and other users of these waters, it was found that additional data and funding for research on topics including the frequency of visits, size and nature of the population, and annual use characteristics of this portion of their habitat, can further enhance the development of policy regarding traffic lanes and protecting whales.

Marine Shipping Working Group

Seeking ways by which whales and humans can share this ocean space, from 2014 to 2016, CINMS sponsored a two-year Marine Shipping Working Group (MSWG) consisting of more than 30 members from the Sanctuary, academia, the shipping industry, the U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Coast Guard, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Santa Barbara County, the National Park Service, environmental groups, marine industry representatives, California agency representatives, and the USC Sea Grant Program. Ambitiously, the group met frequently over the two years and crafted both a thorough analysis and a list of recommendations for protecting the whales and providing guidance to mariners sailing along our coast.

Led by a third-party facilitation team and assisted by SeaSketch, a technical mapping group from the University of California, Santa Barbara, the Working Group spent much of the first year in research to locate information from the parties about the natural history of whales in this area, the marine geography of the area, shipping frequency, the nature of that industry, and the needs of the various ocean space users, including the U.S. Government.

The mapping team urged the parties to suggest alternative routing for vessels using its interactive mapping software as information became available from the experts in the Working Group, and those data were incorporated into various alternative maps. Every participant in the group had a chance to envision what each conceived as a workable alternative to the current traffic patterns. The proposed alternative options are outlined below.

After the parties had a chance to present their views of alternative strategies, the group enlisted the help of experts on the process of charting to comment on various categories of information that can be presented on charts as well as the process for incorporating new information on nautical charts, which are legal documents. Thus, proposed changes must be vetted not only by the U.S. but also by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) because mariners worldwide will rely upon the representations made on these documents. Among the ideas considered by the MSWG included the following: 1) providing additional physical space for these mammals, and 2) modifying the manner in which shipping used its separation lanes.

Evaluation of 2013 TSS Change

The Working Group evaluated the small change made in the southbound lane of the TSS in 2013 and its usefulness in protecting whale populations. In addition to the primary focus of the study, Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties sought to improve air quality and proposed that moving maritime shipping further offshore could assist the counties in that objective, therefore, the Working Group acknowledged these interests in the project.

ATBA Proposal

Charts and ancillary marine safety publications can advise mariners to beware of certain areas of ocean space, one of which is an “area to be avoided” or ATBA[3]. Commonly, an ABTA is declared to avoid environmental damage or a safety zone in proximity to fishing grounds or environmentally sensitive habitat areas. One such ATBA was proposed as a means of protecting the waters to the southwest of San Miguel Island, the westernmost of the Sanctuary, but it did not envision rerouting the TSS.

New TSS Location

Another proposal suggested an additional TSS that would define an approach to/from the twin ports at Los Angeles and Long Beach and would be located in a northwest-southeast orientation south of the Channel Islands. As discussion evolved in the Working Group, it became clear that the alternative proposed would need approval by the U.S. Coast Guard, NOAA, and the U.S. Navy before it could be proposed as a chart amendment to the International Maritime Organization, and each of the federal government entities and maritime communities expressed positions that were inconsistent with one another. This was in part a result of a lack of data as to where the whales were located in these offshore waters.

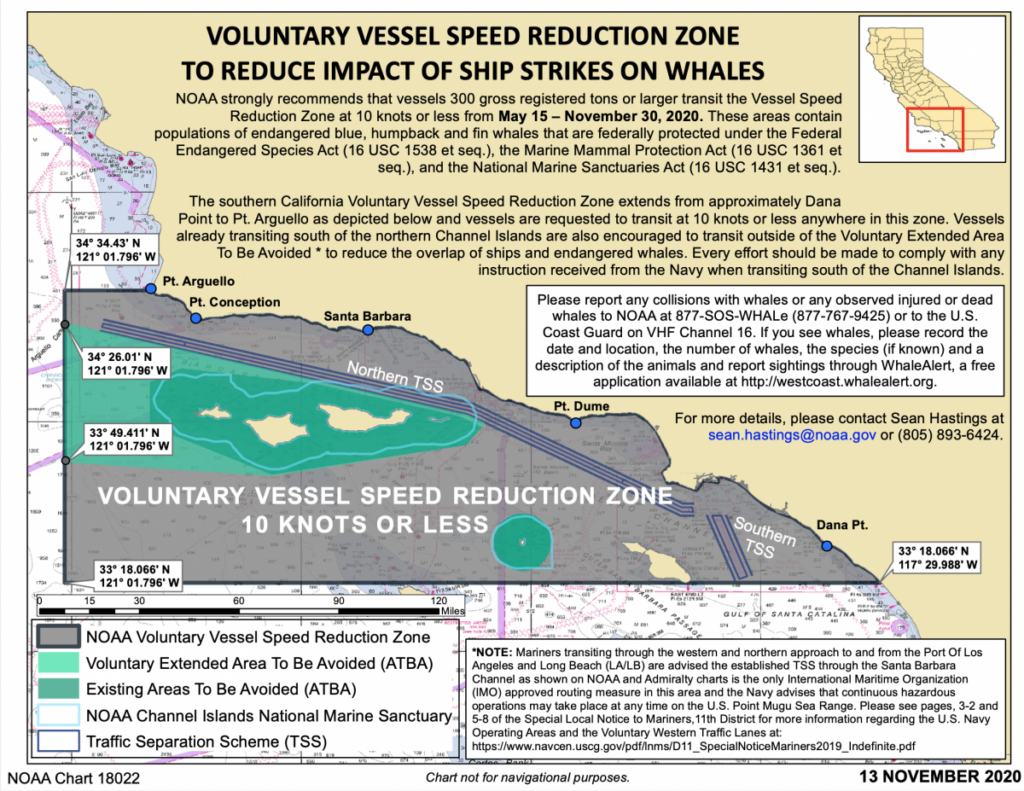

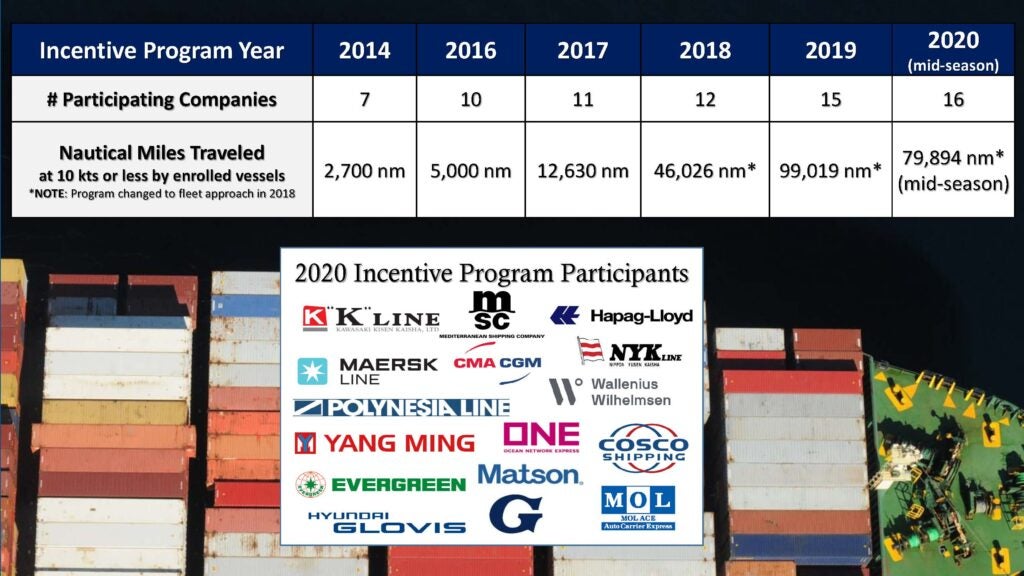

Speed Reductions

Other proposals involved urging mariners in large vessels to slow down when whales are known to be present in the sound and during active feeding seasons from March to November. One voluntary scheme was tried to financially reward vessels that slowed during critical times of the year. However, the major impediment to implementation and verification of success was inconsistent information at that time about the location of whales while vessels are in the nearby waters. Vessel operators expressed the view that they were eager to avoid whales in the area both from an environmental perspective and because mariners have an aversion to striking these large mammals. Moreover, vessel safety is also an issue if vessels were to be constrained to a 10-knot speed limit during feeding seasons, especially in windy or stormy weather. An additional consideration was that if a mandatory speed reduction were implemented, it may have adverse economic consequences for the two seaports in San Pedro Bay, the California economy, and the U.S. economy.

Military Limitations

As noted above, an alternative proposal arose to designate an alternative (and additional) TSS south of the Channel Islands into deeper water. The theory was that by encouraging mariners to use a more southerly track, they would avoid a large number of the mammals, and the TSS would, itself, provide mariners the safety needed outside of the channel. The mariners were amenable to this alternative track even though it would take many months to seek approval by the U.S. Government and then by the International Maritime Organization in London. While they were joined in this position by the biologists, ultimately the decision was opposed by the military because a proposed southern TSS would be within the waters of the Point Mugu Sea Range. Designation of a TSS in this area would de facto indicate that transits were safe when, as the representative of the U.S. Navy explained, the designation would interfere with an established test missile range. Current practice is to warn mariners in advance of firing exercises on the range via Notice to Mariners and radio warnings for vessels to stand clear. Experience has demonstrated that the current system works effectively when the range is used, and, at other times, vessels are free to sail within it.

Working Group Findings

After two years, the Working Group completed its work and highlighted the outcomes of its work in a report. Ultimately, it recommended that the 2013 change in orientation of the southbound lane, moving it one mile north, away from the Channel Islands, and thus narrowing one mile of the buffer zone between the northbound and southbound lanes of the TSS, offers some relief to the whale population. This is also true for voluntary speed reduction schemes that encourage mariners to slow down to 10 knots during the months of the most populous whale congregations. However, more discussion is needed as biologists would prefer a clearer separation between the animals and ships. As a result of the work of the MSWG, however, a proposal extending the channel TSS to the west near Point Conception is now being considered by NOAA and the U.S. Coast Guard.

The research and outreach efforts resulted in a major exchange of ideas and information between the various parties within the Working Group and made strides to open lines of communication between them, enhancing opportunities for further collaboration to devise protection schemes for these large cetaceans. Nevertheless, impediments arose to creating an entirely new scheme to either revise the traffic separation scheme or introduce an alternative TSS outside of the Santa Barbara Channel.

What Will Happen Next?

On March 16, 2019, the Working Group submitted its report[4] to the CINMS Advisory Council for its ratification and recommendations to the Superintendent of the Channel Islands Marine Sanctuary. The report detailed 14 topics that were explored, resulting in Technology-Based Approaches and Spatial Approaches for further study and evaluation. The Superintendent then forwarded the report to the Secretary of Commerce for further action. The Department of Commerce, through NOAA, now has the responsibility for exploring and negotiating with all relevant parties over the advisability of implementing any of the approaches as a means of protecting whale species in and around the Channel Islands. The Working Group’s effort to explore how whales and humans can successfully share this ocean space made headway in showing how common ideas across partners can lead to collaboration, discussion, and actionable ideas. However, although there was much progress by the Working Group to reduce ship strikes over the last decade, there remains more room for improvement and implementing actions moving forward.

Note: My thanks to CAPT J. Kipling Louttit (USCG, Ret.), Executive Director of the Marine Exchange of Southern California, for his advice and assistance on this complex topic.

References

[1] The systems are known as Electronic Charting and Data Information Systems (ECDIS) and are aboard all documented vessels.

[2] The Stellwagen Bank Marine Sanctuary is 638 nautical square miles in area, while the Channel Islands Marine Sanctuary is 1,110 nautical square miles in sea area but extends only 6 nautical miles beyond the coast of each of the five islands. Whale habitat extends beyond sanctuary waters, farther into the nearby waters.

[3] The definition may be found at 33 C.F.R. § 150.915.

[4] The report can be found at https://channelislands.noaa.gov/sac/group_meetings_archives.html