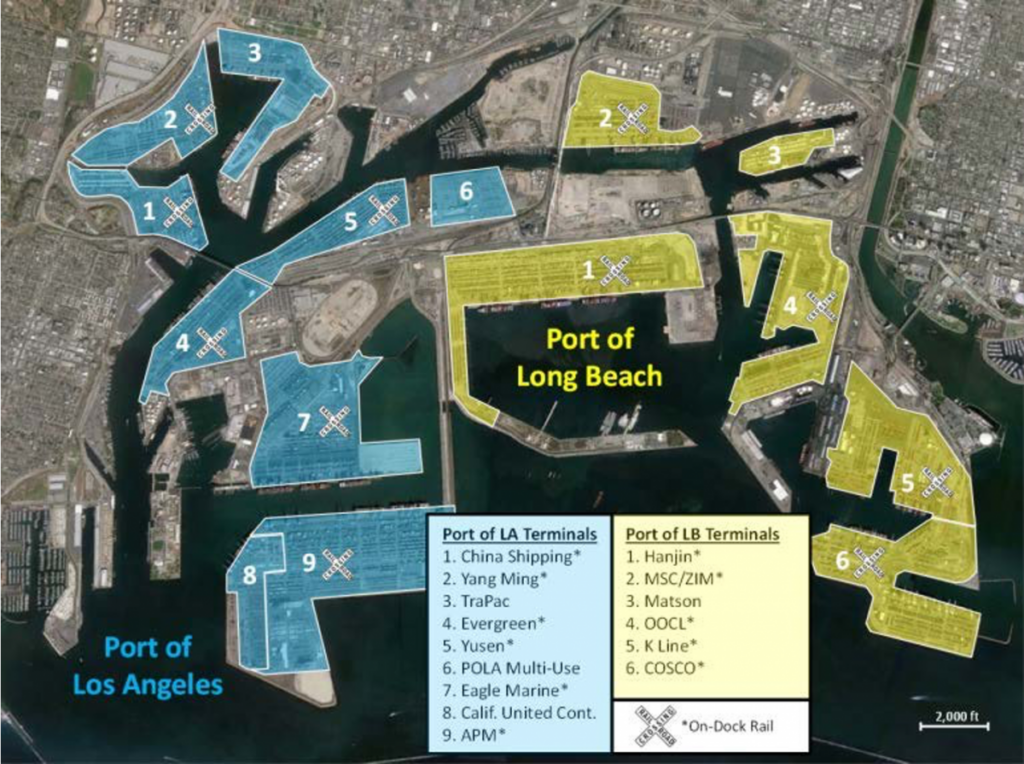

The two ports of Los Angeles County sit side-by-side in San Pedro Bay. Photo: Google Earth

5. Why We Have Two Major Seaports in San Pedro Bay

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

Together the Port of Long Beach (POLB) and the Port of Los Angeles (POLA), the two cheek by jowl mega ports in San Pedro Bay, are the busiest container ports not only in the U.S. but also in North America. Handling almost 17 million twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) containers each year, they dwarf the volume of most other container ports on either coast. How did this happen historically? What is it about these ports that continue their success? The answers lie in geography, railroads, civic pride, economics, and climate.

Geography: Rivers to the Sea

The Los Angeles Basin, surrounded by mountains, is a flat, alluvial plain draining into twin river systems: the Los Angeles River which empties into San Pedro Bay at Long Beach and a smaller river system known as Ballona Creek that discharges into Santa Monica Bay. With the Palos Verdes Peninsula as a fulcrum, the two embayments face the south and the west, respectively at a 90-degree angle. Undeveloped, either would make a viable location for a seaport and, in fact, Collis P. Huntington, owner of the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP), sought to make just such a facility in Santa Monica until his plan was defeated by the City of Los Angeles through the efforts of the owner of the Los Angeles Times, Harrison Gray Otis.

Railroads: The Octopus of Economic Development

Steve Erie[1], Professor of Political Science at UC San Diego describes the Southern Pacific Railroad under Huntington as “the Octopus,” a company that controlled more than 85 percent of the state’s railroad lines. “Its economic stranglehold over Los Angeles was even greater. Representing the interests of San Francisco and eastern capital, the SP treated Southern California as a colony…[i]ts major concerns were its massive federal debt load…and its substantial waterfront, terminal and land investments in the Bay Area.” But, after a bitter fight with the City of Los Angeles, the “Great Free-Harbor Fight” in the 1890s, the City of Los Angeles secured funding for dredging a public port and a long breakwater, winning the fight with Huntington over his proposed, private port at Santa Monica.

Yet, a building boom in the 1880s and 1890s created enough demand that his SP rail route to the east through Yuma, Arizona was joined by the Santa Fe Railroad with a route to Chicago and a third railroad, now the Union Pacific, that would bring coal from Salt Lake City to the growing metropolis. Now with three rail connections to the central and eastern regions, a seaport at Los Angeles was an essential element in the economic development of the region, and a municipally-owned seaport critical to separating itself from dependency on northern California economic interests.

Civic Pride: The Rise of Long Beach

The building boom in southern California in the late 19th Century created a need for lumber, and without forest resources nearby, wood needed to be imported, much of it brought by ship and barge from northern California. As Erie recounts, in 1887, the Long Beach Development Company purchased 802 acres of marshland to begin developing a dock for the city. By 1902, it created the Los Angeles (LA) Dock and Terminal Company and began raising funds to dredge the marsh in order to build its dock. For the next two decades, the private company worked with the City of Long Beach to create facilities for ships facilitated by Charles Windham who served both as a director of the company as well as the mayor of the city. Through his efforts, Craig Shipbuilding was encouraged to become the city’s first port tenant and an early builder of ships for the U.S. Navy, a fact that would later have a significant influence on the harbor.

Craig dredged the harbor and began an industrial base for the city in its new harbor. Still in private hands, nevertheless, in 1922 the City of Long Beach had a new city charter, and, by virtue of its new powers, it created a harbor commission to supervise the development of the port. With new authority embodied in the charter, it also sought to acquire the privately held harbor. Seeking relief from the costs of managing the waterfront and with the support of the public, a harbor bond issued in 1928 gave the city the ability to acquire the rights of the LA Dock and Terminal Company, creating a municipally-owned port, the second in San Pedro Bay.

Terminal Island: Settling Geographic Struggles

Geography and turf struggles between the POLA and POLB were finally settled in 1909 with the division of Terminal Island between the two municipalities and their harbor interests. With the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, both ports now had a unique opportunity to capitalize on their strategic location.[2]

Although the Los Angeles River discharges into the east side of the Port of Long Beach, since the 1930s when the river was channelized in concrete, siltation has been greatly reduced further limiting the amount of maintenance dredging necessary to maintain sufficient water depth in channels and alongside wharves and docks. No comparable watercourses discharge into the Port of Los Angeles, greatly limiting the need for maintenance dredging, a rare advantage—both economic and physical—compared with ports around the world located along rivers or at the terminus of rivers.

Terminal Island, now so important to the operations of both seaports, evolved out of a spit of land originally known as Rattlesnake Island. It was essentially useless for ship traffic as water depths were insufficient and it was an island without the current major bridges to Long Beach, Wilmington, and San Pedro. However, this “little island that could” evolved as shipping channels were dug and the island expanded when dredge material was placed in the nearest and most convenient location, on Rattlesnake Island, renamed Terminal Island in the 1890s.

For decades, the island was a fishing port occupied by a Japanese American community of fishers who were rapidly incarcerated with the start of WWII, never to return to the island. (There is now a memorial to the community next to the LA Fire Department’s station on Terminal Island). During the ensuing war, however, the island became a beehive of shipbuilding and war-related activity with both a major naval base and a naval shipyard. Post-war commercial fishing returned in a big way, notably with the growth of Pan Pacific Fisheries and Star-Kist Co. By 1953, Star-Kist was reputed to be the largest tuna cannery in the world, with large tuna super-seiners fishing worldwide calling Terminal Island their home port.

Economic Advantages

The shift of marine freight to containers in the 1960s and 70s created a demand for hundreds of acres of landside space alongside wharves, not only in these two ports but worldwide. Terminal Island, unlike many other seaports, had a big advantage: it could be widened further by depositing dredge material forming new land for container terminals. The deeper draft ships of the container fleet needed deeper channels, and as channels were dug, again, the dredge material was used to create new land on which container terminals have been built. As a result, over the past 30 years, over 775 acres (315 hectares) of new land has been added to the island on the POLA side. Moreover, the former U.S. Naval Shipyard was converted into a large, 385 acres (156 hectares) container terminal on the POLB side. Recently, the new Long Beach Container Terminal of 170 acres (69 hectares) was constructed by filling slips not in optimum use to create a larger, more efficient, automated container terminal.

World War II was also a major impetus for growth, not only in the ports but also in the southern California economy. The war led to robust aviation industry in the area, which spread throughout Los Angeles and Long Beach and down to San Diego.

A Robust Connection: Driven by a Mild Climate

The creation of two, large ports, side-by-side, would not have been successful had the rail connections to other parts of the nation not been robust. The Southern Pacific Railroad may have been an “octopus,” but it helped spur regional development and inspired other railroads to provide linkages from the region. The rail routes had the advantage of uniformly good weather in southern California, unlike other regions where winter weather impedes rail routes into and out of the West.

Two Ports: Then and Now

Although it may appear strange to the casual observer that two major seaports adjacent to one another are not unified into a single entity, their history cautions otherwise. These two economically sustained ports, enabled by booming industry and transportation by rails, continued to grow and compete to be the largest port complex in North America. As trade expanded between the U.S. and Asia, the ports have been well suited to provide trade links for the rest of the continent. The pace of these two mega ports has not slowed, and their ideal geography, mild weather, rail-linkages, gateway to Asia, and independent civic pride keeps them in competition, as together, they dominate a continent.

References

[1] Erie, S.P. (2004). Globalizing L.A.: Trade, Infrastructure and Regional Development. Stanford University Press.

[2] Erie, S.P., op. cit