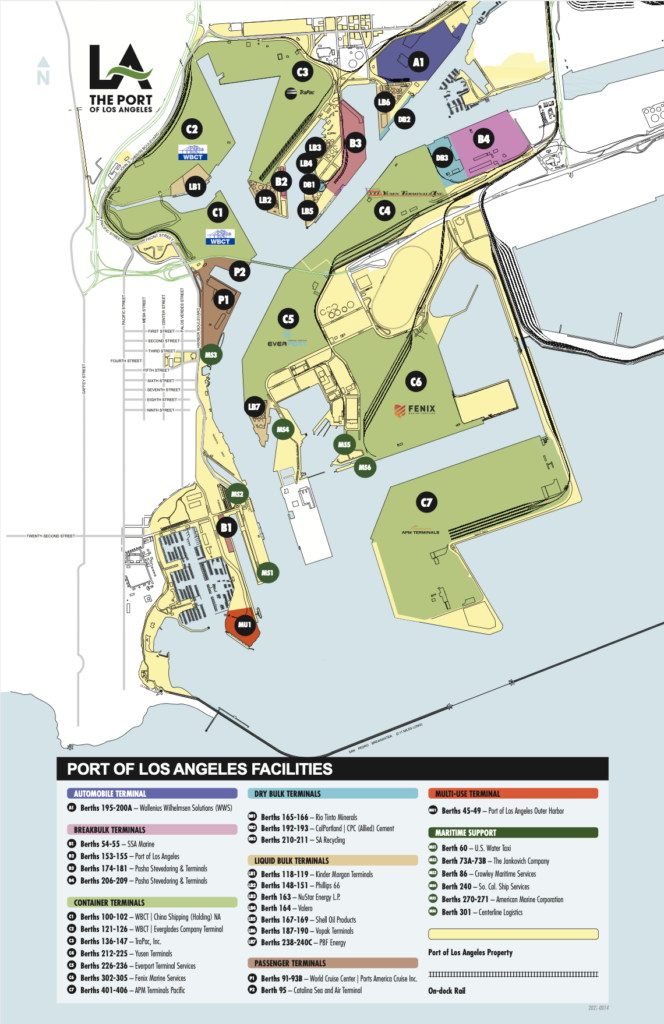

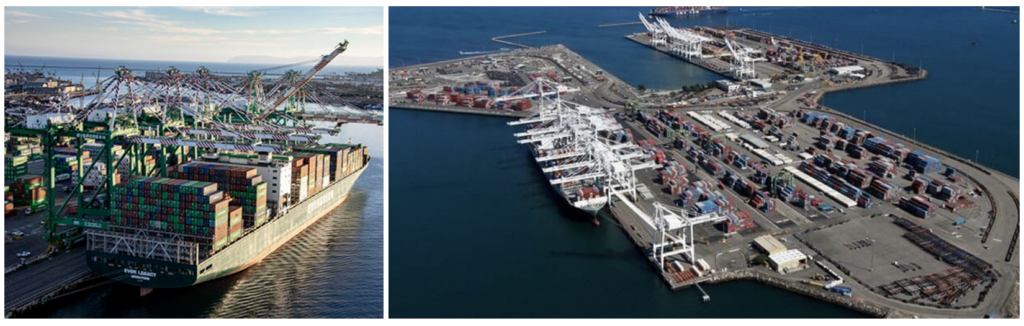

APM Terminals at the Port of Los Angeles is the largest container port terminal in the Western Hemisphere (Source: APM Terminals)

17. Sea Port Terminals: What Are They and Whom Do They Serve?

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

In this Ship’s Log series of articles on seaports and shipping, we have discussed ships and cargo, air quality, port pilots, types of ships, port congestion, and other aspects of the supply chain and seaports. One item, however, that has thus far escaped our attention, is the land that seaports control. Read below to learn about seaport terminals and the important role they play in managing the movement of goods.

What is a Terminal?

At each end of a voyage, on departure and arrival, vessels must moor to a landside wharf or dock to load and unload their cargo. Behind the wharf is dry land where cargo is stored, sorted, as well as loaded and unloaded from other modes of transportation such as truck, rail, or air. This land behind the wharf—the terminal—is a necessary element in the movement of goods. Terminals can range in size from very small to hundreds of acres, all depending upon the type of cargo that is handled. Moreover, the land itself, especially in the U.S. and other Western countries, is rarely privately owned, but instead either managed by the port or leased to the terminal operator.

Land Ownership and Management

Consequently, land in our seaports is commonly state property under a legal principle known as the “public trust doctrine.” And, in California under a 1941 Act of the legislature known as the California Tidelands Trust,[1] the ports manage tidelands, submerged lands, and navigable waters on behalf of the state and for statewide public purposes. Generally, those purposes are defined as commerce, fisheries, navigation, ecological preservation, and recreation. The ports are permitted to operate these lands and derive revenue from those operations if the revenue promotes the five categories noted. Thus, land in the ports post-1941 cannot be privately owned, only leased.

There are generally two types of seaports: 1) “operating” seaports that manage all the land in the port and hire all the dockworkers who work there, and 2) “landlord” seaports where the port provides basic services but the terminals are managed by a company that leases and operates the terminal; the operator subsequently negotiates labor agreements independent of the port. In both cases, “basic services” include maintaining channel depth, wharf viability, utilities, infrastructure, fire protection, and overall port security.

Differences in Terminals

Not all terminals are alike. The Ports of Los Angeles (POLA) and Long Beach (POLB) have approximately 35 terminals each, but they are not of one size or function. Some accommodate roll-on/roll-off (RoRo) vessels that bring imported or domestic vehicles for export including trucks, cars, and other wheeled vehicles. Other terminals handle bulk goods (grain, minerals, scrap metal, liquid bulk such as chemicals or oil, or other commodities that are not carried in containers) or breakbulk cargo (the predecessor method of handling crated or palletized freight prior to the development of containers). Yet others are designed to support the containerized cargo.

Each type of terminal is equipped with dedicated machinery designed to support the specific type of cargo handled there, thus each type of cargo needs its own specific type of terminal. The sizes of terminals also vary depending upon the type of cargo. At some terminals, such as those handling liquid bulk, the terminal consists mainly of connections to a pipeline that moves the liquid out of the port to an offsite storage area; the actual terminal may have little more than a berth large enough to accommodate a tank ship, a pipeline connection, and a surge tank. At the other end of the spectrum are capacious container terminals of 100 acres or more, space that is needed for storage of thousands of incoming and outgoing containers. These are the biggest terminals in any port; POLA hosts seven container terminals and the POLB hosts six.

There are considerable variations in sizes and infrastructure at the various terminals depending upon the type of freight. For example, both ports at one time had bulk terminals for exporting petroleum coke (pet coke), a residual product from the oil refining process that is high in carbon content and can be used either as a fuel or as carbon in other industrial processes. From our local refineries, pet coke was delivered to the ports in bulk, stored in sheds, and bulk loaded into carriers for export. The process involved space for storing the bulk product, a loading system to deliver the product to the ship, and a berth, all of which required substantial dockside space. An even more expansive use of port land is RoRo terminals that are essentially huge, surface parking lots onto which imported vehicles are discharged and stored until they are transported by train or auto carrier to their ultimate destination. These terminals have little in situ infrastructure but may be sizeable, with space for large numbers of vehicles; a single ro-ro vessel can transport as many as 5,000 cars.

One of the oldest terminals in the POLA has been in operation since 1923, has a capacity of one berth on 7 acres, and is owned (its ownership preceded the 1941 California Tidelands Act) by Rio Tinto Minerals; it is known as the 20 Mule Team Borax terminal at berths 165-166. Its facilities include silos for the storage of export borate products.[2] Another small terminal in the POLA is CalPortland | CPC (Allied) Cement at berths 192-193, which has silos for the storage of cement. In the POLB, Morton Salt at Pier F handles bulk salt in a terminal of just five acres with only 2.7 acres of open area for storage. It contains a movable incline elevated electric belt conveyor system from the wharf to the stockpile area, and contains an adjacent packaging plant.[3]

The Uniqueness of Container Terminals

Container terminals are very different, not only in scope but also in facilities. Like ro-ro terminals, they are large parking lots for intermodal containers, but unlike automobiles, the containers are made to be stacked and organized to conserve space. Sitting on the terminals are export containers waiting to be loaded aboard a departing ship; import containers waiting for customs clearance; import containers waiting to be delivered and empty containers waiting to be redeployed or waiting to be returned overseas. For the “empties,” recent emphasis has been on moving them off the terminals to storage yards where they can be landed (stored on the ground) to wait without congesting terminal operations.

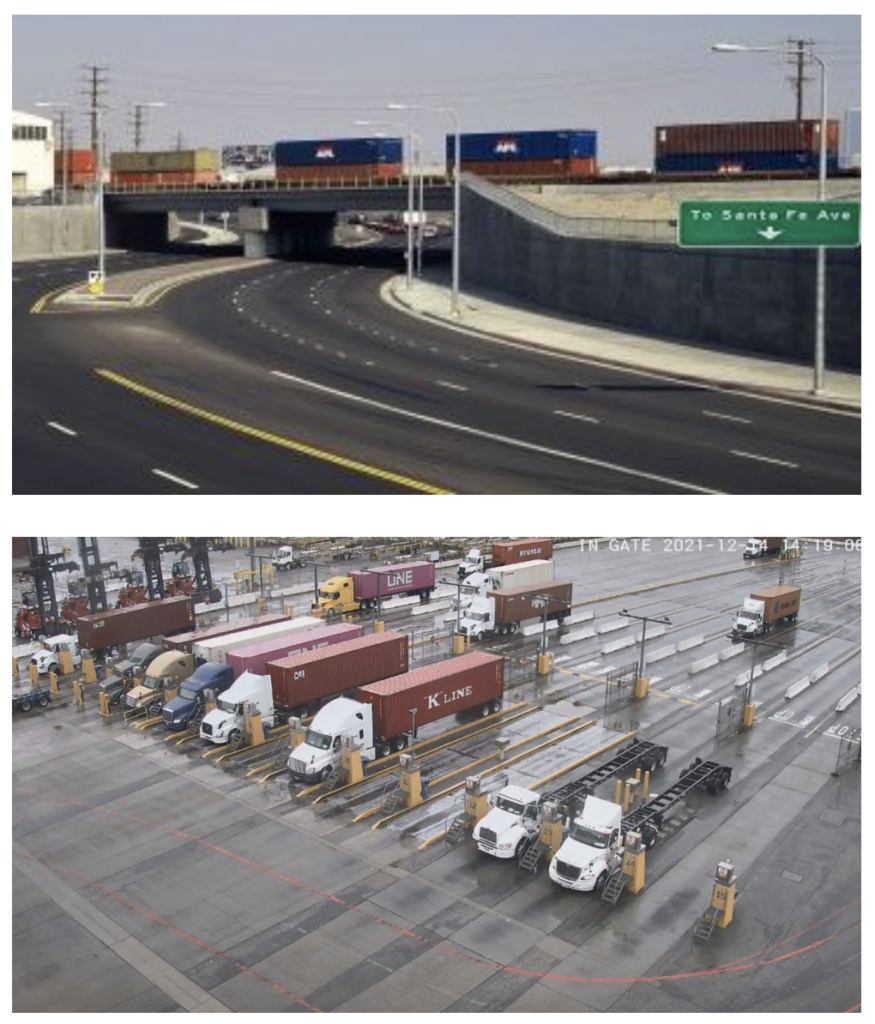

On the operational terminals are maintenance facilities for equipment needed to move containers on the yard (often a customs office), offices for the terminal management, and gates through which truckers bring either export containers or empties back to the yard. Perhaps most obvious at the operational terminals are the huge container cranes that load and unload ships. Many of these terminals are leased either by the same company that owns the ships or by a U.S. subsidiary of those companies. For example, in the POLA the terminal serving Evergreen Lines (a Taiwanese company) is leased by EverPort Terminal Services with home offices in Los Angeles. Situated on 205 acres, the terminal hosts three berths on 5,800 feet of waterfront, with six post-Panamax cranes.

Similarly, in the POLB at Pier J, SSA Marine (Stevedoring Services of America, a U.S. company based in Seattle since 1949) leases an area of 256 acres with 5,900 linear feet of wharf with on-dock rail with a capacity of 83 railcars and with 17 gantry cranes.[4] These long wharves are necessary because some of the newer container vessels are now more than one thousand feet long, and it is often necessary to berth more than a single vessel simultaneously. In addition, the landside of the terminal must concurrently be able to accept the large number of containers discharged from one or more of these massive container ships.

Terminal Infrastructure

Terminals by themselves are dependent upon civic infrastructure for their success. Whether an operating or landlord seaport, utilities must be sufficient to support port operation. With the introduction of the Clean Air Action Plan in 2006 both ports agreed to make adequate electrical connections allowing all vessels, especially container vessels, to connect to shore power when in port, thus shutting down their onboard diesel auxiliary power units. That has largely been completed by both the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power in the POLA and Southern California Edison in the POLB. On-dock rail spurs (rail links directly to docks where containers are unloaded from vessels) and the multi-billion dollar Alameda Corridor rail link to Vernon near downtown Los Angeles have now been installed in both ports, making transfers of containers to long-haul destinations more feasible than ever. Prior to these direct rail connections, containers had to be transferred from ship to truck, driven across Los Angeles to the rail station where the containers were then backloaded onto rail cars. For local delivery (500 miles or less) containers are carried by truck. The new replacement bridge for the Gerald Desmond Bridge allowing trucks to easily access Interstate 710 from Terminal Island has also facilitated cargo movement, all of which assists the industry to move cargo more rapidly from the two ports to the region and the nation.

Future Considerations

However, as container ships become ever larger, bringing larger volumes of freight to our ports, they also will do so by bypassing ports that do not have sufficient channel or wharf side water depths. POLA and POLB will be the beneficiaries on the West Coast in terms of cargo volume, but that may be a two-edged sword. There is likely a point of diminishing returns where the time necessary to unload and process ever-larger volumes of freight in short pulses creates delays in the goods movement system that overwhelm the cost savings of moving huge volumes of cargo on one single vessel. It may also overwhelm the container terminals that were state of the art when they were constructed mere years ago. As the current congestion at our ports abates and we return to equilibrium, only then will we be able to assess how well our current infrastructure, both civic and maritime, is built for the near future.

References

[1] Illinois Central Railroad v. Illinois, 146 U.S. 387 (1892); also California Tidelands: Lands Held in the Public Trust, Understanding the Public Trust Doctrine, https://pantheonstorage.blob.core.windows.net/administration/California-Tidelands-Land-Held-in-Public-Trust.pdf.

[2] Port of Los Angeles. Port and Terminal Map. https://www.portoflosangeles.org/business/terminals/dry-bulk/rio-tinto-minerals.

[3] Port of Long Beach. Online port map. Pier F. Morton Salt Terminal. https://polb.com/port-info/map.

[4] Port of Long Beach. Online port map. Pier J, Pacific Container Terminal. https://polb.com/port-info/map.