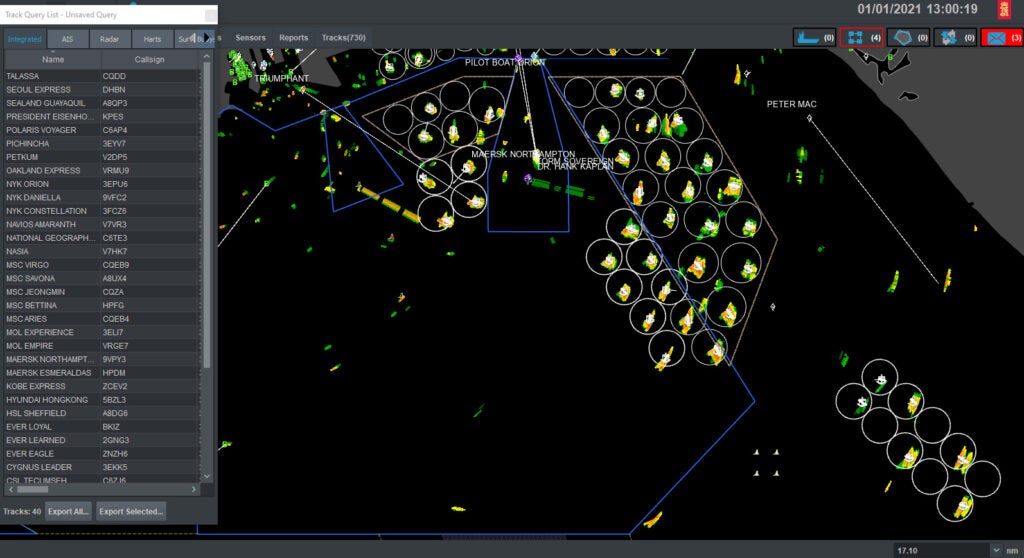

A snapshot on January 21, 2021, showing the abundance of ships anchored. Source: Captain Patrick Baranic, MX General Manager

11. Port Congestion and the Supply Chain: When Did All Those Ships Arrive?

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

Some of us may have observed a strange phenomenon in our twin seaports at Long Beach and Los Angeles over the past three months. Our ports have been host to a much larger array of vessels than normal, and there is a major increase in ships at anchor waiting for space at our docks. In this article, we will explore why that is, to what extent COVID is a cause, and what we can expect in the near future.

In one sense, what we are watching is akin to the classic scene of Lucille Ball (as “Lucy”) working as a line employee packaging chocolates. The chocolate maker continued to make candy at a rate that exceeded Lucy’s ability to package them, so she began eating them to absorb the excess. With no one to “eat” the excess of ships, they sit idle at our offshore anchorages waiting for the chance to unload.

The Supply Chain as a System

Last year began with the hint that there was a hazard from some kind of new virus, and by March 2020, it became clear that we needed to mask, social distance, and avoid crowds as much as possible to stay safe. It affected us all, and while some could hunker down at home, many of us were in industries in which working from home was not an option. The goods movement industry consists of many of those occupations, and it is important to remember that the supply chain is a system; problems with one part of the system have the ability to affect the entire system.

Ultimately, manufacturing and transporting the finished product relies upon talented people, from those who make it, to the folks who move it to the ships that take it across oceans, to those who deliver it to the store or your door. Practically, this includes ship’s crews that transport the cargo, and dockworkers that load and unload the ships, as well as move the cargo—much of it in containers—on the nation’s docks. It also includes the customs agents that clear the cargo, truckers that move it, railroad workers that haul it over long distances, distribution warehouse workers, and, ultimately, the sales teams who facilitate our purchases. Every one of those positions is an integral part of the supply chain, and, like any chain, a broken link will endanger the integrity of the entire chain. Therefore, when we think of the impact of COVID, it can and has affected the entire process of moving goods from one place to another. Even just the act of social distancing can slow the chain.

Tracking Increased Ocean Trade

The Marine Exchange of Southern California and its associated Vessel Traffic Service tracks all vessels entering or leaving the twin Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, as it has done for almost a century. CAPT J. Kipling Louttit (USCG, Ret.), its executive director, notes[1] that, starting in September 2020, the combined volume of vessels either in port or at anchor averaged in the mid-60s on a daily basis. Often, tankers would be at anchor waiting for an opportunity to offload petroleum destined for nearby refineries in Long Beach, San Pedro, and Carson, CA. There would also be a few ships stopping in Southern California to purchase fuel at economical prices, whose visits did not involve loading or unloading cargo. Occasionally, there also would be a vessel waiting for repairs or some other emergency.

In general, however, container vessels would rarely be at anchor. Instead, they would be at berths loading or unloading to maintain their liner[2] schedules, and when loading was complete, they would be on their way to their next port. The extent of facilities in both ports, while ample, were designed to accommodate the needs of customers not only in the Southwest but across the nation as this is a major “load center” for the entire U.S.

Why have the two ports become so unusually busy over the past few months? It has risen to a level of congestion that is exceptionally unusual, even for the busiest cargo seaport in the nation. CAPT Louttit notes that for the past few months, the ports have been hosts to over 100 vessels, sometimes occupying all of the offshore available anchorages that extend south of the Los Angeles-Long Beach breakwater as far as Huntington Beach, and leaving others in temporary “drift box” overload anchorages.

For container vessels, being stalled in an offshore anchorage is a disaster because vessels are on a scheduled route; a delay in the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach means that the balance of their voyage will also be delayed, and cargo will be delayed in its route to the final customer. The global supply chain is just that—a chain—consisting of links that connect a shipment of cargo through the hands of many people, organizations, agencies, modes of transportation, and customers. The burgeoning ship traffic last fall was not simply the result of more ships calling on our two ports. Rather, it was a symptom of a slowing of the entire chain both because of missing personnel as well as increased demand for goods for those of us stranded at home. Most recently, we all saw the slowing (and halting) of the global supply chain when the Ever Given container ship was stuck in the Suez Canal for almost a week.[3]

Delays Due to Illness Absenteeism

Vessel congestion is exacerbated too by illness absenteeism on the U.S. side of the Pacific. Public officials representing the ports and their home cities have spoken as a group about the loss of time and lives from the impact of the pandemic to members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) that represents dock workers, especially in Southern California.

As we continue to weather the current COVID-19 surge, especially in Southern California, port workers contracting COVID-19 could have disastrous consequences for the movement of goods, food, and medical supplies that Californians are depending upon in this time of crisis. This includes especially critical pandemic response goods such as personal protective equipment (PPE), sanitizer, medical equipment, and more. Moreover, emergency regulations recently promulgated by California’s Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board could further exacerbate constraints on critical supply chains if workers fall ill by requiring continuous testing of all employees and taking exposed individuals out of the workforce.[4]

Similar impacts have been felt in the trucking and railroad portions of the supply chain, the consequence of which has slowed the delivery of goods throughout the region and, as Murphy notes, the entire West Coast.

The Increased Demand of Goods in the U.S.

COVID has both direct and indirect effects on the supply chain. Certainly, delays in our economic activity throughout the world are attributable in some respects to illness and absenteeism of workers along the chain. But there is another effect as well: increased purchases of imported goods attributable to unique needs of a population that is sequestered at home. In addition, many Americans have chosen to order goods online which in non-Covid times they might have chosen to purchase in person at local stores. The increase of imported goods include furniture (desks, office chairs, file cabinets, lighting, partitions, etc.), electronic office equipment (computers, screens, etc.) and home entertainment equipment such as televisions and gaming supplies. Many of these goods are made in Asia, and increased demand in the U.S. has taxed the marine supply chain to deliver. Let’s take a look at the demand, and specifically U.S. demand, for goods that are not made domestically; today, that can be almost anything.

Writing in Deloitte Insights[5] Daniel Bachman believes that real imports of goods and services for 2020 will show a 10.9% decline over 2019 and that it will then expand over that amount by 4.8% in 2021. The shock of COVID resulted in reduced economic activity until we learned to adapt to our new circumstances but having learned to adapt, economic activity is now returning and resulting in changes in the goods demanded. In the fourth quarter of 2020, six to nine months into the pandemic, the predominant categories of cargoes shipped from Asia to the U.S. West Coast were furniture, electronics, appliances and plastic goods.[6]

Alan Murphy of Sea-Intelligence Maritime Analysis and Consulting, a container analytics firm based in Copenhagen, anticipates that the current glut of container ship deliveries will likely continue to the Canadian and U.S. West Coast until at least June 2021. Taken from the PIERS (the import/export reporting service), International Journal of Commerce reporter, Bill Mongelluzzo cites figures that show monthly container increases of 10% each month since July 2020 as compared to the same months in 2019.[7] Moreover, the usual two-week hiatus in deliveries as Asia celebrates the lunar new year did not take place this year, as Asia has maintained its manufacturing capability through the annual holiday period in response to earlier slowed production due to the COVID pandemic. Asian producers are now increasing production, responding to domestic U.S. demand, and ships are arriving loaded at Southern California ports.

Additional Demands Due to Vessel Size Increases

In this mix of causation, one other factor should be acknowledged: the vessels that constitute our container ship fleet have become larger. As I’ve noted in earlier issues of this series, as recently as ten years ago, the usual size of a container vessel accommodated between 7-10,000 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units). However, the efficiencies of large container vessels have become evident to the industry and now both ports host ships that carry 14-18,000 TEUs, each one of which requires additional longshore crew for loading and unloading, additional time at the berth, and an additional burden on the rail and road system upon arrival. The ports can handle these megaships, but when multiples of these large vessels arrive, they tax the logistics system because each is equivalent to as much as two vessels of an earlier era. The rapid pulse of increased goods adds pressure on a logistics chain already burdened by diminished personnel due to the pandemic.

Port Congestion Forecast for 2021

Considering the impact in March 2021 and based on the observations of seasoned experts in the industry such as Bill Mongelluzzo, Alan Murphy, and CAPT Louttit, we likely can expect congestion to continue until summer. A trip to San Pedro or Long Beach will quickly confirm their assertions; every container terminal is occupied with ships heavily loaded and vast stacks of empty containers waiting to be returned to Asia. A further simultaneous upside and downside is that both President Biden and Senator McConnell have anticipated that the economy will see a robust recovery in the second half of 2021. If true, that will coincide with the busiest season for our two ports as imports for the late fall holiday season begin arriving from abroad. Truly, this is likely to be a year to remember at our busy seaports.

References

[1] Louttit, J.K. 29 Jan 2021. Personal communication.

[2] Vessels in liner service make port calls on a regular route and schedule much like airlines, generally charactering the operations of container ship fleets. In contrast, bulk cargos are often transported based on an as-needed basis, referred to as “tramp” service.

[3] New York Times. (29 March 2021.) With the Suez Canal Unblocked, the World’s Commerce Resumes Its Course. https://www.nytimes.com/live/2021/03/29/world/suez-canal-stuck-ship

[4] State Senator Lena Gonzalez, State Assembly member Patrick O’Donnell, Congressman Alan Lowenthal, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia, Los Angeles Councilmember Joe Buscaino, and Long Beach Councilmember Cindy Allen wrote to state officials on Jan. 12. https://www.ilwu.org/covid-19-pandemic-a-year-of-record-highs-and-devastating-lows/.

[5] Bachman, D. (16 Dec 2020). United States Economic Forecast, Fourth Quarter 2020. Deloitte Insights Online. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/us-economic-forecast/united-states-outlook-analysis.html.

[6] Murphy, A. (04 Feb 2021). Container Shipping Outlook: Analyzing the Trans-Pacific (webcast sponsored by the Journal of Commerce).

[7] Mongelluzzo, B. (19 March 2021). Waiting for summer. International Journal of Commerce, 22(7), 18-19.