On Writing and Redemption

Mark Richard didn’t intend to write his latest book.

He had originally set out to explore the death of Nat Turner, an early 19th-century slave insurrectionist in Southampton County, Va., where Richard lived as a boy. But Richard’s editor and publisher Nan Talese suggested that the real story was how he grew up and evolved into a writer from this area, a place where a fellow student brought a grotesque heirloom of Turner’s execution to Richard’s 5th grade show-and-tell.

“I didn’t think there was anything unusual about my life. I didn’t think it was worth examination,” said Richard, a lecturer in USC Dornsife’s Master of Professional Writing (MPW) Program. “Then I started writing, and it came to this place, House of Prayer No. 2.”

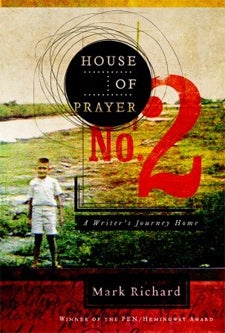

Published in February, Richard’s memoir has won a 2012 Pushcart Prize for nonfiction, awarded annually to the best work published by small presses. An excerpt from his book appeared in The Southern Review and was nominated for the prize by the literary magazine’s late editor Jeanne Leiby.

House of Prayer No. 2 is the story of how Richard grew from a “special child” in the South to a writer in Los Angeles. It’s also an account of the ebb and flow of seeking and resisting faith that he experienced throughout his life.

House of Prayer No. 2 was published in February by Nan A. Talese.

Born with deformed hips, Richard was told that he would be relegated to a wheelchair by age 30. He spent years at a charity hospital in a ward with children suffering from cancer, deformities, debilitating injuries and amputated limbs. Doctors put nails in his hips and performed countless surgeries that left him in a full-body cast for months. Richard’s immobility gave him plenty of time to contemplate the meaning of the biblical quote “suffer the little children to come unto me” painted in the hospital auditorium.

As a young man, Richard set out to use what was left of his body to the fullest and explored the world, working as a disc jockey, fishing trawler deckhand, house painter, naval correspondent, aerial photographer, private investigator, foreign journalist, and bartender.

In the book, he chronicles a lifetime of self-described “urgent” choices: shooting police officers in the face with a water gun, doing inebriated wheelies in a parking lot during a drunk-driving-prevention demonstration, applying for seminary school, and eventually providing the funds to help rebuild his mother’s Pentecostal church, the House of Prayer No. 2 in Franklin, Va.

The majority of Richard’s memoir is told in the rarely used second person voice. Using “you” instead of “I” provided Richard distance while he was writing and allowed him to relate more intimate memories from his past with objectivity. In one recollection from his time at the hospital, barbers come to cut the children’s hair:

“And from the deep pockets they pull the pink flasks of cologne and cooling colored water they clap on their hands and rub around your necks and on your faces and through your hair like a blessed baptism that opens your lungs for the first time in forever with its fragrance, remembering you to a world beyond that doesn’t smell like bedpans… dirty sheets, the deathly perfume stench of yourselves rotting in rancid plaster.”

Telling the story this way came naturally to Richard. “The voice of the book and the stance — the material chooses it,” he said.

In addition to giving Richard distance from the material as he wrote, he explained that the second-person voice also invites the reader to become part of the story and gives Richard’s often outrageous tales more credibility.

As he describes in the book, he witnesses an angel passing through his living room on Easter morning. He uses a sword to save a baby from being eaten by a boa constrictor. One night on a boat, Richard writes, a hairless monkey with webbing between its arms and body jumps out of a net that he and a friend had hauled from the bottom of the ocean.

“In the South, when you have some incredible-type story to tell, you always tell it in the second person,” Richard said. “Someone might ask, ‘Mark, how did you end up having your truck upside down in the river?’ and you say, ‘Well you know when you’re coming down the road where the boat ramp is and you have to hook it real hard right and hook it real hard left…’ The ‘you know, you know, you know’ pulls the reader in and makes the reader complicit in the story.”

And so readers are brought along for the ride when Richard starts to make it in the literary world. While digging irrigation ditches after graduating from college, he discovers one of his stories is a finalist in Atlantic Monthly’s American short story contest. A former writing teacher had entered the story without telling him. As the years progress, Richard shapes his career as a writer, profiling Jimmy Carter, writing for Esquire, and signing his first book contract.

Inevitably, even with all the extraordinary steps Richard takes to set himself apart from that special child with bad hips in rural Virginia, he comes right back to where he started. His life-long exploration of faith culminates when he experiences the absolute power of the spirit in a pew at the newly-rebuilt House of Prayer No. 2.

Today, Richard lives in L.A. with his wife and three sons. He is the author of two short story collections, The Ice at the Bottom of the World (Anchor, 1991) and Charity (Anchor, 1999), and the novel Fishboy (Anchor, 1994) as well as the screenwriter for the film Stop-Loss (2008). As a lecturer in the MPW Program, Richard holds fiction-writing workshops, and in addition to teaching, writes for two television shows and numerous publications.

The 2012 Pushcart Prize is the second he has won — he received the first in 1989 for his short story “Happiness of the Garden Variety.” House of Prayer No. 2 was selected by The New Yorker as the June book club pick and has received rave reviews in numerous outlets including The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times.

In her New York Times review, Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum writes about her experience reading the book’s finale: “I felt a shiver pass through my body, and suddenly the memoir’s reticence, its desultory movement, its use of second person, revealed their purpose to me. To understand the mystery of faith, you cannot be told it; you must experience it yourself.”