Explosives, Black Holes and Dr. Who

Nick Warner leans forward in his desk chair, his arms outstretched, hands cupping the air in front of him as if protecting a small flame.

“When I was 15, I had something explode right here,” he says.

For Warner, USC College professor of physics and astronomy, and mathematics, hands-on science is more than just a phrase.

In this case, his hands took the brunt of an unexpected detonation between red phosphorous and potassium chlorate that he had combined in a matchbox.

The resulting sound and shockwaves from the blast rendered him partially deaf for a few days and wreaked havoc upon his hands and arms.

“My hands felt like a stampede of cattle had gone across them,” Warner says.

Spending 10 years of his childhood in the Australian bush provided lots of space to learn about all the wonderful things he could do with his hands, and what not to do. “Sometimes I’m amazed I didn’t hurt myself more,” he says.

But when asked what first interested him in science, it’s exactly these experiences that swayed him — the physical, no-holds-barred, question-driven curiosity of a young boy with a free afternoon and a chemistry set. “One of those real chemistry sets,” he says. “I couldn’t quite make gun powder at first, but it gave me a good start in that direction.”

Warner recalls creating and setting off bombs and missiles with his two brothers, and occasionally with the help of his engineer father, who once helped the boys build a rocket-powered plane. “Of course, we didn’t tell him we were just going to shoot it down,” Warner says, laughing.

Watching Warner describe these first forays into scientific experiments — What happens if I set this on fire? — is like watching him as a child. His eyes widen, he grins, he gesticulates wildly at times. He’s in love with science.

In his down-time from blowing things up, he watched television and idolized Dr. Who, the time-traveling main character of the namesake British television series.

“I wanted to be Dr. Who,” Warner says. “I wanted to build a time machine, and it certainly shaped my career.”

Although he didn’t build a time machine, the real outcome isn’t so different. “I studied Einstein’s theory of relativity, space and time; I got to work with Stephen Hawking, and I work on the quantum structure of black holes,” he says. “What could be better?”

Hawking, the renowned theoretical physicist, was Warner’s thesis adviser at the University of Cambridge, where Warner earned his Ph.D. in physics and mathematics in 1982. The two men have remained in touch through the years, and Warner’s influence was instrumental in Hawking’s decision to give his sold-out black hole lecture at USC in March 2009 as part of The College Commons event series.

Before coming to the College in 1990, Warner taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has also served as a researcher at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Switzerland.

His current research focuses on trying to resolve two established yet conflicting theories in physics — general relativity and quantum mechanics. The best setting to understand these issues, he says, is a black hole, where matter is being reduced to its most fundamental constituents. He applies the newer and still-developing string theory to better understand how to balance the two conflicting theories and discover insights into the nature of black holes.

“The work I’m doing is fundamentally curiosity-driven,” Warner says. “How do we re-model or understand a black hole and its interior structure and the whole nature of space and time using quantum mechanics and string theory?”

Warner admits that, at the end of the day, the driving force behind his research is always the same basic idea. “I just want to know the answer,” he says. “I have since I was about 7 years old.”

Warner conveys the same message to students in his general education astronomy class, “The Universe,” which he has been teaching for 15 years. One of his goals is to help his students appreciate that science at its heart is question-driven.

And the subject matter he teaches fits right in. “Astronomy is the quintessential basic science,” he says, “one whose primary motivating element is simply that you want to know the answer.”

Warner hopes to teach a broad range of science through the subject of astronomy. He cites planetary atmosphere as a good example of how one topic can bring many other disciplines together: The class might touch upon a planet’s gravity, temperature, chemical composition, the planet’s past and future, and then segue into global warming.

“It gives me a springboard to teach them that science is not this compartmentalized thing,” he says. “It’s much more interdisciplinary.”

These classes represent a broad spectrum of the entire USC community, with student majors ranging from business to music. Although the majority of his students are not going to be scientists, Warner believes, at some point in their lives they will be presented with scientific arguments, and will need to be able to evaluate them.

“A lot of science is just common sense. In Australia, you don’t put your hand where you can’t see it, because there are poisonous spiders,” Warner says. “There are certain actions of survival, and you try and teach students a skill set by which they can look at things and wonder: Is this nonsense? Does this feel right?”

His efforts to instill an appreciation for scientific methods and subjects are more than welcomed by his students.

Freshman history major Erica Robles is considering adding a minor in astronomy as a result of taking Warner’s course in Fall 2009. “Professor Warner’s class was an eye-opening experience for me,” she said. “Through the lecture and the accompanying lab we covered an immense range of material relevant to class and to life.”

Senior sociology major Drew Livingston was a student in Warner’s Spring 2009 class, and remembers his professor’s energy and devotion.

“Few educators literally break a sweat sprinting between chalkboards writing out mathematical equations,” Livingston said. “The fact that he could be so excited about teaching an introductory astronomy class, one he has undoubtedly taught many times over, showed that he really cares not only about the subject matter, but about our learning.”

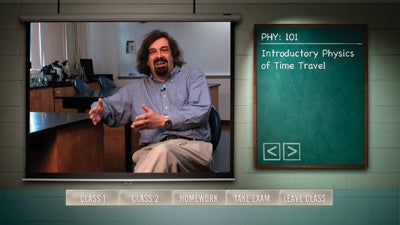

Nick Warner (left), and his USC College physics colleague Clifford Johnson, discuss theories of time and space in “Phy 101: Introductory Physics of Time Travel” on the Lost Season 5 DVD extra “Lost University.” Warner is often contacted by the entertainment industry to lend his expertise to various projects. Photo courtesy of Buena Vista Home Entertainment and Lost Season 5 Blu-ray™ Disc. © ABC Studios.

USC College is not the only university setting where Warner shares the joy of science. Fans of the ABC series Lost can watch Warner, as well as his College physics colleague Clifford Johnson, on the Season 5 DVD extra “Lost University.” In the feature, the two professors, as well as California Institute of Technology physics professor Sean Carroll, talk about the theories of time and space in “Phy 101: Introductory Physics of Time Travel.”

“It’s an audience of millions,” Warner says. “Not all will watch the extras, but some will, and the ones who will have a predisposition to be interested in scientific things.”

“Also,” he adds, “as a recruitment tool to USC, it was a no-brainer!”

Warner is often contacted by the entertainment industry to lend his expertise to various projects. One of his first was the 1985 PBS series Creation of the Universe, which was filmed while he was a postdoctoral scholar at CalTech. Among other contributions, he was a panel member at the 2008 Sloan Film Summit “From Geek to Chic,” was involved in a museum design in Taiwan, and is currently working with space artist Adolf Schaller on a documentary about black holes. “Any time an opportunity comes up, I try to participate,” Warner says.

His requests from the entertainment world have doubled since the National Academy of Sciences created the Science and Entertainment Exchange. This program connects industry representatives with scientists when an expert opinion is needed.

But before Warner gets involved in a script or documentary, he asks himself, “Is it going to make me look like an idiot? Will it have a net positive benefit for me, my field and for USC?”

If the answers are “no” and “yes,” not the other way around, Warner will devote his time to a project. The commitment is worthwhile because it allows him to simply get people excited about science. He also wants to help the entertainment industry create scientist characters who are portrayed correctly and shown as positive role models.

“One of my pet peeves is scientists who turn up on TV wearing white lab coats, with German accents,” Warner says.

Real scientists aren’t like that. In many ways, Warner says, they’re just like everybody else, except they have a different way of analyzing things.

“Scientists have all the wonderful emotional and irrational behaviors that come with being fully human,” he says. “But if you engage them as scientists, you usually get a far more clinical or analytical response, even in very emotional circumstances. This can create these incredible dissonances, which make for interesting storytelling.”

Warner notes that television has recently changed the public perception of scientists in a positive way. In the ’70s and ’80s, there were shows like Star Trek, “where the scientist was the guy with the funny ears who didn’t like women” and other sci-fi shows that portrayed scientists as geeky, often-ignored sidekicks who weren’t the focus of the plot.

Today, House, Bones, CSI and Numb3rs are driven by science and have scientists as main characters. “TV has really embraced science,” Warner says. “You want people to see science as a really neat and cool thing to do. Anything that does this is brilliant, as far as I’m concerned.”

According to Warner, being curious, asking questions, and taking pleasure in simply knowing an answer is what science is all about. “Little kids get that immediately, mucking around with stuff to figure out how it works,” he says.

“But somewhere along the line, we tend to lose that,” Warner says. “It often has to do with the fact that we have to earn a living. Somewhere, somehow, that joy can get lost.”

Warner’s goal is to rekindle that joy, one student and television viewer at a time.

Read more articles from USC College Magazine’s Spring/Summer 2010 issue.