The rise of filmmaking in late 1800s Paris draws crowds in the City of Lights and the City of Angels

The big picture:

- Before Hollywood, Paris dominated filmmaking.

- The earliest films captured everyday scenes of life, such as workers leaving a factory.

- Professor of History and Art History Vanessa Schwartz’s exhibit showcases the artistic and technological innovations of 19th-century Paris that fueled the modern film industry.

- Schwartz will take students to Paris during a Maymester course centered on the exhibit.

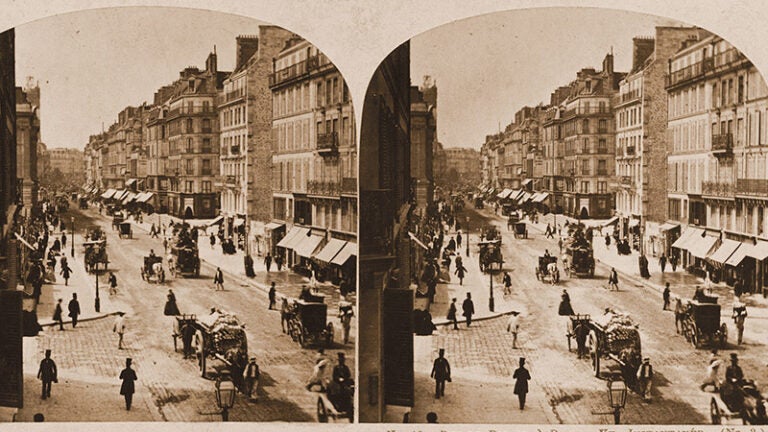

Impressionism and realism. The moving pictures of the Lumière brothers. Even the Eiffel tower. In the late 19th century, Paris became the center of artistic and technological movements that were shaking up traditional forms of art and aesthetics. With a public hungry for new visual spectacles, the city also soon became the cinema capital of the world.

“Ninety percent of movies that circulated the globe before 1914 were made in France or by French companies in America,” says Vanessa Schwartz, professor of history and art history at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and director of USC’s Visual Studies Research Institute. “France played a disproportionate role in cinema production during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

In an exhibit she helped curate for the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Schwartz tells the story of this pre-Hollywood cinematic history through posters, photographs, visual instruments, paintings and sculptures highlighting how cinema arose from this atmosphere of scientific and aesthetic change.

The exhibit wrapped up in Paris in January 2022 and will be revived, in a different form, at LACMA.

“The exhibit is about the relationship of the many visual arts to the origins of the movies in the late 19th century, but there’s a slight difference in emphasis between the French and the American exhibits,” Schwartz says.

In France, she explains, the show looks at more formal developments between the arts, but in L.A. it will examine how the social and cultural history of Paris contributed to changes that defined the modern city: an emphasis on the circulation of people and goods, greater visual orientation of the built environment, and the democratization of access to culture, making possible new forms of culture for the masses.

France aimed to be seen as a world power, as this poster titled “Capital of the Civilized World – Expo Paris 1900” indicates.

Schwartz will also be teaching a Maymester based on her exhibit this spring. “Paris, Cinema and the Invention of Modern Life” (AHIS 499) will begin in L.A., where the students will spend two weeks studying the show at LACMA and how it was put together. From there they travel to Paris to get a behind-the-scenes look at the creation of the exhibit and the items in the collection at the Musée d’Orsay.

Modern arts and sciences

Cinema in Paris didn’t start with the invention of moving images, or even photography. In the 1840s, realist painters like Gustave Courbet depicted ordinary people at work or talking outdoors, a sharp break from the massive canvases of romantic Eugène Delacroix or neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David, which often depicted dramatized historical moments and scenes from mythology.

A few decades later, impressionist painters sought to emphasize visual elements that pointed to the nature of modern life, experimenting with color and light. Meanwhile, photography was quickly becoming industrialized and commercialized, with mass production of the necessary chemicals and paper starting in the last third of the 19th century.

The French government encouraged the development of these and other art forms as a way of creating a shared culture among its populace, Schwartz says.

“France learned early that art could not be used solely for propaganda but also could embody the broader will of the people. Culture is one of the key dimensions in which a general public is created, and as a cultural historian, I’m interested in how culture creates national identity while also promoting change beyond political borders,” she explains.

Technologically, France was positioning itself as a center for engineering and innovation, as well. Emperor Napoleon III invested heavily in the country’s industrialization during the mid-19th century, and he wanted to boost France’s reputation as a modern world power. Paris hosted five world’s fairs in the 19th century alone, with the 1889 event delivering the unquestionable symbol of the city’s engineering and construction might, the Eiffel Tower.

“For these fairs, Paris worked on making its city more visible, easier to get around in, visually memorable. That, too, was an aspect of modernization,” Schwartz says.

More than 50 million people from all over the world visited the 1900 world’s fair — a number greater than the entire population of France at that point. Paris was making its mark on the world.

The early days of film

The first moving pictures, a program of 10 films of less than a minute each that included mundane scenes such as workers leaving a factory, were shown commercially in Paris in December 1895. The films were made by the Lumière brothers, who, along with Léon Gaumont, Alice Guy, Charles Pathé and Georges Méliès (whose classic A Trip to the Moonis still considered one of history’s greatest films), dominated early cinema production.

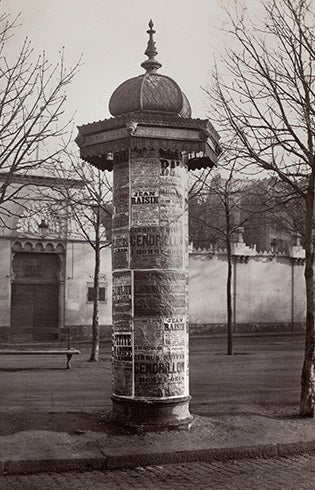

The Morris column was first seen in Paris in 1868 and often featured ads for films and other spectacles.

At only a minute or two long, the first films were more technological achievements than anything else, Schwartz explains. However, Schwartz notes that there was a desire in these early French movies to capture life and its dramas, especially in an environment of dynamic change.

The documentation was not limited to France, either, she adds. French filmmakers set out to capture the whole world on film.

“The world was changing quickly, and film was also a way to capture what was going to be lost. Filmmakers wanted to capture what life was like before people around the world became what the filmmakers envisioned — Western consumers,” she explains.

But these early slice-of-life films were more of a sideshow novelty than a main event, Schwartz adds. They were shown at fairgrounds and in music halls, during carnivals or vaudeville shows.

“There’s nothing inevitable about what film would become,” Schwartz explains. “It doesn’t kill all the other art forms when it’s born — at the start it’s not clear that cinema could ever stand alone.”

It wasn’t until theaters designed specifically to show movies were built, and film editing and technological developments allowed for the creation of longer, narrative stories with scene and set changes, that film became a recognized as an art form and entertainment.

As filmmaking evolved into longer-form storytelling, Los Angeles, with its abundant natural light and plentiful, cheap land, took over from Paris as the center of the industry. But Schwartz says that she hopes the students in her Maymester course will understand how “before Hollywood, there was Paris.”

“The culture in Paris was that of new art forms, as well as the technology that builds the largest tower in the world in two years,” she says. “That tribute to engineering and technology — that is the Paris I want them to understand.”