Aaron Rodgers dropped the ball on critical thinking – with a little practice you can do better

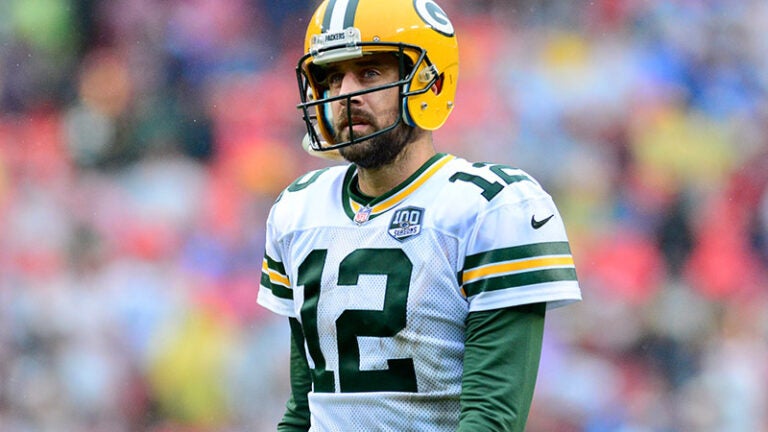

It was hard to miss the news about Green Bay Packers’ quarterback Aaron Rodgers testing positive for COVID-19 on Nov. 3. Like the vast majority of people currently catching — and dying from — the coronavirus, he was unvaccinated.

A few days after his diagnosis, Rodgers took to the airwaves to offer a smorgasbord of pandemic misinformation and conspiracy theories in defense of his decision to skip the COVID-19 vaccine.

Having listened to many an interview with Rodgers, I found it totally predictable that he began his comments by asserting, “I’m not, you know, some sort of anti-vax, flat-earther.”

But as someone who does research on how people think and decide, it’s what Rodgers said next that caused me to lean in: “I am somebody who’s a critical thinker.”

Critical thinker? The fact is, research on the link between critical thinking ability and behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that Rodgers is the opposite.

For scientists like me whose job it is to unravel how people instinctively make choices, and then to help them make better ones, critical thinking isn’t just a slogan used to score points. It’s not some after-the-fact justification someone makes to convince others — or themselves — that their opinions or behaviors are sound.

Instead, critical thinking is a pattern of behaviors that happen before someone makes a judgment, like coming to the conclusion that something is risky. Likewise, critical thinking comes before making a decision, like choosing to avoid something judged to be too risky for comfort.

Here’s what it really takes to be a critical thinker.

Three ingredients for critical thinking

Critical thinking as a precursor to sound judgments and decisions involves three related elements that are accessible to almost anyone.

First, critical thinking means being able to recognize that there are situations where you must balance your instinctive reactions to what’s going on around you, based on emotions like fear and desire, with the need for a heavier psychological lift. In these cases, it’s crucial to take note of conflicting objectives and make difficult trade-offs.

Take the pandemic, which, thanks to the arrival of new variants like omicron, has gone into overtime. You may have a strong desire to live your “normal” life as you knew it before COVID-19 started to spread; at the same time, you probably want to keep those around you safe and secure. Knowing where to draw the line between personal comfort and the well-being of those around you means putting your emotions to the side and diving into data so you can better understand the broader consequences of your intended actions.

Second, critical thinking means following some basic principles when you search for and use information. You must be open to and consider more than one solution to a problem, without ignoring or dismissing evidence that goes against your initial beliefs. And you must be willing to change your mind and your behavior in response to new information or insights.

Last, critical thinking means recognizing when you are out of your depth and then looking to legitimate experts for help. In other words, critical thinkers understand when it’s time to outsource critical thinking to others.

But this raises an important question: How do you figure out who is an actual expert? Critical thinkers answer this question by not just looking at someone’s stature or credentials. They also assess potential experts’ behaviors with respect to the first two elements of critical thinking. How good is the expert at balancing instinct with the need for more in-depth analysis? And does the expert follow the basic principles that should govern the search for and use of information?

Everyone loses when critical thinking is sidelined

Consider the results of a recent study conducted during what scientists around the world agree is a serious public health crisis. In it, my colleagues and I found that people in the U.S. who score high on a scale used to measure critical thinking ability judge COVID-19 to pose a real and significant risk to public health. They also placed greater trust in legitimate public health experts, and — importantly — behaved in a manner that is more consistent with pandemic risk management strategies recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Judging by his behavior and statements, Aaron Rodgers wouldn’t have belonged in this group. Indeed, Rodgers’ own comments suggest he fumbled his way through the three elements of critical thinking.

In spite of his claim that his decision to remain unvaccinated involved “a lot of time, energy and research,” it seems he neither understood nor weighed the trade-off between the exceedingly slim chance of becoming sick from one of the available vaccines versus the much higher probability of becoming sick — or making others sick — from COVID-19.

And historically, Rodgers hasn’t been shy about dismissing viewpoints that run counter to his own. Boasting about his COVID-19 infection, Rodgers confessed as much when he said, “I march to the beat of my own drum.”

Finally his success rate when it comes to handing off critical thinking to others is lousy. On COVID-19, he follows the advice of pseudo-experts like Joe Rogan over that of actual medical experts and has chosen to subject himself to a demonstrably dangerous drug, ivermectin, instead of a safe and effective vaccine.

Unfortunately, Aaron Rodgers is far from alone when it comes to poor critical thinking. And, making matters worse, the implications of uncritical thinking extend well beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Indeed, the poster child for an absence of critical thinking is the political divide in the U.S. From Main Street America to the U.S. Capitol, I’d argue that nothing says my-way-or-the-highway like the inflexible tribalism that has infected important policy issues ranging from inequality and climate change to guns and health care. Balancing fast-acting emotion with the slow burn of analysis, a willingness to change your mind and compromise, and the courage to admit you are not an expert — and to trust those who are — seem as far away in politics today as they have been in decades.

Training camp for critical thinking

On the bright side, and with a little practice, people can learn to think critically. Unlike other tasks that require highly specialized skills — like playing the position of quarterback in the NFL — critical thinking is well within the reach of nearly anyone willing to put in the reps.

Studies show, for example, that critical thinking can be activated in the moment just before certain judgments or choices need to be made. Researchers also know that the basic principles of critical thinking can be taught, even to young children and adolescents. And, for complicated judgments and choices, people can take advantage of decision-support tools that help them clarify their objectives, consider relevant information, evaluate a wide range of options and understand the compromises that come with choosing one possibility over another.

Deploying the skills of critical thinking ultimately requires one more important ingredient, though, and this one can’t easily be taught: courage. It takes courage to break from your closely held opinions and, especially, from the relative sanctuary offered by your social or political circle. And it takes courage to publicly change your mind and your behavior.

But here too there’s a bright side. Changing your mind and behavior because you thought critically about something doesn’t mean that your earlier opinions and behaviors were a mistake. On the contrary, it’s a public display that you learned something important and new. And that, at least as much as success on the frozen tundra of Rodgers’ home field in Green Bay, is worthy of respect and admiration.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]![]()

Joe Árvai, Dana and David Dornsife Professor of Psychology and Director of the Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.