Alumnus writes a foundational history of Thai Americans and appears on ‘Taste the Nation’

Tucked into the red-chalk desert of Nevada lies one of the largest Thai communities in the United States. Las Vegas is home to over 5,000 Thai Americans and boasts some of the best Thai food in the country.

This renowned culinary community was recently highlighted on Padma Lakshmi’s Hulu show Taste the Nation, with alumnus Mark Padoongpatt, associate professor of Asian and Asian American studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, on hand to fill her in on the history of Thailand’s most famous dish: pad Thai.

There’s probably no better source for Thai American history than Padoongpatt, who graduated from the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences in 2011 with a Ph.D. in American studies and ethnicity. His book Flavors of Empire: Food and the Making of Thai America (University of California Press, 2017) offers a rarely seen historical accounting of Thai Americans.

As he and Lakshmi dig into a Styrofoam take-out container of the savory noodles, Padoongpatt clears up common misconceptions about the meal. It’s not a particularly traditional Thai dish, he explained, but one created in the 1930s by Thailand’s Prime Minister to help form a national identity after the Siamese revolution.

The dish was accessible enough to American palates that early Thai immigrants, arriving in the 1980s and establishing restaurants, could satisfy locals while introducing a new cuisine – hence, its ubiquity.

And are chopsticks the usual utensil for the meal? Nope, says Padoongpatt. Thai restauranteurs hand those out to satisfy westerners’ expectation of chopsticks when eating an Asian meal, thanks to the earlier proliferation of Chinese eateries.

Consciousness raising

Growing up, Padoongpatt had little interest in talking about Thai food. It was the only thing people seemed to known about his culture, and this one-dimensional understanding of Thai Americans was dissatisfying.

He was much more enchanted by basketball, which he’d started playing in 7th grade. “I felt like I wasn’t American enough for all of my friends, since I was Asian American. I’m also dark-skinned, so I felt too dark for Thai people,” Padoongpatt recounts. He felt a kinship with the dazzling Black players of the Lakers. “I identified with the Blackness there; it was something to identify with that felt positive as a dark-skinned person,” he says.

Mark Padoongpatt was born just blocks from Thai Town in Hollywood. (Photos courtesy: Mark Padoongpatt)

Padoongpatt’s parents emigrated from Thailand to Los Angeles in the 1970s, meeting and marrying in the U.S. The family lived in the working-class communities of Pacoima and Northridge, in diverse neighborhoods of Latino, Black and Asian families.

It was a bit of an adjustment then, when Padoongpatt arrived at the University of Oregon for his freshman year. He’d received a scholarship to attend and was excited about the campus’ idyllic charm, lined with broad, leafy trees and studded with distinguished brick buildings. It was also a predominantly white campus which, at first, felt like something he’d have to just blend in with.

“The first couple of weeks I was there, I thought, ‘This is the dominant culture, I have to figure this out,’” Padoongpatt says. He threw himself into socializing, attending football games and welcome events.

An experience at a new friend’s house over Thanksgiving, as the only person of color, gave him pause: “I remember having this epiphany. I was really gravitating towards whiteness, and I remembered this is just not who I am.”

He branched out and found community in Asian American student organizations and the Black Student Union Multicultural Center. Ethnic studies classes helped him hone in on his choice of major. “It was kind of a blessing. I think that if I had gone to a school with more students of color I don’t know if that consciousness would have happened to me,” he says.

Past Pad Thai

By graduation, Padoongpatt was already determined to write a history of Thai Americans. A formative class on Asian American communities made him consider how he could help his own. “At that moment in junior year, I was set on going to graduate school to write that history,” explains Padoongpatt.

When it came to selecting a graduate school, USC Dornsife felt like the clear choice. His dissertation would focus primarily on Los Angeles, which hosted the largest Thai community outside Thailand. Padoongpatt himself was born in Hollywood, just steps from the vibrant Thai Town hub.

He was still convinced he wanted to avoid the subject of Thai food, however. “I was actually kind of opposed to writing about food,” says Padoongpatt. “I felt like all the attention was on food and not enough attention was on Thai people. Food was a distraction. We forgot about issues like immigration or labor exploitation.”

Once he began his research however, he found that food was actually an excellent conduit to the histories he was eager to uncover.

“Many of the issues that I cared about in the Thai community were linked to food. There wasn’t a lot of documentation on the Thai experience, and so I discovered that most of the stuff in the historical record was somehow connected to food, like cookbooks or reporters interviewing Thai restaurant owners. So, it was having to go through food to get the stories I wanted anyways,” says Padoongpatt.

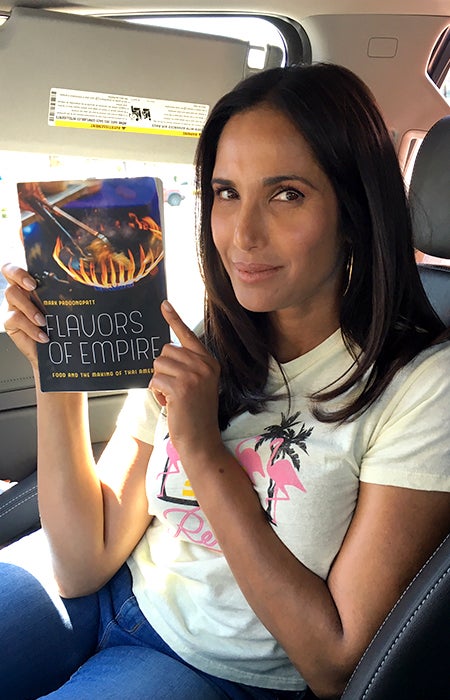

Lakshmi pictured holding Padoongpatt’s book Flavors of Empire.

Pioneering history

The book that developed out of his thesis broke new ground by exploring the formation of Thai American immigrant communities in the United States starting with the Cold War, a subject rarely touched upon. The Thai American experience is still frequently passed over — PBS’ recent documentary on Asian Americans failed to include Thai Americans at all.

Since his book’s publication, Padoongpatt has, rather ironically, become somewhat of a spokesperson for Thai food history. Public radio interviews with Evan Kleiman of Good Food and Francis Lam of The Splendid Table, which led him to Lakshmi and her show, have called on him for input on Thai food culture. He’s grown comfortable with this association, however, as he now views it as a conduit to bigger conversations.

“Padma read my book and she said, ‘I feel like your book is using food to talk about the Thai community,’ which is exactly right,” says Padoongpatt. “We have this kinship because she’s using her show and food as a way to really talk about immigrant communities.”

For those curious to try out the Las Vegas Thai food featured on Lakshmi’s show, Padoongpatt has a suggestion: Avoid the city’s center. Instead, drive a few miles into its suburban outskirts. It’s there that industrious Thai immigrants have set up shop in strip malls, as they have done for so many years in so many American cities, sharing their cuisine with their new countrymen.