The fabled Florentine Diamond takes center stage in tale of family and fate

People love a good mystery — especially when it’s unsolved. Countless books, documentaries, television shows and movies have been devoted to the uncertain fates of the Romanovs, Amelia Earhart and Jimmy Hoffa.

But the Florentine Diamond?

Despite having all the right elements for a juicy historical mystery — a stolen jewel, the flight of an emperor into exile and even possible links between the gem and Marie Antoinette — the diamond has received scant attention in popular culture. So, for Amy Meyerson, associate professor (teaching) of writing at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, the tale was the perfect one on which to base her new novel, The Imperfects (Park Row Books), which debuted in May.

The Imperfects sketches out a possible fate for the diamond and intertwines it with the story of a fictional American family, the Millers, and its members’ complicated relationships with both each other and their shared past. When the family matriarch dies, leaving her granddaughter a large yellow diamond, her descendants trace the diamond’s history, hopping from Los Angeles to Philadelphia to Austria in the process.

“I knew I wanted to write about the Florentine Diamond, and I just followed the research. I had few expectations in terms of where it was going. I didn’t want to write straight historical fiction, with a present and a past storyline. I wanted to write about what we can tell about the past based on artifacts, and also what is lost about that past. And family, too. Sometimes we don’t develop an interest in family history until it’s too late,” Meyerson explained.

The diamond

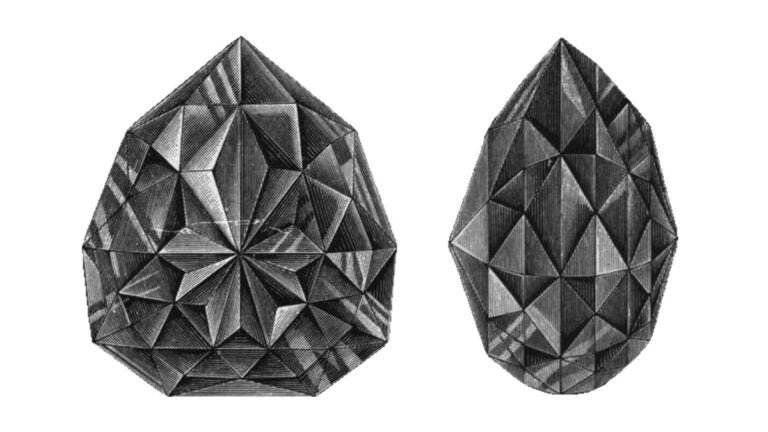

At 137.27 metric carats, the Florentine Diamond was enormous. Its story begins with the legend that Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, was wearing the diamond when he was killed in battle in 1467. A commoner is said to have filched it from the dead duke and, assuming it was a fake, sold it for a pittance.

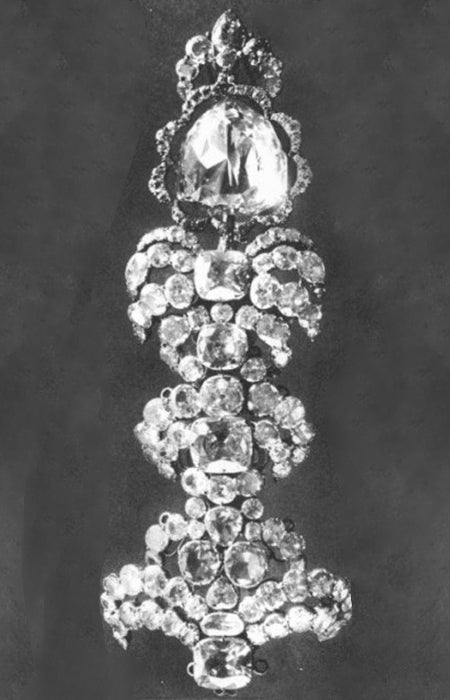

This photo, taken between 1870 and 1900, shows the Florentine Diamond set as cap decoration. (Image Source: Wiki Commons.)

Its first documented owner was Ferdinand II (1610 – 1670), the grand duke of Tuscany and a member of the powerful Medici family. The diamond remained within the family until it was transferred to the Habsburgs through Francis of Lorraine, who married Maria Theresa von Habsburg in 1737. (The couple would become parents of the future Queen of France Marie Antoinette.) By 1743, the diamond had become part of the Austrian crown jewels, where it remained until the Austrian Empire fell after World War I. In 1918 former Emperor Charles I sent the stone, along with many other jewels, to Switzerland, where he was going into exile; however, the diamond was stolen before he arrived, and its fate remains unknown.

“What drew me to this diamond is the uncertainty about how it went missing,” Meyerson explained. “We know when it went missing — it was last seen in 1918. And there’s a lot of uncertainty about the diamond all around. There were rumors that the Hapsburgs thought it was cursed, and that Marie Antoinette had worn it. Jewelry historians didn’t know about the stone either. For something with so much rich history it seemed unknown.”

The kindness of experts

The diamond’s fate leaves plenty of room for imagination, but extensive research was still necessary to write the book. Meyerson focused on investigating three topics: Austrian history, including the Habsburgs, World War I and World War II; gemology; and cultural heritage law. Her first step was library research, followed by extensive conversations with experts in a wide variety of fields.

“I read enough to know what preliminary questions to ask,” Meyerson said. “Then I asked experts and they guided me to more books and research materials, or they guided me to other people. Then I repeated the process. I talked to lawyers who specialize in cultural heritage law. I talked to an FBI agent who started an art crime task force in the 1980s. I spoke with the librarian at the Gemological Institute of America.”

Although Meyerson doesn’t know what happened to the diamond, her research has suggested some likely possibilities.

“It’s almost definitely been recut. Stolen stones are nearly always recut to mask their identity,” she notes. In Geneva in 1981, a 70-something carat diamond was put up for auction. Given how few stones can accommodate that sort of cut, it is likely that auctioned stone had once been part of the Florentine Diamond, she explains.

Who gets to tell a story?

Beneath the novel’s tale of the diamond and the family that finds itself involved in its story is a deeper exploration of the past and how its stories should be told.

Author and writing professor Amy Meyerson. (Photo: Courtesy of Amy Meyerson.)

There’s a point in The Imperfects when one of the main characters, Jake, is confronted by his girlfriend, Kristi, about some abandoned screenplays he had written based on her Chinese mother’s experience immigrating to the United States. It was a deeply personal experience, Kristi explains, that her mother never gave him permission to write about.

Meyerson said she made the character of Jake a screenwriter to address the question of who gets to tell what stories, and the scene exemplifies the difficult balancing act writers face when telling fictional narratives that are based on real people from another culture.

Moreover, the scene has some basis in reality. The character of Kristi’s mother is based on Meyerson’s brother’s mother-in-law, who is from China.

“I talked to my brother’s wife, whom I’m very close to, and her mom about her story in relation to my book. Her mom’s response was that she was honored to be included. But I intentionally didn’t write that story. I just included some elements, so I didn’t appropriate but just alluded to it,” Meyerson explained.

This caution extended to historical characters, as well.

“I struggled with having the empress Zita as a character. I knew I wanted her to be a character, but there isn’t much written about her in English. When I felt conflicted about that, I spoke to an Austrian historian, and he said the people there don’t have any particular love for her, so I felt a little more settled about my choice of making her an antagonist.”

Meyerson said she makes sure to teach her students about “cultural appreciation versus cultural appropriation,” noting that the former can be achieved when treating a subject with respect and an open mind, as well as the ability to understand why borrowing some subjects is more damaging than borrowing others.

Back to the future

Meyerson said that during her research in Austria, she went to a museum that had empty cases to signify the missing crown jewels of Austria, prompting her to reflect on how the loss of a past can shape history.

“I assumed the cases were empty because the items were on loan. But the historian told me those cases represent the crown jewels the Habsburgs stole. They theoretically belonged not to the family but to the empire. So, the cases will remain empty until the jewels return to Austria. I found it neat they had cases devoted to this history that is still missing. You can create a story not just about artifacts that were left but also their absence,” she explained.

But, despite the intrigue that comes with mysterious disappearances, ultimately people must learn the stories and lessons of their pasts in order to preserve them.

“As my parents become grandparents and they become the older generation, it makes me think about what I asked and what I know,” she said. “They answer questions about the past that I cannot, and I want to make sure I have those answers for my son when he is interested. I feel there is an added responsibility to the past for future generations.”