Finding Faith during captivity: The role of Buddhism in Japanese American internment camps

When 10-year-old Masumi Kimura, who had been born in Madera in California’s San Joaquin Valley, rushes home to her Japanese parents after news breaks of the attack on Pearl Harbor, she finds her father being beaten by men in suits and her mother sitting at the kitchen table, very still, while a man holds a shot gun to her head.

“Even though this little Japanese American girl is only 10, she realizes she needs to step in because her parents speak hardly any English and clearly these men in suits, whom she’d find out momentarily were FBI agents, didn’t speak any Japanese,” says Duncan Williams, a Buddhist priest and professor of religion, East Asian languages and cultures and American studies and ethnicity at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

As she translates, Kimura discovers her father is on an FBI list that requires him to be interrogated in the event of war with Japan because he is a leading board member of the local Buddhist temple.

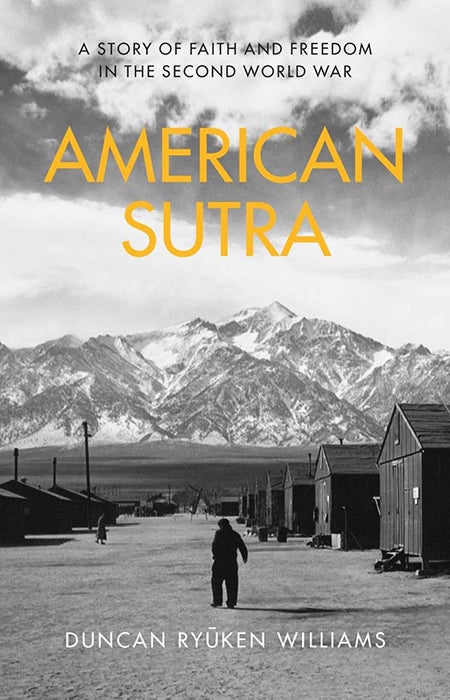

This incident appears in Williams’ best-selling book American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Harvard University Press, 2019). The book explores the role of Buddhism in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The book was inspired by Shinjo Nagatomi’s diary, written during his internment. Nagatomi, a Buddhist priest, was the father of Williams’ mentor, Masatoshi Nagatomi, Harvard’s first professor of Buddhist studies. The diary, which Williams discovered among his mentor’s belongings after his death, was written in Japanese, and Williams translated it for the family at their request 17 years ago.

“That got me started wanting to learn more about what happened to the 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast of the United States, and how they were taken to these remote camps in Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado and Arizona,” Williams says. “What happened to them there and why?”

Although it wasn’t a subject in which Williams had academic training, as he translated the diary, he felt compelled to learn more. Shinjo Nagatomi wrote about the sermons he delivered in the camp on how to deal with dislocation and loss, especially during that first winter and spring, from 1942–43 when many — especially the most vulnerable, the elderly and young babies — didn’t survive.

As a Buddhist priest, Shinjo Nagatomi would perform funerals and try to console the families who, after losing their homes, their jobs, their incomes, their place in society and almost all their worldly belongings, were now losing beloved family members to the harsh conditions in which they were being forced to live.

Singled out

While most historians have argued that it was the racial animosity of that time that put the Japanese American community, and not the German American or Italian American communities, into these camps, Williams’ research showed another significant factor.

American Sutra sheds light on how Japanese Americans fought to defend their faith and preserve religious freedom during one of our country’s darkest hours.

His discovery of declassified memos between President Roosevelt and Attorney General Francis Biddle show that Japanese Americans were singled out for internment because of their religion. Lt. Gen. John DeWitt, who oversaw the internment process, also pointed to the fact that they were majority Buddhists as a factor in his own assessment of why they constituted a threat to national security.

“What I found in my research was that, in addition to race, religion played a very major role in the assessment of U.S. government and army officials about viewing this majority Buddhist community as a threat to national security,” Williams said.

His research also shows that the very thing that put Japanese Americans into these camps — namely their Buddhist faith and affiliation — was also what helped them to survive this supremely difficult time in their lives.

“It was a moment when, in that dislocation and loss, people turned to their faith,” Williams said.

Williams’ book describes how the Japanese Americans selected for internment were given a week to 10 days to disenroll from college or sell their businesses and pack only what they could carry before being taken to remote camps. There, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guard towers, they had to face captivity for an unknown duration.

Williams estimates that more than 1,200 Japanese Americans perished in the camps.

While there were a dozen cases of people shot by guards at the fence line, most deaths were caused by the harsh conditions.

“Unsurprisingly, they put these camps in very remote, primarily desert conditions,” Williams says. “The harsh environment and climatic conditions were hardest on the most vulnerable occupants: namely, newborns and the elderly. Poor nutrition, sanitation and living conditions contributed to illnesses such as influenza and pneumonia.”

Williams translated diaries of those interned in the camps and interviewed more than 100 camp survivors as well as spending several years in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., declassifying documents and exploring additional archives.

The book — a 17-year labor of love — made the Los Angeles Times’ bestseller list for nonfiction for three weeks, peaking at number three. Williams has spoken at almost 50 venues about the book, from the Smithsonian to Yale Law School to Apple.

“It’s been interesting to talk about this history,” he says, “but also to talk about how it relates and connects to some discussions that are happening today around immigration, race and religion and who belongs in America.”

Williams says what he most wants readers to take away from his book is this idea that people can be both Buddhist and American at the same time.

Two thirds of that 120,000-person community were American citizens, yet they didn’t receive due process, Williams notes.

“With any one of these constitutional promises of equality of the law, due process or religious freedom — these really foundational American values — there are only words on a piece of paper, unless somebody embodies it and actualizes it.”

A third space

A Buddhist funeral takes place in 1943 at Heart Mountain Camp, a Japanese American internment camp in Wyoming. (Photo: Courtesy of Duncan Williams.)

Born in Tokyo to a Japanese mother and a British father, Williams was raised almost entirely in Japan until he was 17, when he moved to the U.S. for college.

He joined USC Dornsife in 2011 from the University of California, Berkeley. At USC Dornsife, he chaired the School of Religion, creating a new Ph.D. program to rival the top institutions in the country. He also created the Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Cultures, of which he’s the director.

In addition to his British-sounding name, Williams says he doesn’t look particularly Japanese and wasn’t considered to be fully Japanese while growing up.

“And of course, when I went to the U.K., it was very clear, I couldn’t pass as 100 percent British either,” he says. “So, I felt this not quite belonging in either place. I think that’s one of the reasons I came to America. It was this third space, where I could explore and imagine what it might mean to belong in a different way.”

It’s also one of the reasons he was attracted to Buddhism.

“The Buddha teaches that the self is actually not solid, permanent or autonomous, but rather interdependent, flexible and dynamically changeable. That resonated with my own experience growing up.” Williams was ordained as a Buddhist priest when he was 21 and trained as a monk in Japan. He is currently affiliated with a Japanese American temple in the Little Tokyo district of downtown Los Angeles.

Williams believes his own experiences of growing up not fully belonging drew him to this area of study.

This majority Buddhist community of interned Japanese Americans, despite being told they don’t belong, persisted in their practice of Buddhism, and in so doing, they ironically may manifest a very fundamental American principle about religious freedom, Williams argues.

“That’s what I want readers to take away from American Sutra: Is America fundamentally a white and Christian nation only? Or is it a multi-ethnic and religiously free nation?”