50 years after the first moon landing, USC Dornsife scholars and artists reflect

Astronaut Neil Armstrong’s walk on the moon on July 21, 1969, was a beacon in troubled times.

America was in tumult after World War II. A fiercely oppressed civil rights movement had begun in the ’50s and continued through the ’60s. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. His brother and presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy was killed in Los Angeles in 1968, just a few months after civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. The Vietnam War worsened in 1968, rocking the American military back on its heels after the North Vietnamese army launched the Tet Offensive.

“Amid all the upheaval, Apollo provided a unifying moment for the country,” says Peter Westwick, adjunct (research) professor of history at USC Dornsife.

The moon landing was a respite from all of the tumult. Up until Armstrong, a USC alumnus, stepped off the ladder of Apollo 11 onto the lunar surface, a moonwalk was merely science fiction. But his one small step was watched by millions of people around the world, and it inspired big dreams.

A boy and his dream

Many scientists, engineers and astronauts took their respective paths because of the moon landing. Vahe Peroomian, associate professor of physics and astronomy at USC Dornsife, was just 4 years old at the time, living in Tehran, Iran.

“The Apollo program, the moonshot of my generation, inspired me to earn a Ph.D. in physics and carry out several decades of research in space science, with an ever-increasing passion for teaching,” he wrote in a recent article for the syndicate, The Conversation. “Now, each time I step into my astronomy classroom, it’s my own sense of wonder, the sense of exploration I felt as a child, that I try to instill in my students.”

An illumination

Enrique Martínez Celaya, Provost Professor of Arts and Humanities at USC Dornsife and USC Roski School of Art and Design, is a physicist and an artist. At the time of the moonwalk, he had heard nothing of it. He and his family were living in a small Cuban town, Nueva Paz, near the Caribbean Sea.

Artist, physicist and USC Dornsife faculty member Enrique Martínez Celaya stands next to one of his latest paintings featuring the moon. (Image: Courtesy of Enrique Martínez Celaya.)

“If American triumphs reached the intelligentsia in Habana, they never found their way to us in the countryside,” Martínez Celaya says. “When we left for Spain, I remember looking out the window at the moon, still unreached, and maybe unreachable.”

He says he learned about the moon landing in 1972, three years after the fact, when he and his family were in Madrid. “I learned about it in school, without pictures, so I tried to imagine the two astronauts, whose names I didn’t know, alone up there,” Martínez Celaya says.

Now, years later, the moon is a source of inspiration for a large painting that he is working on at his Culver City, California, studio.

Pie in the sky

Westwick, who specializes in aerospace history, says that although he was an infant at the time of the moonwalk, he became captivated by it later.

“After I studied physics and then took up history of science and technology, it of course became a central episode in what I teach and study,” says Westwick, the editor of an essay collection, Blue Sky Metropolis: The Aerospace Century in Southern California (Huntington Library and University of California Press, 2012). “On a personal level, it is still mind-boggling to me to look up at the moon at night and think about the fact that we delivered human beings to the moon’s surface, and they walked around up there, and then we brought them home.”

Lunar allure

Vanessa Schwartz, professor of history and art history at USC Dornsife, says she recalls that her elementary school was divided into three houses named for the three astronauts on board Apollo 11: Armstrong, (Buzz) Aldrin and (Michael) Collins.

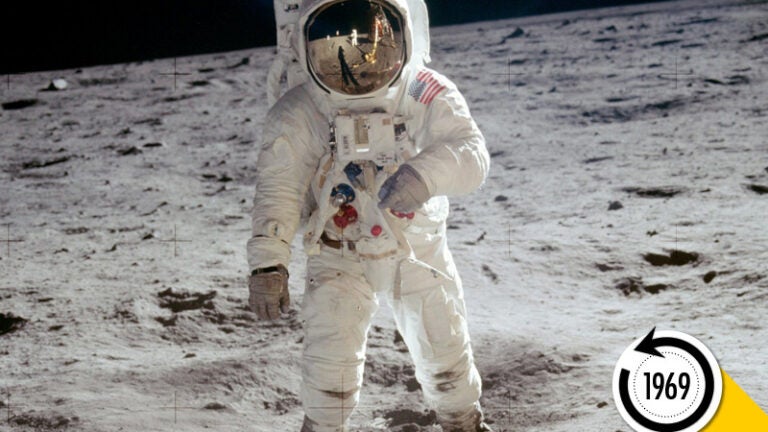

Schwartz, who directs USC Dornsife’s Visual Studies Research Institute and has an upcoming book, Jet Age Aesthetics: The Glamour of Media in Motion (Yale University Press), offered her expertise on the importance of visual culture to the mission. Starting in 1962, NASA had an extended art program that included the likes of Norman Rockwell and Andy Warhol. Some of the most important images from that time were taken by the astronauts themselves, including the iconic photo “Earthrise” by astronaut William Anders in 1968, and Armstrong’s photo of Aldrin in which the mission captain and photographer is also reflected in Aldrin’s helmet visor.

“NASA understood that it wasn’t just about the technological accomplishments and new scientific knowledge. By capturing the beauty of the Earth, the astronauts allowed us to ask profound philosophical questions about human existence.”

Schwartz says that NASA’s vision for Apollo 11, just two years after the Apollo 1 fire in 1967 killed three astronauts, was not simple nationalism. Its optimism had global aspirations. The agency took a big risk by broadcasting the landing live, but it paid off,riveting an estimated 500 million to 600 million viewers globally to their TV sets.

“I think everyone watched Apollo 11 not only for the fear but because such feats generate collective optimism,” Schwartz says. “Many wonder whether it was a foolish spending race in a futile Cold War, but the space program pioneered enormous advances in what are now everyday technologies, such as computer software and satellites.”

She adds: “If we pay careful attention, we can see that the ethos was not about the triumph of science, technology, engineering and math, but rather celebrated the beauty of the relationship between humans and machines.”