Neurobiologists help untangle the brain’s life-support network

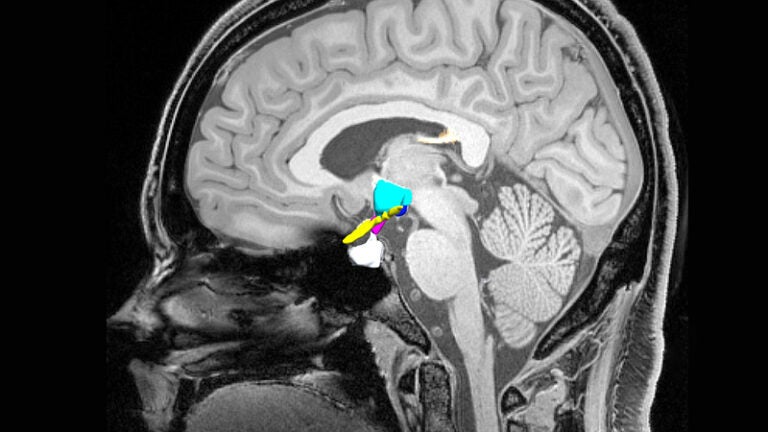

The portion of the brain known as the hypothalamus is small but mighty — it controls fundamental behaviors and physiology that are essential for survival. These include eating and drinking, sexual and defensive behaviors, sleep, and physiological control of things like body temperature, fluid balance and the body’s responses to stress.

The hypothalamus is considered among the most critical parts of the brain, as it supports life in all mammals as well as fish, birds and many other animals.

A USC Dornsife-led study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on March 25, has provided the first global network model — based on a highly detailed network map — of the inner workings of the hypothalamus. The study is part of an ongoing effort to determine the structural organization of the mammalian nervous system, which the scientists refer to as “The Neurome Project.”

Project scientists’ efforts are currently focused on completing a model of the mammalian brain that is based on the connections of its gray matter regions. Eventually, they would like to extend the model to include the connections between the entire nervous system and the body, together called the “neurome.” Such an achievement, combined with network maps for the different types of brain cells, would revolutionize research in a multitude of disciplines, from psychology to medicine.

Thousands of connections

To create the network model of the hypothalamus, the scientists conducted a rigorous analysis of connection data for each of 65 identified hypothalamic regions and spanning 40 years of brain research. Computer analysis of this data revealed a hierarchical organization composed of subnetworks of the 65 regions of the hypothalamus on each side of the brain.

Out of 16,770 possible connections within and between the 65 regions on each side of the hypothalamus, the dataset collated by Hahn and his colleagues indicated that nearly 8,000 of them do exist.

“This shows that the hypothalamus has a remarkably highly connected internal network,” says Joel Hahn, assistant professor (research) of biological sciences at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and the study’s lead author.

The computer analysis of the network also showed that two high-level subnetworks, on each side of the brain, are associated prominently with controlling either behavior or the body’s physiology.

Additionally, the most highly connected regions, or hubs, were in the physiology-related control network. Hahn says this organization suggests that the hypothalamus may prioritize physiological over behavioral control.

“This organization makes sense from a survival standpoint, because behavior depends on an able body,” he says.

Diving down deeper

The scientists also explored the lower-level subnetworks, which revealed novel associations that could be relevant to several diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, and behavioral disorders that impact one or more of the functions in which the hypothalamus plays a central role.

Finally, as they developed the model, the scientists also made another discovery: Transmission of neuronal signals in the hypothalamus appears to be dominated by neuronal inhibition.

The scientists made the discovery as they analyzed genetic markers for inhibitory and excitatory (stimulatory) neurotransmission. First, they developed a map of excitation and inhibition throughout the hypothalamus. Then, they compared the map to the new network model.

They found that neuronal inhibition is most strongly associated with the most highly connected network nodes (hubs) of the hypothalamus. Hahn says this suggests that overall, the hypothalamus is restrained but primed for action. He likens it to water held behind a dam that is released by opening the floodgates.

“We don’t know the functional consequences of this finding,” Hahn says. “But from a mechanistic perspective, removing inhibition from a system that is primed for action achieves results fast. So, it could be beneficial for survival.”

About the study

Other study co-authors were USC Dornsife neurobiologists Larry W. Swanson and Alan G. Watts, as well as Indiana University computational neuroscientist Olaf Sporns.

The study was supported in part by a grant to Swanson and Hahn from the Kavli Foundation, and by a National Institutes of Health grant (R01 N5029728) to Watts.