German documentary taps Peter Mancall for historical perspective on alcohol and drugs

If someone in the 18th century said, “He’s eaten a toad and a half for breakfast,” what were they referring to? Listed in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, this colorful expression is one of no less than 228 popular descriptions of drunkenness used by colonists in North America.

“This is a sign of just how common excessive drinking was in North America during this period,” Peter Mancall, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities and Linda and Harlan Martens Director of the Early Modern Studies Institute, told a German television crew.

The production team had traveled to Los Angeles to interview Mancall, professor of history and anthropology, for Terra X, a weekly documentary series on Germany’s biggest public broadcast station, ZDF. The program attracts around five million viewers.

Mancall was answering questions on the impact of alcohol trade on native cultures in North America — a field in which he has long been a leading expert, having published a book on the subject: Deadly Medicine: Indians and Alcohol in Early America (Cornell University Press, 1995).

“It’s not very easy to find somebody who’s got such a huge knowledge about the subject of early settlers, first colonists and the Native Americans,” said Stephan Arapoyic, a director and producer of the two-part documentary. “There are just a handful, and Peter is one of the historians who’s really into the subject and is really passionate about [it].”

Mancall said he wrote his book to puncture the stereotype of the drunken Indian and the now discredited argument of genetic bias. “To me the most important thing that came out of my research was to see those powerful voices from Indian Country protesting the alcohol trade, and we see that throughout the records in the 17th and 18th centuries.”

A new relationship with alcohol

Mancall began the interview by comparing Native Americans’ radically different relationship with alcohol to that of the European settlers. Before the Europeans’ arrival in 1492, the vast majority of Native Americans had no experience with alcohol, he said, although there were some exceptions.

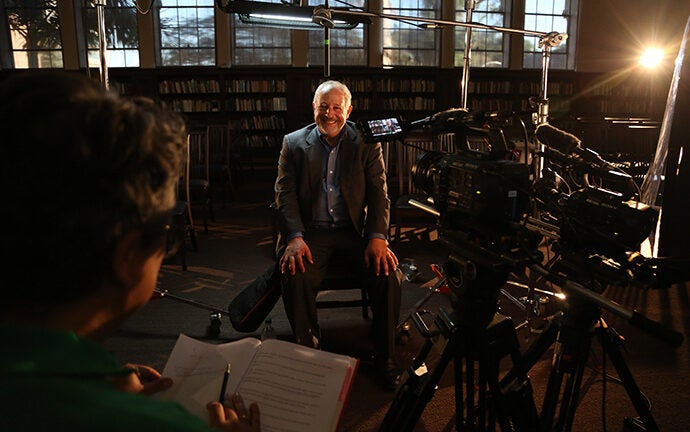

Peter Mancall answers questions about his research on Native Americans and alcohol in early America for a German documentary.

“In the South West of what is now the U.S. and in Mexico, they did drink fermented sap from local plants, but all drinking by indigenous peoples was linked to religious rituals,” he said. “There was no evidence of casual drinking, toasting or after-dinner drinking.” Instead, Mancall said, some native peoples tended to confine their drinking to one particular day in the belief that it would bring a desired event, like rainfall.

“However, in Eastern North America there was no alcoholic beverage, so the people in North America, who bore the brunt of the arrival of Europeans, had no prior exposure to alcohol at all,” he said.

Among the European colonists, the picture was very different. Europeans had been fermenting alcohol for centuries and in many areas beer was considered safer to drink than water. People began drinking at age 15 or 16, Mancall said.

“Drunkenness was frowned upon, but not drinking,” he explained. “In the 17th century, people consumed vast quantities of alcohol, doing the equivalent of seven shots of rum a day and leading perfectly normal lives.”

A sinister aid for trade relations

Mancall gave his German interviewers insights on the important role alcohol played in the fur trade. When Europeans arrived in the Americas they wanted Native American trading partners so they could obtain furs and deerskins. Native Americans were eager to oblige in exchange for shirts, mirrors, metal tools, and possibly weapons.

After 1650, when colonial traders began bringing rum to trading sessions, Native Americans were largely repulsed by their first taste of alcohol, comparing wine to blood. However, some developed a taste for rum and brandy.

Traders figured out that by offering Native Americans alcohol they could keep them around and willing to continue trading. Yet, it also harmed Native American communities and led to accidents, violence and even murder, Mancall said.

“Alcohol had a complex role in the fur trade,” Mancall said. “Colonial officials recognized it caused destruction and destabilized communities, but traders … found alcohol was a great commodity that could be manipulated by watering it down and selling it to native people, thus functioning as a currency.”

Alcohol to Europeans who wanted to control the Americas was a perfect product, Mancall said. The European colonists wanted Native Americans to adopt Christianity and participate in a market economy. Native Americans, seeing the damage alcohol wrought, protested vigorously. However, Europeans argued that if Native Americans didn’t trade, they would become lazy and that would be a backwards step on their road to “civilization.”

At the end of the day, it’s an inescapable fact that alcohol was an agent of empire building in North America, Mancall concluded.

“No one can claim the Europeans were unaware of what was happening,” he said, “but the forces of colonialism overpowered the indigenous voices of protest.”