A diet that mimics fasting may reverse Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes

A diet designed to imitate the effects of fasting appears to reverse diabetes, a new USC-led study shows.

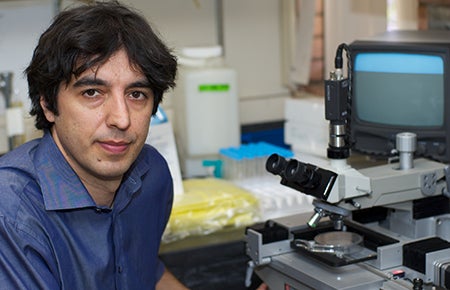

The fasting-like diet promotes the growth of new insulin-producing pancreatic cells that reduce symptoms of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in mice, according to the study on mice and human cells led by Valter Longo, professor of gerontology and of biological sciences at USC Dornsife.

“Cycling a fasting-mimicking diet and a normal diet essentially reprogrammed non-insulin-producing cells into insulin-producing cells,” said Longo, who directs the Longevity Institute at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

By activating the regeneration of pancreatic cells, the researchers were able to rescue mice from late-stage Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. They also reactivated insulin production in human pancreatic cells from Type 1 diabetes patients.

The reprogrammed adult cells and organs prompted a regeneration in which damaged cells were replaced with new functional ones, Longo said.

The study published on Feb. 23 in the journal Cell is the latest in a series of studies to demonstrate promising health benefits of a brief, periodic diet that mimics the effects of a water-only fast.

Reversing insulin resistance and depletion

In Type 1 and late-stage Type 2 diabetes, the pancreas loses insulin-producing beta cells, increasing instability in blood sugar levels. The researchers simulated Type 1 diabetes in mice by administering high doses of the drug streptozotocin — killing the insulin-producing b-cells — and studied mice with Type 2 diabetes, characterized by insulin resistance and eventual loss of insulin production, which have a mutation in the gene Lepr.

The study showed a remarkable reversal of both types of diabetes in mice placed on the fasting-mimicking diet for four days each week. They regained healthy insulin production, reduced insulin resistance and demonstrated more stable levels of blood glucose. This was the case even for mice in the later stages of the disease.

The diet cycles switched on genes in the adult mice that are normally active only in the developing pancreases of fetal mice. The genes set off production of a protein, neurogenin-3 (Ngn3), thus generating new, healthy insulin-producing beta cells.

Next steps: clinical study

Longo and his team also examined pancreatic cell cultures from human donors and found that, in cells from Type 1 diabetes patients, fasting also increased expression of the Ngn3 protein and accelerated insulin production. The results suggest that a fasting-mimicking diet could alleviate diabetes in humans.

Valter Longo, professor of gerontology and of biological sciences at USC Dornsife. Photo by Dietmar Quistorf.

Longo and his research team have gathered evidence indicating several health benefits of the fasting-mimicking diet. Their recent study published in Science Translational Medicine demonstrated that the fasting-mimicking diet reduced risks for cancer, diabetes, heart disease and other age-related diseases in human study participants who followed the special diet for five days each month in a three-month span.

Prior studies on the diet have shown potential for alleviating symptoms of the neurodegenerative disease multiple sclerosis, increasing the efficacy of chemotherapy for cancer treatments and decreasing visceral fat.

These findings warrant a larger FDA trial on the use of the fasting-mimicking diet to treat human diabetes patients to help them produce normal levels of insulin while improving insulin function, Longo noted.

“Hopefully, people with diabetes could one day be treated with an FDA-approved fasting-mimicking diet for a few days each month and gain control over their insulin production and blood sugar,” he said.

About the study

Among the study’s lead authors were Chia-Wei Cheng and Roberta Buono of USC Davis and Valentina Villani of the Saban Research Institute. Other co-authors were Min Wei and Dean Pinchas Cohen of USC Davis; Sanjeeve Kumar of the Keck School of Medicine of USC; Omer Yilmaz of the Koch Institute at MIT, Julie Sneddon of the University of California, San Francisco, and Laura Perin of the Saban Research Institute. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (grants AG20642, AG025135 and P01 AG034906) to Longo.

Longo is the founder of and has an ownership interest in L-Nutra; the company’s food products are used in the human studies of the fasting-mimicking diet. Longo’s interest in L-Nutra was disclosed and managed per USC’s conflicts of interest policies. USC has an ownership interest in L-Nutra and the potential to receive royalty payments from L-Nutra. USC’s financial interest in the company has been disclosed and managed under USC’s institutional conflict of interest policies.