Sci-fi Fandom and Gay Rights

If you wanted to find life outside the closet in the 1930s, you might as well have started looking for another planet — and that’s exactly what a generation of gay and lesbian sci-fi fans did.

They were drawn to a genre that allowed them to imagine new worlds where they could be their true selves and love whomever they wanted.

This Fall, a senior seminar offered through USC Dornsife’s Gender Studies Program will look at how Los Angeles’ legendary sci-fi societies overlapped with the early LGBT rights movement, laying the groundwork for activists long before Stonewall or the Black Cat Riots.

Challenging students

Gender Studies 410 will ask students to conduct original research using materials from ONE National Gay and Lesbian Library and Archives USC Libraries, the largest LGBT archive in the world. Joseph Hawkins, associate university librarian and director of ONE Archives, who is teaching the class, said the course will let students work with rare primary documents while challenging them to find new ways of thinking about gender and sexuality.

“I want my students to develop an appreciation for research,” Hawkins said. “I get so depressed when students pull everything off Wikipedia. I want them to look at original documents and get as jazzed about them as I do.”

Part of the archive began as the personal collection of letters, photos and other documents belonging to Jim Kepner, an early gay rights activist. In 1953, Kepner and his colleagues began publishing ONE Magazine, the country’s first widely distributed gay journal. It was eventually the subject of a landmark Supreme Court case on the First Amendment.

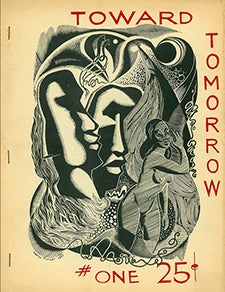

But decades before ONE, Kepner worked on sci-fi zines like Toward Tomorrow and The Western Star. These publications were first and foremost about space travel and imaginary futures. But they allowed Kepner and others to learn how to run a mimeograph machine, write articles and connect with groups across the country.

Toward Tomorrow, a science fiction magazine created by Jim Kepner, 1944. Courtesy of photo/ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

“I think a really great case can be made for the fact that they learned how to do their gay publishing from their involvement in science fiction,” Hawkins said. “There’s this tension between flights of fancy and, on this other side, really serious work about homophobia and sexism and racism. There was this conceptualization of what the world might be if it was better.”

Reading between the lines

The stories and commentary in these journals served as incubators for ideas that would lead to political organizing decades later. Sci-fi allowed readers to safely engage with thoughts about alien races with mixed genders or finding love despite their differences. In the 1930s, these messages were actually more overt; by the McCarthy era, the culture’s atmosphere had stifled messages about gay or lesbian themes.

“You have to read between the lines,” Hawkins said. Publications like Weird Tales or other “creature magazines” often featured monsters carrying off nude women — and were being illustrated by female artists. The same was true for some illustrations featuring men. Considering the artists’ sexual backgrounds lends a different context to who these clichéd monsters represented — one that says more about life on Earth than anywhere else.

In the days before the Internet, sci-fi magazines also served as an early precursor to discussion forums. Readers traded letters about space exploration as well as changes in society. They even trolled one another, igniting epic arguments about politics and other subjects.

The readers in these circles include a who’s who of classic sci-fi: Ray Bradbury, Robert Heinlein and the omnipresent L. Ron Hubbard were all highly active. So was superfan Forrest Ackerman, publisher of Famous Monsters of Filmland.

But just like Internet forums, most people wrote using nom de plumes, allowing them to express a side of themselves that was often kept hidden. Kepner himself had about 14 different pseudonyms ranging from esoteric references to unprintable humor.

Some gay and lesbian writers had entire alter egos to go with their names. One of those writers was “Lisa Ben” — an anagram of “lesbian” — who worked as a Warner Bros. secretary and used company equipment to print the first lesbian zine in the United States. But she also was known as Tigrina the Devil Doll, a kind of proto-Catwoman with her own handmade costume.

All those pseudonyms make for intensive detective work. Hawkins and others at ONE Archives have had to sleuth out who is who and what the relationships were between everyone. Those skills are vital to archival research, he said, and have helped to uncover unexpected connections between sci-fi and LGBT communities across the country, and even internationally.

“It’s networking,” Hawkins said. “It’s way before the Internet, but it’s everything the Internet is going to anticipate.”