Living the California Dream

When the USC Dornsife undergraduates picked their way across the stepping stones spanning the koi-filled pool and walked through the glass doors of John Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein Residence, there was a collective intake of breath.

Perched atop a steep hillside above Benedict Canyon and commanding panoramic views of the city skyline, Lautner’s dramatic angular concrete masterpiece had literally taken their breath away.

“Our jaws dropped when we walked into this house and I don’t think we ever really closed them,” said Rebecca Michelson, an art history major. “Nothing has equaled the sense of awe we felt as we experienced this unbelievable home.”

Megan Luke (standing) and students visit Richard Neutra’s radical VDL Research House II overlooking Silver Lake Reservoir in Los Angeles. Photo by Matt Meindl.

Michelson, a senior, and five other USC Dornsife students were touring the Lautner house as part of the Maymester course “Living the California Dream: Modern Domestic Architecture and Design in Los Angeles.” Led by Megan Luke, assistant professor of art history, the four-week course introduced undergraduates to the history of modern architecture by enabling them to experience firsthand many of the city’s most iconic 20th-century homes.

Los Angeles: A rich laboratory

“The built environment of Los Angeles is a rich laboratory for understanding social concerns that have shaped the city’s history over the last century,” Luke said. “By enabling them to physically experience the work of major architects like Charles and Henry Greene, Frank Lloyd Wright, Rudolph Schindler, Richard Neutra, John Lautner and A. Quincy Jones, students are gaining the critical skills and historical knowledge necessary to answer questions about how a private home can exemplify particular arguments about the collective life of a city.”

Organized chronologically, the course began with a visit to the Gamble House in Pasadena, an outstanding example of an Arts and Crafts style bungalow — the starting point for a Southern California domestic architectural vernacular. Designed by Greene and Greene in 1908, the house is operated by USC School of Architecture.

This Tree of Life design on the leaded art-glass entry at Greene and Greene’s 1908 Gamble House in Pasadena pays homage to the principal material used in the construction of the house. Photo by Tim Street-Porter, courtesy of the Gamble House.

“We got to think about this particular architectural firm and its importance in developing the Los Angeles Craftsman bungalow aesthetic,” Luke said. “We also visited other Pasadena neighborhoods, like the Arroyo Terrance neighborhood and Bungalow Heaven, and considered what became of this magisterial, monumental housing for elite wealthy resort vacationers in Pasadena. We saw how that trickled into a housing style for much more modest homes built by anonymous contractors who nevertheless used some of the visual qualities that Greene and Greene pioneered.”

Students then concentrated on Frank Lloyd Wright and his far-reaching influence on modernist architecture through his designs for the Hollyhock House and his textile block homes.

Next, students explored the architecture of Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra, two practitioners who were deeply indebted to Wright and who moved to Los Angeles from Vienna, Austria, because of their encounters with him.

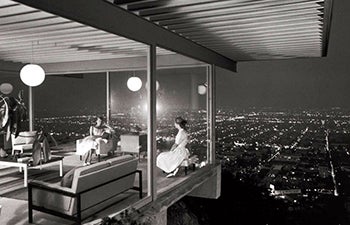

The last week of the course was devoted to post-war modern architecture, with visits to three Case Study Houses — the steel and glass Eames House, and the Stahl House and Bailey House, both designed by Pierre Koenig, a graduate of USC School of Architecture. The Case Study Houses were experiments in American residential architecture. Sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine, which commissioned major architects of the day to design and build inexpensive and efficient model homes for the United States residential housing boom, the program ran intermittently from 1945 until 1966. Thirty-six Case Study Houses were designed, of which 24 were built.

Indoor-outdoor living

The course required students to think about questions of urbanism, preservation and the mediation of architecture, especially through photographs. To further their understanding, students visited the archives of Greene and Greene, Neutra and legendary architectural photographer Julius Shulman.

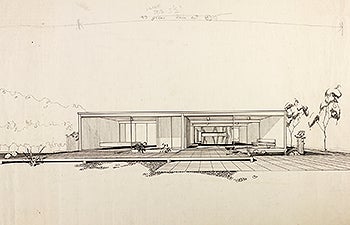

A rendering of the 1959 Bailey House in the Hollywood Hills by architect Pierre Koenig who designed it for the Case Study House Program.

They also considered the defining principles of Los Angeles modernist architecture, foremost among them its commitment to indoor-outdoor living. An outstanding example is Neutra’s 1966 VDL Research House II in Silver Lake. Air, light and water combine in a series of patios, courtyards, pools, mirrors and roof terraces in a house where every single room — even the bathroom — is equipped with a door that opens to the outside.

“It was so airy and light,” said Linda Wang, who graduated in May with a double major in philosophy, politics and law, and sociology. “Coming from the darker spaces of Wright’s Hollyhock House I could see how revolutionary Neutra’s house was and what a statement it made.”

Architecture as a manifesto of the radical and the Bohemian

The concept of architecture as manifesto was one the students rapidly became familiar with.

“Los Angeles is traditionally a place where you come to either vacation or reinvent yourself,” Luke said. “So we’ve been thinking a lot about this place as a very receptive environment for radical modernist architectural ideas to support and foster progressive political bohemian lifestyles — whether it be Aline Barnsdall and the arts complex she hired Wright to create at the Hollyhock House, or the Eames trying to reinvent how we interact with objects through their artistic practice.

“All the houses we are visiting were making radical, highly unusual statements that required a certain visionary quality on the part of the architect and the client. These are buildings that are not just meant for private use, but are declarative statements.”

A new visual acuity

Through the course, Luke aimed to enhance students’ visual acuity for architecture. “I want them to go beyond questions of taste and think more critically about what specifically in the built environment is causing us to have an emotional response and what these buildings want to tell us.”

Widely considered one of the most iconic images of Los Angeles mid-century architecture, this nighttime photograph of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House 22, also known as the Stahl House, is by renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman.

Wang said that before taking the course she took the built environment for granted.

“Now I have more of an understanding of how architecture influences — and is influenced by — social forces in history,” she said. “I also understand that there is no such thing as a building that exists alone in a void. Every building reflects influences of architects that came before it and will itself continue to influence those who come after it.

“This course has forced me to give up my preconception of what a house is and look at all the different ways a home could be.”

Michelson agreed.

“Now when I enter a building I think, ‘Someone designed this for me to walk into and experience.’ I definitely wasn’t thinking about that before this class.”