Japan, Spies and the Roman Empire

Research into a Hollywood-based Jewish spy ring is one of three USC Dornsife faculty research projects that have been honored with a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant for the academic year 2015-16.

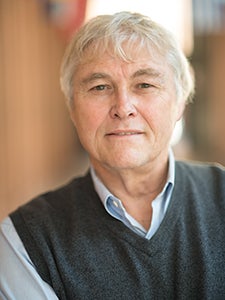

Steven Ross, professor of history at USC Dornsife, will use the grant to advance research on his book, Hitler In Los Angeles: How Jews and their Spies Foiled Nazi and Fascist Plots against Hollywood and America, describing how the spy ring infiltrated and sabotaged Nazi and fascist groups in the United States in the 1930s and 40s.

Ross is joined as an NEH awardee by Jacques Hymans, associate professor of international relations and John Pollini, professor of art history and history.

Created in 1965 as an independent federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities supports research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities by funding selected, peer-reviewed proposals from around the nation.

Winning an NEH grant will allow Steven Ross to finish his book on a Jewish spy ring that infiltrated and sabotaged Nazi groups in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood. Photo courtesy of Steven Ross.

Ross said he was both surprised and delighted to receive an NEH Fellowship.

“This NEH grant allows me to devote 2015 to finishing my manuscript and sending it off to Bloomsbury Press,” said Ross, co-director of the Casden Institute For the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life, based in USC Dornsife. “There are some unknown histories that demand to be told. This is one of them.”

In his book, Ross reveals how 1930s and ’40s Hollywood studio bosses, long denigrated for their capitulation to Hitler through their censorship of movies critical of the Nazi regime, were privately funding a Jewish spy operation.

Ross’ book will come on the heels of Ben Urwand’s controversial 2013 book, The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler, which accused Jewish Hollywood studio heads of actively collaborating — rather than simply cooperating — with the Hitler regime.

“My book presents a very different story: one of Jewish resistance to Hitler,” Ross said. “The same moguls Urwand accused of kowtowing to Hitler funded a spy ring run by attorney Leon Lewis, the man Nazis called the “most dangerous Jew in Los Angeles,” from August 1933 to the end of World War II.”

Nazi leaders saw Los Angeles as the perfect place to establish a beachhead for their hoped-for assault on the Pacific Coast. Not only did Southern California have a long history of anti-Semitism and rightwing extremism, but the L.A. port was less closely monitored than “Jew York,” as Nazis called it. This made L.A. easier to use as a central depot for sending spies, money, propaganda and secret orders from Germany — all of which were then distributed throughout the United States.

“To achieve their goal of American conquest, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels adopted a two-prong strategy,” Ross said. “Keep America neutral by controlling Hollywood and establish a ‘Fifth Column’ along the West Coast.”

Comprised of military veterans and their wives who infiltrated every Nazi and fascist group in Los Angeles, Lewis’ spy ring uncovered a series of Nazi plots to kill the city’s Jews and sabotage the nation’s military installations.

“Plans existed for hanging 20 prominent Hollywood figures such as Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, and Jack Warner; for driving through Boyle Heights and machine-gunning as many Jews as possible; and for blowing up defense installations and seizing munitions from National Guard armories on the hoped-for day that Nazis would launch their American putsch,” Ross said. “Since U.S. law enforcement agencies were not paying close attention —preferring to monitor Reds rather than Nazis — there was only one thing that stood in their way: Jewish ingenuity.”

However, despite the quality and quantity of Lewis’ intelligence gathering efforts, U.S. authorities repeatedly ignored his reports. Only after Pearl Harbor did government officials come to Lewis for help, Ross said. Lewis supplied Naval and Army Intelligence, the Secret Service, the Justice Department, the FBI, the U.S. Office of War Information, the Attorney General’s office, and the California Attorney General’s office with a list of thousands of Nazis and fascists, aliens and Americans, working secretly or openly since 1933.

However, there was a price to pay for such vigilance, Ross noted.

“Two of Lewis’ spies who testified against Nazis in open court or at HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) hearings died suspicious deaths: one of a smashed-in skull, the other seemingly poisoned, while other undercover agents received beatings and death threats.

“The NEH grant will allow me to present this important and previously neglected story to a large audience sooner rather than later.”

John Pollini, professor of art history and history, was awarded the grant for his book, Destruction, Mutilation, and Repurposing of Classical Images in Late Antiquity, which examines the enormous body of archaeological evidence for Christian destruction, mutilation and desecration of the images of the polytheistic peoples of the former Roman Empire.

John Pollini’s NEH grant enables him to concentrate on his book examining archaeological evidence of Christian destruction, mutilation and desecration of images of the polytheistic peoples of the former Roman Empire. Photo by Peter Zhaoyu Zhou.

Chosen by the Archaeological Institute of America to give the Martha Sharp Joukowsky Lectures on this subject at 14 universities throughout the U.S. Canada and Italy in 2012 and 2013, Pollini has also published three articles and given several papers at professional conferences on various aspects of this research.

“It was rather surprising to learn how few of my colleagues in the field of classical art, archaeology and ancient history were aware of this phenomenon, or the extent of the damage caused at the time as a result of religious intolerance and the lack of respect for others’ belief systems — something we are only too familiar with today due to contemporary examples of religious extremism.”

Pollini said he was delighted to receive the award.

“This NEH grant will afford me the time to concentrate on completing a substantial amount of my book project, since it’s difficult to work uninterruptedly on such projects while teaching and fulfilling other academic commitments,” he said. “I’m also grateful to the administration of USC, which encourages faculty to apply for fellowships even outside the sabbatical cycle.”

Pollini believes his study will be of particular interest to scholars and students of archaeology, art history, history, religion, and classical literature, as well as political and social sciences.

“I am also convinced that it will have an impact outside the fields of classical and late antique studies, in that it will appeal to those intellectually curious about the interrelation of art, politics and religion, as well as those concerned with the power of images, the destruction of cultural property, and the psychology of violence,” he said.

Pollini is particularly interested in bringing a new dimension to our understanding of how human beings conceive of images as substitutes for what is represented, as objects for adoration or defilement, depending on time and circumstances in a changing religious, political and societal milieu.

“Evidence of intentional damage and desecration in the distant past — as in the case of the Parthenon sculptures — is also relevant in discussions about the ownership of the material culture of ancient peoples,” he said. “These ancient peoples were quite different both culturally and religiously from those who now occupy the lands in which some of the greatest works of art and architecture of Western Civilization were created.”

Hymans received the NEH Fellowship for Advanced Social Science Research on Japan, a joint activity of the Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission and the NEH, for his project “The International Politics of Sovereign Recognition: The West and Meiji-era Japan.”

Awards support research on modern Japanese society and political economy, Japan’s international relations and U.S.- Japan relations. Hymans’ research aims to contribute both to an historical understanding of the recognition of Japan’s sovereignty by Western states at the end of the 19th century and to a broader theoretical understanding of the dynamics of recognition in the modern state system.

The NEH grant will allow Jacques Hymans to complete his research into the fundamental reasons why the West finally granted Japan sovereign recognition prior to World War I. Photo by Peter Zhaoyu Zhou.

Stating that it was a tremendous honor to win an NEH grant, Hymans added that he felt particularly privileged to receive it because he had not originally trained as a Japan specialist.

“I take the fellowship award as a validation of the hard work that I have done over the past few years to build an ambitious new research agenda on Japan’s place in the world, even as I have continued to develop my original research agenda on international nuclear politics,” he said.

As the only Far Eastern and, arguably, the only nonwhite state to become a full member of the international “comity of nations” prior to World War I, Japan’s success in achieving international recognition of its sovereignty was a major diplomatic accomplishment and the harbinger of a new era in international history.

“A number of recent studies have focused on Japan’s long quest for international recognition, but we have much less understanding of the decision-making processes inside the Western states that granted it,” Hymans said. “What forces were pushing them to recognize Japan, and why did they prevail at the end of the 19th century?”

Hymans’ research to date shows that the Western recognition of Japan reflected the decline of traditional aristocratic conceptions of international society and the concomitant rise of rationalized bureaucratic state organizations that sought consistency and predictability in their international relationships.

“This, coupled with Japan’s extremely successful efforts to develop a bureaucracy that was able to provide the Western states with the consistency and predictability they craved, may well provide the fundamental answers to why the West finally granted Japan sovereign recognition,” Hymans said.

“Thanks to the NEH award, next academic year I will be able to devote all my time to reading deeply on this topic and conducting historical archival research in Europe, the U.S., and Japan in close collaboration with Japanese scholars.”