Under the Skin

It’s difficult to forget the harrowing images of emaciated, hollow-eyed Romanian orphans whose plight was revealed after the fall of Communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu’s brutal regime in 1989.

“When children are traumatized, rather than the heightened pattern of stress response that one might expect, many actually show a dampened or blunted response,” said Darby Saxbe, assistant professor of psychology at USC Dornsife.

“This can vary from child to child. Studies of the Romanian orphans showed hyperactive profiles of responding but also very flattened patterns. A blunted profile may be an adaptive response to a very high stress environment because it protects the body from being overloaded by a stress response that is constantly being deployed.”

Saxbe’s work focuses on understanding how family and other close relationships affect health and well-being. Studying cortisol patterns, she found similarly blunted patterns of response among American adolescents living in aggressive family environments.

“I’m really interested in looking under the skin to understand how our relationships and our social experiences affect our individual physical bodies,” said Saxbe, who was recently named a Rising Star by the Association of Psychological Science for her research into how fluctuations in levels of the stress hormone cortisol are dependent on family environments.

“I wanted to find out what happens to these kids’ stress response systems when their parents fight aggressively. I found the kids show a dampened cortisol pattern, indicative of a lowered stress response, when they are in a family conflict situation.”

Saxbe believes this may be an adaptive pattern to protect them from risks of post-traumatic stress symptoms and anti-social behavior.

Next, she used neuroimaging to study a possible link between adolescents’ family environments and how their brains respond to social stimuli.

Saxbe worked with a sample of adolescents originally recruited to participate in the USC Family Studies Project, which her postdoctoral mentor Gayla Margolin, professor of psychology and pediatrics, directs. Her co-mentor on her postdoctoral fellowship grant was Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, assistant professor of psychology at USC Dornsife’s Brain and Creativity Institute and assistant professor of education at USC Rossier School of Education.

In an earlier wave of the study, they asked parents and teenagers to identify hot topics within their family that reliably get everyone upset.

“It’s usually things like teenagers texting too much or parents who don’t like the teenagers’ friends,” Saxbe said. “They were given 15 minutes to discuss that topic and were told to make sure everyone gets their point across.”

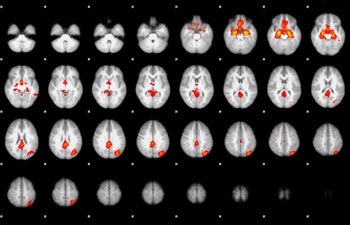

These heated exchanges were videotaped. Five-second silent clips of these videos were then shown to the teenagers while they underwent a neuroimaging scan at the USC Brain and Creativity Institute, housed at USC Dornsife. The clips showed their own faces, those of their parents, or of adolescent peers who had been videotaped separately in arguments with their own parents.

Asked to describe how they thought the person shown was feeling, the youths’ brain scans showed them responding differently to the faces of their peers than their parents’ faces.

“We find that when they look at their parents, they activate self-relevant areas of the brain linked to processing information about the self. When they see the peer, the areas of the brain that are activated appear to be those linked to social reward.”

Neuroimaging appears to bear out the theory that more energy and effort are put into peer relationships in adolescence than into relationships with parents. Next, Saxbe plans to look at how these patterns might vary among the adolescents coming from more aggressive families.

A screenshot from a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study conducted by Darby Saxbe shows the brains of adolescents reacting to video clips of their peers. Saxbe’s research suggests that youths use different parts of the brain to process peer rather than parent emotions. Image courtesy of Darby Saxbe.

Her research can help us understand why adolescents from aggressive households may behave aggressively themselves or be victimized by aggressors in the future as a result of a lack of social skills and how they read information in others.

“I think a lot of psychology is biased by an exclusive focus on the individual,” Saxbe said. “I’m really interested in interconnectedness and looking at the fact that we are all embedded within a social web.”

Saxbe is also interested in how the way couples negotiate responsibilities affects health across the lifespan. She has found a link between marital satisfaction and women’s cortisol levels.

Ideally cortisol — which is implicated in metabolism, circadian rhythms, immunity and cardiac functioning — peaks early in the morning and diminishes over the course of the day. Women who reported happy marriages tend to follow this cortisol pattern, Saxbe found. Those who reported marital dissatisfaction experienced more even cortisol levels throughout the day.

Saxbe also studied how cortisol levels in couples are affected by the distribution of housework.

She found those who spend more time doing chores don’t experience an adaptive drop in cortisol at the end of the day. As women do more housework than men, her findings on cortisol levels may have particular implications for women’s health.

“A dysregulation in the body’s stress response system can lead to long-term negative outcomes like disease and mortality risks. It’s hard to know if these changes in cortisol patterns will contribute to a difference in life span, but research suggests that little alterations can have long-term effects.”

Saxbe, who earned a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from UCLA, was inspired to come to USC as a postdoctoral researcher after meeting Margolin at a research meeting. “Gayla’s so great, so dynamic and I’d heard all these wonderful things about her.”

With Margolin’s help, Saxbe successfully applied for a postdoctoral grant, administered through the National Institutes of Health.

“The grant gave me three years of funding to come to USC and get involved in all Gayla’s projects. I learned so much working with her,” Saxbe said.

In her second year, a tenure track position opened up in clinical psychology and she jumped at the opportunity.

“I am really thrilled to be here,” she said. “I am a very proud Trojan.”