In Memoriam: Anthony Mlikotin, 87

Professor Emeritus of Slavic Languages and Literatures Anthony Mlikotin, founding chairman of the department and 31-year faculty member at USC Dornsife, has died. He was 87.

Mlikotin died on Sept. 13 at Seacrest Convalescent Home in San Pedro, Calif. from pneumonia.

Joining USC Dornsife in 1965, he became founding chairman of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures two years later. In three years, the number of students taking classes in the department rose from 33 to 266. Currently, about 500 students attend Slavic classes.

Mlikotin retired in 1996 at age 72 as professor emeritus, but continued to stay connected to faculty and students, driving to campus two or three times weekly to visit the Slavic department, talk with professors, go to the library or cafeteria to drink coffee and chat with friends.

“He told me, ‘I just like to be around students,’ ” said Mlikotin’s daughter, Dunja Wright ’90. “USC was his home. He really loved what he did and he kept returning.”

Thomas Seifrid, professor and chair of Slavic languages and literatures, said the department would not be what it is today without Mlikotin.

“Anthony Mlikotin was a lively presence in the department — which has now risen to become one of the top Slavic departments in the country — for all who knew him when he was still teaching at USC,” Seifrid said.

“He taught energetically and took his students’ potential for intellectual engagement — especially with his favorite philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche — seriously, expecting them not only to read and comprehend the text but think deeply about what it might mean for their lives. In this regard, he always struck me as a European scholar of an earlier era, one whose own intellectual journey was relevant to his teaching in a particularly immediate way.”

Sarah Pratt, professor of Slavic languages and literatures and vice provost for graduate programs, was greatly impressed by Mlikotin’s urgent engagement with intellectual pursuits.

“As a department member, you’d go into Anthony’s office wanting to talk about G.E. class enrollments and realize when you came out an hour later, that you’d solved the enrollment issues in 5 minutes and then spent 55 minutes discussing the philosophical bases of Georg Christoph Lichtenberg’s aphorisms. In his unstoppable commitment to ideas, to critical thinking, Anthony embodied the very purpose of the university.”

Mlikotin’s wife Barbel Mlikotin sat in on one of her husband’s classes, Wright recalled. Barbel marveled at her husband’s ability to make 19th century philosophers such as Nietzsche relevant to daily life.

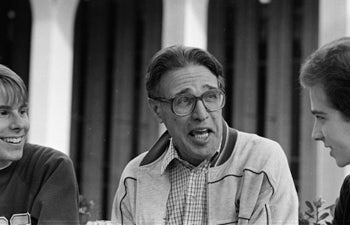

USC Dornsife’s Anthony Mlikotin chats with some of his students on USC’s University Park campus in 1988. Photo by Irene Fertik.

“When I was attending USC, his office and his classes were always full,” Wright said. “Students were so interested, and I thought it was pretty wonderful that the professors and he, as the leader of the department, could get 18-year-olds interested in the field.”

Mlikotin, known to friends as “Ante,” was born in 1925 in Zagreb, located in present-day Croatia. After earning a bachelor’s degree in humanities in Croatia, he immigrated to the United States in 1952, traveling across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City by freighter. He was among the first international students to be accepted by Indiana University, where he earned his master’s degree in Slavic languages and literatures in 1958 and his Ph.D. in comparative literature in 1960.

Proficient in many languages, he spoke Serbo-Croatian, Russian, German, French, Spanish, Italian and Latin. Before joining USC Dornsife, he taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, San Francisco State University and the University of Colorado.

He published several books on philosophy and Russian literature, including Genre of the International Novel in the Works of Henry James and Turgenev (University of Southern California Press, 1971), Western Philosophical Systems in Russian Literature (University of Southern California Press, 1971) and As Literature Speaks (University of Southern California Series in Slavic Humanities, 1983). He wrote more than 25 articles and a number of reviews, translations and teaching manuals.

Family and friends will remember Mlikotin for his charm, wit and giving heart.

“He was a very happy man,” Wright recalled. “He always had good humor and loved to travel. Since my parents were European, they took us back every summer to see family. He knew a lot about the world, and in Europe, we could ask him about any war, any cathedral, he knew the history of everything. He was like a modern-day Google.

“He had a very serious, deep side to him, but he was also very fun-loving.”

Seifrid said the Slavic department is “enormously grateful” for Mlikotin’s foundational work to bring the study of Russia and other Slavic cultures to USC.

“We will miss Anthony deeply,” he said.

He is survived Barbel Mlikotin, his wife of 49 years, Wright, his son Marko Mlikotin, and five grandchildren.