The Goddess of the Dawn

In the poem, “The Aurora of the New Mind,” the narrator fluffs up the pillows then won’t let the reader get comfortable.

There had been rain throughout the province

Cypress & umbrella pines in a palsy of swirling mists

Bent against the onshore whipping winds

I had been so looking forward to your silence

What a pity it never arrived.

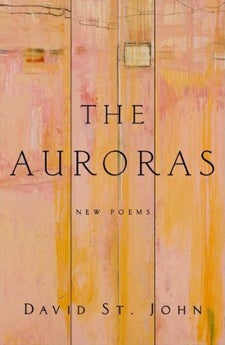

“I wanted something double-edged and biting,” said David St. John, professor of English in USC Dornsife, referring to the poem in his new book The Auroras (HarperCollins, 2012). “I wanted to create tonal shifts and shift the ground slightly before the poem went on.”

Still I look a lot like Scott Fitzgerald tonight with my tall

Tumbler of meander & bourbon & mint just clacking my ice

To the noise of the streetcar ratcheting up some surprise

I had been so looking forward to your silence

& what a pity it never arrived.

“With the repetition, that last line, that refrain is slightly different,” St. John said. “The first time it’s meaner and more aggressive. The second time it’s sadder; the reader experiences the line with a greater poignancy.”

Separated in three sections like a triptych, the book’s first part is comprised of poetry with songlike motifs and surreal imagery. The second section contains shortly lined poems with taut language recalling the landscapes of St. John’s youth. These are actual physical landscapes but also emotional landscapes. For example in “The Empty Frame,” when St. John describes a “shaky one-room cottage” and the “white limbs of an ancient oak,” he could have been referring to how he felt about himself at the time.

Sinking into the long white grass

I could also see I swear to you just

Above & slightly to the right of the three

Concrete steps leading up to what

Now was nothing & no doorway I could see hanging there impossibly

In the air exactly as it had always hung

Yet now only as the empty frame

Of the landscape nailed upon

The crossbeam of the blackening night

“In general, as in ‘The Empty Frame,’ I wanted there to be for the reader this solidity of an actual physical place and from that sense of security I could allow a metaphor of disquiet to arrive,” St. John said. “After providing something solid in the landscape I could create some tremors through that land.”

What often surfaces is something that’s quite troubling.

“Something that sends a kind of ripple and apprehension across that landscape,” he said. “The landscape that is, in fact, the emotional landscape that is layered on top of the physical landscape.”

The final section of the book switches to longer, meditative, philosophical and even discursive lines.

“I didn’t know if people would feel like these are three distinctly different parts,” St. John said. “But I’m relieved to know readers are experiencing the book as a whole.”

Reading the collection of poems can feel like peering into a kaleidoscope. As the viewer looks into one end of the cylinder and sees mirrors embedded with colorful bits of glass or pebbles, light enters the other end, creating a vivid pattern. As the cylinder is turned, the pattern changes form and color.

St. John’s poetry, too, keeps shifting perspective so as readers move through the poems, they can step into the landscape of the language and experience the events the same way they experience events in their own lives.

“A poem is not meant to be like a leaf pressed between the pages of an anthology,” St. John said. “A poem has to be thought of as an active and vital human voice. The mind itself is always in motion and never static. The consciousness in the poem that the reader is experiencing needs to be in motion as well.”

Light and dark hold equal value in the book. Aurora is the Latin word for dawn. In Roman mythology, Aurora is the goddess of the dawn. An aurora is also a natural light display in the night sky that can look like glowing, dancing ribbons of electric greens, reds and blues. They are caused by the interaction of solar winds with the Earth’s magnetic field.

The title, The Auroras, recognizes the work of Wallace Stevens who wrote The Auroras of Autumn in 1950.

The Auroras, David St. John’s latest poetry collection, explores the beauty of change.

“Wallace Stevens has been one of the main influences on my poems from the beginning and I really wanted to acknowledge that,” St. John said. “Also, I liked the idea of The Auroras suggesting not only the ephemerality, but also the kaleidoscope — always in constant change.”

In “Dark Aurora,” the last poem of the third section, St. John finds a kind of quiet peace in the dark.

If death has a form, it is the form of departure. If death has a form,

it is lit by darkness. Everything we’ve looked for all these years,

everything together we’ve called some necessity of invention, any

syllable & symbol, every penetrating & luminous or prodigious desire,

every carved line on every page has emptied into this flesh, this flash

of revelation, this form which is no memory, which is our dark, the form

of dark, & darkness in its final form.

When asked why the book seems to end on a bleak note, St. John suggests a better question would be, “Why begin with the dawn and end with the dark?”

Just as light contains dark, the dark contains light, St. John said.

“And they are both deserving of that embrace, which is finally the one human thing we have a choice about,” St. John said. “I’m at least offering [readers] the possibility that there’s a kind of beauty in thinking about change. And the change that can incorporate both the light and dark I find really compelling. I have no desire to disappear into the dark but I have every desire to recognize the peace and the beauty of what a lived life can bring us toward.”

But no one really knows what happens at the end of life.

“That is the premise,” St. John replied. “Maybe the dark we imagine is in fact light.”