Faith, Beauty and Music: Q&A with Composer Mark Nowakowski

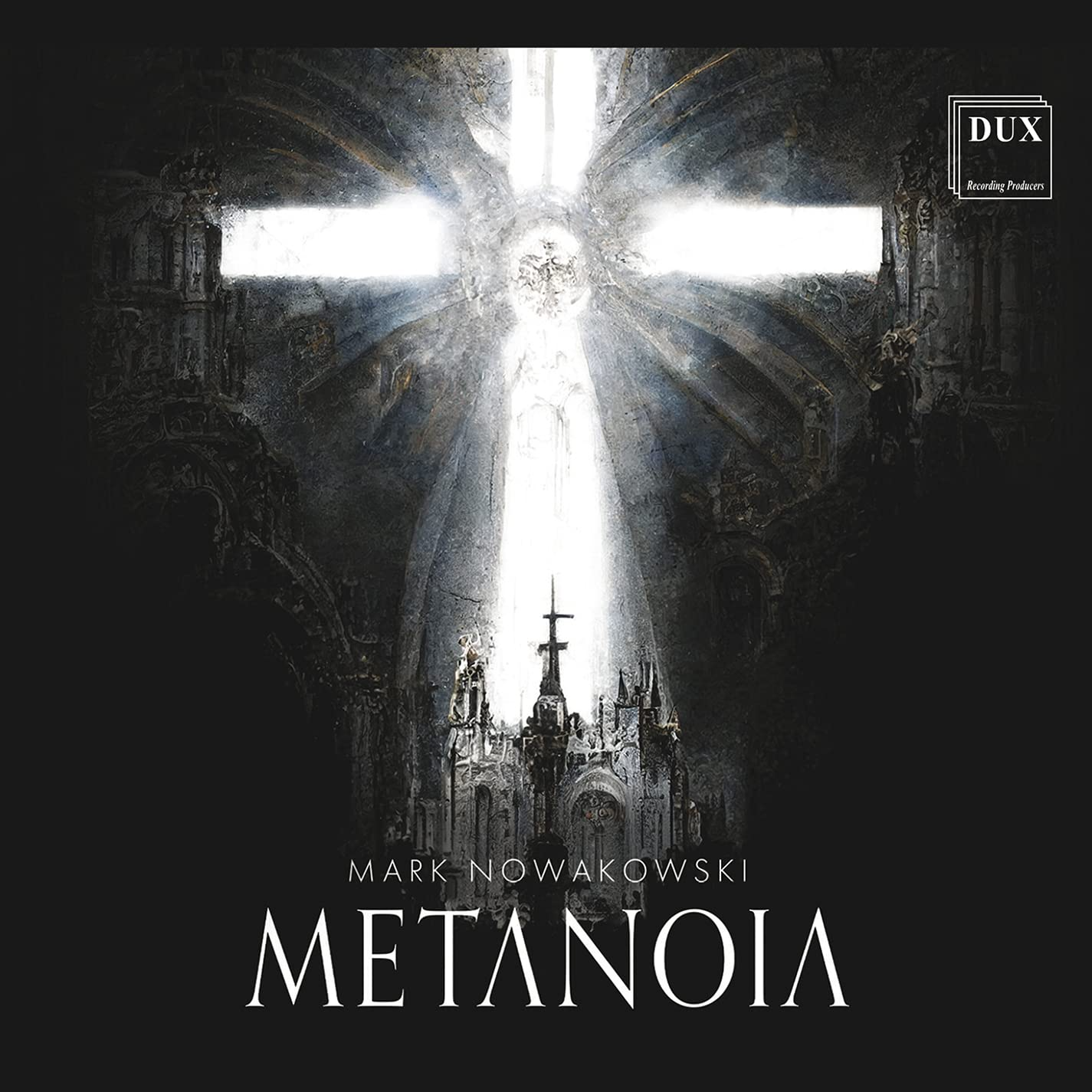

Chicago native Mark Nowakowski is an author, musician and composer whose work is performed globally and deeply influenced by Catholic mysticism. His album “Metanoia” is now available from Dux Records on Spotify and Apple Music, and at current.marknowakowski.com.

An associate professor of music at Kent State University at Stark in Ohio, he earned a master’s degree from the University of Colorado, and undergraduate degrees in music theory and arts technology from Illinois State University.

In the Q&A below, Nowakowski discusses his life, how faith informs his work and the role of beauty in the creative process.

IACS: Tell us a bit about growing up — how does your experience as the son of Polish immigrants in Chicago influence your work?

Nowakowski: My family was not officially musical, but there is definitely a latent musical gene rattling about on my mother’s side. My mother herself was probably an unfulfilled musicologist: she had a million songs rattling about in her head, and would regularly remember an old Slavic tune she had learned as a child in great detail. We did not have classical music in the home until I brought it myself, but the Polish-language radio stations regularly played Chopin as a point of pride, and that was probably my first exposure. That, and the singing of old songs during the liturgy: unlike American parishes, whose Novus Ordo had devolved into cheap imitations of popular music and sacro-kitsch, the Polish parishes fell back on their traditional devotional folk music, which was often quite beautiful in its own way.

IACS: Fill us in a little about how you got from growing up in Chicago to becoming a composer?

Nowakowski: I think I took a bit of a round-about path compared to lots of professional composers out there, though such non-standard backgrounds are much more common amongst student composers today. If you asked me in the third grade about music, I’d tell you: “I hate music.” This is because I thought “music” meant “pop music.” I abhorred pop music — and in large parts still do — for a number of reasons: even as a child I found it to be odd, posturing, manufactured, shallow, and able to make people move and behave in strange and unseemly ways. MTV struck me as the most bizarre thing: I could not fathom what the attraction was. Then during the fourth grade, a traveling string quartet from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra came to our school. Most of my classmates giggled at the strange movements and visual language of the display, but I — lucky enough to be sitting cross-legged right by the first violinist — was absolutely entranced. Suddenly, I knew that music was much more than the pop glitz everyone was addicted to, and I wanted more of that deeper experience. The next year I was able to pick up the saxophone and join the school band, while later I attended St. Laurence High School, where Leo Henning (a former Sinatra musician) and his son Patrick ably led a quality wind ensemble program. This was where I learned (or mostly failed) my first attempts at music theory, and also got my first opportunities to put note to page. While I resisted the pull, I finally became a composition major during my fourth semester of college, and have never looked back.

MTV struck me as the most bizarre thing.

IACS: How does your Catholic faith influence your work?

Nowakowski: I cannot ultimately understand music or my role as a composer without Christ, while the aesthetic magisterium provided by the Catholic Church gives me an immense treasury to draw upon and a vital standard against which to measure my work. Not only that, but the Catholic understanding of Beauty as a self-revelation of God (and the classical and patristic-era notions of music as a key aspect of existence itself) places the composer’s role firmly into that of “vocation.” John Paul 2’s Letter to Artists further inspired me and gave me direction as an artist, along with his notion the “The Church needs Art, and Art needs the Church.”

I cannot ultimately understand music or my role as a composer without Christ

IACS: From your perspective, what role does beauty play in the Catholic faith — and in your work as a composer?

Nowakowski: Just as we differentiate between “small t” and “large T” tradition, I think the Church implicitly also manifests an experience which can help us delineate between “small b” and “large B” beauty. Small “b” beauty would be a subjective statement, a pointing to something which we think may have quality and (in St. Thomas Aquinas’s words) bring delight: it is a statement of opinion. Yet “large B” Beauty is a concrete label, as Beauty itself is ultimately an objective reality which is the self-revelation of God. Every great artist, whether they are believers or not, struggle uphill mightily in pursuit of Beauty as an objective reality, and – falling short – know both its great promise and its impossible standard. In essence, an artist of any stripe who reaches for the great reality of Beauty will never succeed, and therefore always has his eyes upon the everlasting hills, where Beauty beckons to a greater reality beyond this mortal coil.

IACS: What attracts people to beauty — particularly beauty in music?

Nowakowski: One of the transcendentals must always speak to society. In our age, where people do not know the western – let alone the Catholic – intellectual tradition, and where what constitutes “goodness” is under volatile debate, the objectivity of true beauty provides an entry point into conversation with the divine. I think of all the otherwise cynical agnostics and atheists who are staring in mute wonder at beautiful work of sacred art or architecture somewhere in the world at this very moment, or have a nearly religious reverence for the work of Bach, or perhaps draw spiritual sustenance from the modern music of Arvo Pärt. Beauty is able to draw us outside of ourselves, and those who worship at her altar are already one third Catholic without perhaps realizing it. To perceive the objectivity of Beauty – and encounter its humbling and shattering power – is to be pointed in the direction of home.

Beauty is able to draw us outside of ourselves, and those who worship at her altar are already one third Catholic without perhaps realizing it.

IACS: What role do the arts play in the academy? In the church?

Nowakowski: We’re in a strange paradoxical place where our culture is losing its heritage, even as the number of students majoring in the arts has never been higher. Yet secular art formation is generally corrupted by various flavors of modernism and relativism, while explicitly Catholic forms of arts education are almost entirely lacking in necessary theological and aesthetic formation. In the field of music this is a particularly strange situation, because what we think of as music composition – writing note-against-note onto a visual score – is really an invention of Christendom. Furthermore, even amongst modern composers in an often anti-religious environment, Catholicism plays an immense role: From Palestrina to Messiaen, we have an unbroken line of profound Catholic composers spanning the centuries. The 20th century’s most profound composition pedagogue, Nadia Boulanger, was a daily communicant. Henryk Gorecki, a devout Polish Catholic, wrote the best-selling symphony of the 20th century. And today, two of the world’s most frequently performed composers – James MacMillan and Arvo Pärt – are Catholic and Orthodox respectively. And with all of this, not a single American institution teaches music composition – not just liturgical composition, but music composition in general – with a Catholic focus. It’s an immense blind spot which must be remedied. The good news is that despite lacking institutional and ecclesial support, the Catholic music composition world is still flourishing with a new movement of composers, and it would not take very much at all to give this movement an official institutional home. In general, the work done by groups like the Catholic Art Institute in Chicago and the Benedict XVI Institute in San Francisco bring artists together and promote wonderful work: we can only imagine how quickly we’d have a renaissance if more patronage and ecclesial support could be found!

IACS: Tell us a bit about composing and your writing process.

Nowakowski: Somebody asked me about this yesterday, and I was surprised at how difficult it was to formulate an answer. I suppose it is a bit like the classical “so what kind of music do you write?” question, which often trips up composers. As to me, I suppose I just have to live with an idea, and let it take shape in my imagination. At a certain point I’ve learned to intuit when it is no longer too fragile to be handled, and I began to work it out on the written page. I suppose that often composers will write a great deal of music and work through ideas, searching for the one theme or fragment which then becomes “the way in” to a larger expression. It’s not uncommon to write many pages of music until the right turn of phrase or little progression is found, at which point one may use this to enter the world of the work which does not yet exist. Yet as John Paul 2 wrote in his Letter to Artists, the gap between what we glimpse in our spiritual imagination and what we can succeed in bringing down to show to others is often quite vast.

IACS: What projects do you have in the works?

Nowakowski: I’m scoring a short film called “Agoniya” by the talented young director Aaron Kessler, and then moving on to score the last part of the Mass of the Ages trilogy. In the fall I’ll be on sabbatical completing my “Symphony of Sacred Songs” for Orchestra and Mixed Choir. Finally, I just completed my second CD – Metanoia – and pre-sales have just begun. I’m very excited about this last item, as Metanoia musically represents the last decade of my creative endeavors in a variety of genres – small and large chamber music, sacred works with voice, a choral piece, and even a piece with cello and electronics that I think will surprise listeners who are skeptical of such efforts. The title track, Metanoia, is composed for cello octet, and it is an aural description of the word: the great journey of prayer and life change necessary for a true personal Metanoia, or a “change in one’s thinking” in the most profound sense. I hope the music contained therein can be a companion to the spiritual journeys, struggles and victories of those who listen.

Editor’s note: Pre-order Mark Nowakowski’s new album “Metanoia” at: https://naxos.lnk.to/DUX1916