COVID-19 and Black Immigrants: The Pandemics of Racism, Nativism, and Transnational Crises

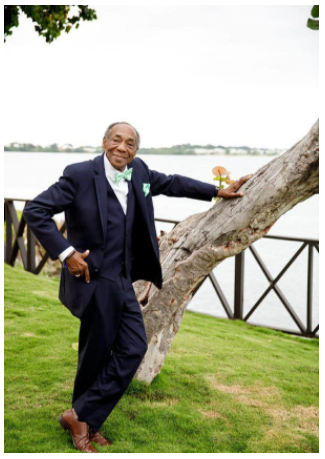

The loss of life in the Black community in New York is one of the greater obstacles families and communities continue to grapple with as a result of COVID-19. The passing of Conrad Ifill, for example, sent a shockwave throughout the Caribbean community in New York. In March 2020, COVID-19 gripped New York, making it the new global epicenter of the virus. Mr. Ifill was an 81-year-old Black immigrant from Trinidad and Tobago. He lost a multi-week battle with COVID-19. Mr. Ifill came to the U.S. in the 1970s and established a family-run business – Conrad’s Famous Bakery – which served the Caribbean community in East Flatbush, Brooklyn for over 30 years. Clerge’s Facebook friend, Dante walked by local businesses in Brooklyn and saw a poster honoring Mr. Ifill’s life. Dante posted an image of the flyer, adding the caption “COVID-19 is an assassin.”

[Photo source: Matthew Ellis (NYT). “Conrad Ifill, seen here in 2019, left his Wall Street job as a data processor to open his own business.”]

COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted Black and brown communities in the U.S.; as they exhibit higher rates of infection, hospitalizations, and deaths, and unequal access to vaccinations (see graph below). Behind these numbers are the lives of people like the Ifill family – immigrants from the Caribbean, Latin American, and African countries who are one less or managing lingering COVID-19 symptoms. Although the discourse on racism and COVID-19 treats Black families as a homogenous group, Black immigrants are experiencing a unique set of challenges such as deportation and remittance strain. These transnational migrants are managing the global pandemics of COVID-19 and anti-Black racisms, not only here in the U.S., but also in their home countries.

Source: NYC Department of Public Health (https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-totals.page)

How COVID-19 Impacts Black Immigrants in the U.S.

There are 4.2 million Black immigrants in the U.S. and they make up 10% of the Black population. They largely live in states most impacted by COVID-19: New York Florida, Georgia, and D.C. South Florida and New York have the largest concentrations of Black immigrants. These have also been COVID-19 hotspots. In New York, Black patients were more likely to test positive for COVID-19-19 than whites, however, they only make up a small percentage of city residents who have been vaccinated. New York has a large population of Afro-Latinx immigrants, totaling 273,952, according to the American Community Survey. Many hail from the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Panama Therefore, both non-Hispanic and Hispanic Black immigrants have contracted COVID-19, yet, these distinctions are largely obscured by racial data collection practices in hospitals and testing sites.

Although all Black people in the U.S. are encountering severe political and economic problems due to COVID-19, the inequalities are all the more complex for Black immigrants who have a liminal position in the U.S. They are subject to additional measures of containment, surveillance, and detainment, and hold the economic security of their home countries in their hands.

Essential Workers

Black immigrants live in a web of anti-Black pandemics that preceded COVID-19 and have now been compounded by it. The U.S.’s racially segregated and unequal labor force is one important example. Black immigrants are concentrated in essential worker occupations such as transportation and healthcare. Although scholars refer to these as niche occupations or ethnic economies, we see the concentration of Blacks, in general, and Black immigrants, in particular, in occupations rooted in racial capitalism (Robinson, 1983), or the organization of labor, property, and land around white imperial and colonial domination. For example, pre-pandemic, Black immigrants had the highest rates of unemployment compared to other immigrant groups, 9.9%. Black immigrants encountered significant anti-Black racism in the job market, leading many to seek work opportunities in healthcare professions to find economic empowerment. However, these professions have also made them vulnerable to COVID-19 exposure.

Hazel, a participant in Clerge’s research on Black middle-class New York, is a Jamaican immigrant in her 50s who contracted COVID-19 at the nursing home/rehabilitation center where she works as a nurse in April. Hazel arrived in the U.S.in the 90s. She aspired to work in the financial sector. However, after repeatedly being passed over for promotions at a Jewish company in New York, she heard from a friend that there was less bias and a need for workers in nursing. Hazel recovered from COVID-19 in June, only to contract it again on her job. She has a lingering, and sometimes debilitating cough, and ongoing blood clotting in her legs. She’s reluctant to reduce her work hours because her family relies on her to cover the cost of the mortgage. In addition to housing and living expenses here, she is also responsible for sending money back home to support family members in Jamaica.

Status and Deportation

Black immigrants also face the reality of deportation, partly because many work in essential occupations. The public exposure that these occupations subject them to leads to the increased likelihood of interacting with local police and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents.

As Black Lives Matter protests exploded across hundreds of cities in the U.S. and abroad in 2020 to protest the senseless murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, the encounters of state–sanctioned surveillance and violence are felt acutely by Black immigrants. Although the face of deportation is more often that of Latinx immigrants, Black immigrants make up an important segment of the detained and deported population. In 2013, sixteen percent of the Black immigrant population was undocumented. In 2017, Black immigrants comprise 7% of the undocumented population, yet 20% of those facing removal proceedings.

Prior to the pandemic, ICE was raiding Black immigrant communities and targeting Black immigrant businesses and ICE has continued to detain and deport Black immigrants during the COVID-19-19 pandemic. In May, ICE continued deporting detainees to Haiti, many of whom hadn’t lived in Haiti since they were young children. More recently, Haitian migrants at the U.S. Mexico border have been detained and deported in larger numbers under the Biden administration. They were exposed to COVID-19 while in detention centers, leading activists to call out the Trump administration for spreading the virus across borders. The U.S. government continues to raid immigrant communities, detain people into overcrowded prisons and centers that are key sites of COVID-19 spread, and deport non-citizens even if they test positive for the virus, thereby compromising the global virus containment efforts and health care systems of immigrant’s home countries.

Crises of Remittances

Black immigrants are not only dealing with the COVID-19 crisis in the U.S., but they are also concerned with how the pandemic is impacting their families back home. Black immigrants are remaining tied to the unfolding political and economic conditions of their home countries during the pandemic. Transnational technologies such as Whatsapp phone calls, Facetime video chats, and online calling cards allow Black immigrants to stay connected to the happenings in their families and news media in their home countries.

From the Bahamas to Panama, Caribbean countries are in economically precarious positions induced by the virus, and there is wide variation in how governments are managing quarantine, the local economy, and now, vaccine distribution. For example, as of November 22, 2020, the number of confirmed cases ranges from 137,770 in the Dominican Republic to 19 in St. Kitts and Nevis. The death toll ranges from 2,308 in the Dominican Republic to zero in Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts, and Nevis, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. But one thing is for sure: Despite how well some Caribbean countries have managed to contain the spread of the disease and minimize fatalities, the economic future is uncertain, which may result in greater pressure to migrate or for remittances. A significant portion of the GDPs of Caribbean countries relies on remittances from family and friends who reside in the U.S. According to the World Bank, Latin America and Caribbean countries received $9.5 billion in remittances in 2019. Before the pandemic, the Dominican Republic received the most remittances, roughly $7.4 billion in 2019. Haiti, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago totaled 3.2 billion, 2.5 billion, and 143 million, respectively. These remittance flows have been compromised by the U.S.’s expanding economic and hunger crisis.

The disproportionate loss of life and disability in Black and immigrant communities have stolen household earners who were key caretakers of their families in the U.S. and in their home countries. In 2020, a net of 9.8 million jobs was lost due to the pandemic, many of which were in the service sector of the economy. Quarantine mandates and widespread illness of immigrant workers like Hazel who are now struggling with long COVID-19 disabilities are not only compromising the lives of workers and their families here in the U.S. but also undermines their ability to take care of their transnational families and communities abroad just as economic pressures increase.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In December 2020, Sandra Lindsay, a Jamaican immigrant nurse at Long Island Jewish Hospital in New York was the first person in the U.S. to receive the Moderna vaccine. As the Biden Harris administration’s response to COVID-19 and the vaccine rollout are underway, their agenda must address the intersectional experiences within and between Black and immigrant communities who are managing the trifecta of a Jim Crow carceral system and immigration enforcement, economic insecurity as both essential and non-essential workers, and the ripple effects emanating from economic instability of their countries of origin, whom Black immigrants keep afloat with remittances.

Since Black immigrants are overwhelmingly represented in essential industries, a successful vaccine distribution will save lives. However, the vaccine is not the magic cure for generations of systemic anti-Black and anti-immigrant racisms. Since Black Lives still do not matter in the medical, occupational, and carceral US state, how Black peoples in general and Black immigrants, in particular, will be protected remains in question. Will the legacies of scientific racism continue to undermine the ability of Black people to trust the vaccine? Will Black immigrants who have been brutally detained and imprisoned receive the protection from COVID-19 they need to save their lives? Will the government meet the needs of families by providing a regular supply of PPE and monetary assistance?

COVID-19 has laid bare the compounding impacts of racism and anti-immigrant practices. A close look at the lives of Black immigrants demonstrates the fine dance they must do while living between two worlds gripped by the pandemics of anti-Black racism, COVID-19, and neoliberal racial capitalism.

About the authors:

Orly Clergé is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at UC Davis and her research focuses on race and racism, migration & immigration, cities, and cultural identity.

Zophia Edwards is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Black Studies and Director of Black Studies at Providence College. Her areas of research and teaching include postcolonial sociology, colonialism, labor movements, race, international development, and political sociology. Her public scholarship can be found in Monthly Review, National Workers Union (Trinidad and Tobago) website, among others, and her research has been published in Political Power and Social Theory, The Sociological Review, Studies in International Comparative Development and more.

© 2021. This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.