Scholars gain insight from the geographical and cultural movement of artifacts

When preserved specimens of birds of paradise — prized throughout 17th-century Europe for their vivid plumage, rarity and distant origins — were exported from their native Papua, New Guinea, by the Dutch, their feet were routinely cut off for transport. Thus, many Europeans who viewed the footless specimens concluded that these exotic creatures must remain in constant flight as they possessed no feet with which to land.

This fascinating observation appears in a collection of 12 essays, each devoted to a different object that traveled across distances and cultures in what historians call the “early modern period”, roughly 1500–1800. The collection first appeared as a special issue of the peer-reviewed scholarly journal Art History, titled Objects in Motion in the Early Modern World. Published in September, the special issue of the highly respected academic journal was coedited by USC Dornsife’s Daniela Bleichmar, associate professor of art history and history and director of the Visual Studies Graduate Certificate, and Meredith Martin of New York University. The essays will be available in book form from Wiley in 2016.

Exploring culture and the past

The Art History issue grew out of the USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute (EMSI) Annual Conference, “Objects in Motion in the Early Modern World.” Hosted by The Getty in May 2013, the event was organized by Bleichmar, who also is associate provost for faculty and student initiatives in the arts and humanities, as well as Martin and Joanne Pillsbury, then of the Getty Research Institute.

Daniela Bleichmar, associate professor of art history and history and director of the Visual Studies Graduate Certificate at USC Dornsife. Photo courtesy of the USC Office of the Provost.

“We were interested in thinking about how the current scholarly interest in globalization, mobility, and cultural exchange impacts the major narratives of early modern art and history,” Bleichmar said. “We wanted to ask, ‘What are the larger implications of this line of inquiry for the study of the early modern period, and for art history as a discipline?’”

The conference brought together an international group of scholars to examine the circulation of objects across regions and cultures in the early modern period, addressing the ways in which mobility led to new meanings, uses and interpretations. Topics included the diplomatic exchange of gifts among the Ottoman Empire, Europe and South Asia; the transfer of luxury goods between Japan and Mexico; and the reception of Persian ceramics and other foreign imports on the Swahili Coast of East Africa; among others.

“Recently there has been great interest in what objects, or material evidence, can tell us about culture and the past,” Bleichmar said, citing The British Museum’s hugely popular and influential project “The History of the World in 100 Objects,” which used objects from its collection as a launching pad to talk about human history.

“We thought that people who work on art and visual and material culture – fields that have long been interested in objects –have much to contribute to this conversation. Academic conferences usually tend to be narrowly focused geographically; we wanted to explode that and invite scholars working on many different regions of the world. We wanted to show how those regions were not, in fact, isolated, but were making contact and exchanges; that circulation and long-distance connections are not exclusively contemporary phenomena but have a long history.”

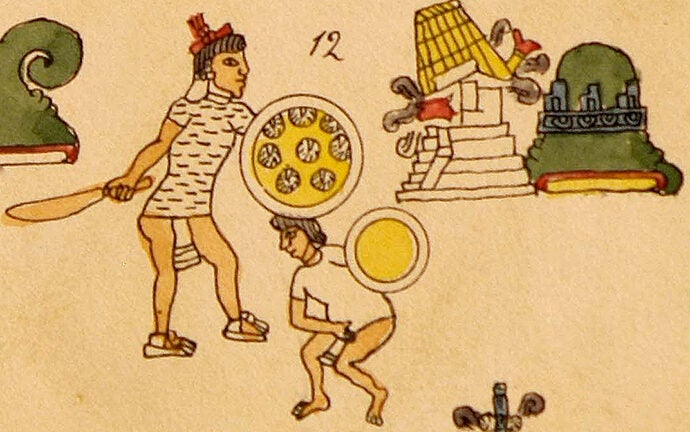

The cover of the September issue of Art History, co-edited by Daniela Bleichmar.

The 12 essays that appear in Art History explore the ways objects were transported, translated, resisted and consumed in the early modern period. They focus on issues such as how mobility affected cultural meaning, the role environment or context played in an object’s fixity or mutability, and the kinds of cultural meanings that tended to travel with an object, as well as those which were lost in transit. The scholars also explored the ways in which objects shaped or altered an understanding of the cultures from which they derived as well as the practices and beliefs of the new environments into which they were placed.

Revealing an Aztec literary treasure

Bleichmar’s own essay explores the Codex Mendoza, an Aztec codex created ca. 1542, that is, only 21 years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521.

“This very early book, now housed at the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford in England, includes both European and Aztec elements and is widely considered to be incredibly important,” Bleichmar said. “It’s a fascinating object that was made at a very specific moment of cultural exchange and has been traditionally linked to the first viceroy of Mexico, Don Antonio de Mendoza, the most powerful representative of the King of Spain in Mexico.”

The original Aztec images in the Codex Mendoza were translated into Nahautl, the indigenous Aztec language, and from that into spoken Spanish before finally being written down.

The book was made for export to Europe and was intended to go to the Spanish court. However, it somehow ended up in France—the French royal cosmographer claimed it had arrived there after being stolen by pirates—and then repeatedly changed hands and moved from one location to another until it entered the library in 1659. After that, its contents continued to circulate in print as a reproduction: ten different books published between 1625 and 1813 reproduced portions of the original manuscript, changing depictions and interpretations each time.

The book was first made first by Aztec artists who painted the images according to their traditions. These images were then turned into a spoken narrative in Nahuatl, the indigenous language of the Aztecs; which was in turn translated into spoken Spanish; and in a final step written down.

“I became interested in different kinds of circulation, the idea of translation and how people made meaning of different cultural translations,” Bleichmar said.

“I’m curious about how Aztec artists, who have pictorial, but not alphabetic, writing made sense of European books and how Spaniards made sense of Aztec writing. I also wanted to explore how European scholars understood objects from Mexico and how scholars throughout the early modern period were making sense of what this manuscript meant and constantly translating and transforming it.”

The book is divided into three sections, the first of which focuses on the history of the Aztec Empire; the second on the tribute — the tax paid by all towns belonging to the Aztec Empire; and the third on aspects of society and life from birth to death.

“It’s a cultural encyclopedia,” said Bleichmar, who is writing a book about it. “It’s mind-blowing. And the experience of putting together Objects in Motion, of working with eleven other scholars who were examining parallel objects in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas, made clear how much great new work is emerging and how much humanists gain from collaboration. Scholarship is full of discoveries and excitement.”