Addressing Perception

A couple on the tiny Hebridean island of Colonsay in Scotland were planning their wedding earlier this year when the bride’s mother sent her daughter a photograph of the dress she planned to wear. When the bride showed the picture to her fiancé, the pair could not agree on what they saw.

To the bride, the dress was white and gold. The groom, however, saw blue and black. The couple posted the image on Facebook, asking friends to settle the dispute. Little did they guess that they would set the Internet alight, sparking one of the biggest social media conversations of 2015.

The debate rapidly went viral, as differing perceptions split friends, families and co-workers.

“The image of the dress triggered such a global furor because it challenges our seemingly self-evident and unquestioned assumption that we see the world as it really is, thereby raising questions about perception and reality,” said Bosco Tjan, professor of psychology and an expert on visual perception.

Why do our perceptions differ? What does this say about the way we view the world? USC Dornsife psychologists consider these questions, looking also at how our perceptions are affected by those closest to us and examining some of the most extreme cases of differing perception — those rooted in schizophrenia, eating disorders and dementia — while giving their views on the question: Does an objective reality exist?

But first, back to the dress: Why do people see it differently?

“Perception is about how your brain interprets your sensory input,” said Tjan. A founding member and co-director of the USC Dornsife Cognitive Neuroimaging Center, Tjan studies the human visual system; in particular, the neural computations that underlie the perception of form.

“Our perception of color depends on our perception of the light in a room or scene,” he said. “When cues about ambient light are missing — as was the case in the photograph of the dress — people may perceive different color for the same object because they implicitly make different assumptions about the ambient light.”

This is because color, or more precisely “reflectance,” is a physical property of the material — how much light it reflects at different wavelengths, Tjan explained. A red object, for example, reflects more long-wavelength light than short-wavelength light. Our eyes cannot see reflectance (the color of an object). Instead, we see the light that the object reflects. In order to infer the color of an object, we need to know the color of the light shining on the object, or more precisely, the wavelength or spectral distribution of the light. In the case of the dress, we may make different assumptions about the time of day at which it was photographed, and hence assume a different color of the light.

“The brain is always working to infer information, and if it doesn’t have access to direct information, it makes assumptions,” said Tjan, whose work addresses questions pertaining to vision loss, restoration and rehabilitation, including object and face recognition, reading, attention and visual navigation.

“Different people’s brains make different but equally reasonable assumptions. Perception is not direct; it is an implicit or unconscious inference process. Our brains are constantly solving these problems for us behind the scenes, very quickly.”

The fact is that humans, like all organisms, are simply not equipped with sufficient sensors to eliminate all ambiguity to directly perceive our world, without assumptions.

“Instead, the brain relies on the fact that our world is governed by physical principles to compensate for our inherently limited and incomplete sensory input and make decisions about what we are really dealing with,” Tjan added. As we have to fill in the gaps with what we know about the world — something that varies according to each individual’s experience — there is room for error and diversity.

What is not present in the photo — in this case the light source — forces our brains to infer the color of the dress from the imagined color of the light source, which influences how we see the dress. Our brains make the decision for us, unconsciously about the color of ambient light and consciously about the color of the dress, and once it has done so, we see it that way.

“The pairing of the colors in the dress materials turned out to hit just the right spot where assumption about daylight matters a lot for seeing the colors of the dress,” Tjan said.

Shaping emotional and social perception

Perception of the world is not limited to the visual, but is also rooted in the way we experience it emotionally. Much of our emotional — and consequently social — perception is influenced by our earliest experiences, as well as by those people closest to us.

“Perception doesn’t emerge fully formed on our first day of life. It is shaped,” said Darby Saxbe, assistant professor of psychology. Saxbe’s research focuses on how early experiences frame the development of emotion regulation, stress response and social perception, and how these phenomena influence subsequent psychosocial functioning.

“I’m interested in how nature and nurture intersect,” she said. “Our perceptual lens, our way of appraising situations, is influenced by our earliest experiences.

“How we start to form perceptions is very much in coordination with a caregiver. Infants start to figure out how the world makes sense by perceiving patterns through this coregulation with a parent on everything from sleep, emotion, temperature, feeding, circadian rhythms, and so on.”

These early influences continue into childhood and adolescence, Saxbe found. Children raised in families that experience more trauma and adversity make different appraisals of social situations when they reach adolescence compared to those who grew up in more peaceful households.

Saxbe gives the example of a neutral situation where one high school student says to another, “The teacher wants to talk to you after class.”

“One student might think, ‘Oh, maybe I’ve won an award,’ and another might think, ‘I’m going to be expelled,’ ” Saxbe said. “Our perception of reality is shaped by our history.”

That perception may also go some way toward creating our realities.

How we see the world — and particularly our emotional and social perception — is influenced by our earliest experiences.

“If you have experienced a lot of trauma, then you might have more negative attributions and expectations. That, in turn, can shape how people are going to react to you because if you have negative expectations you might also be more hostile or aggressive.”

Saxbe cites a study by researchers at Northwestern University and the University of Pittsburgh showing that teenagers are more pre-emptively aggressive if they make negative interpretations of other people’s behavior. Thus, if a high school student from a nonaggressive family is jostled while walking down a hallway, he will probably conclude itwas an accident. However, someone with a lot of hostile expectations might assume the action was deliberate and want to start a fight.

“Here we have a case where someone’s history is creatinga perception, and that perception is then creating or reinforcing their reality because they may react aggressively, and so that perception will become a very negative, hostile reality,” Saxbe said.

Her research suggesting that our perception of reality is not formed in isolation but is clearly influenced by those closest to us — often spouses and parents — was borne out by her studies of cortisol.

Saxbe found that couples share similar patterns of the stress hormone, suggesting they pick up on each other’s negative affect or stress.

“So when our partner is experiencing a lot of stress, we might start to view the world through their eyes and display some of the same physiological stress patterns they are showing,” she said. “We link up with people we are close to, not just in a conscious way, but also physiologically, and we even start to share a common way of functioning biologically. These findings certainly fit with the idea that our social context really shapes who we are and our own frame on the world.”

The way in which perception can shape reality can also be seen in those suffering from depression who are convinced that people do not like them. “That perception becomes self-perpetuating because if you are somebody who isn’t friendly, then people don’t want to be around you,” Saxbe said. This is an oft-occurring factor in mental illness, and many cognitive behavioral therapies — which focus on examining the intricate links between thoughts, feelings and behaviors to help people improve their lives and reduce suffering — are built around trying to combat this type of mental distortion.

Entering the realm of the unreal

Like Saxbe, Shannon Couture, assistant professor of the practice of psychology and director of the USC PsychologyServices Center (PSC), is interested in the intersection between social relationships and well-being. Couture’s research explores social cognition and its link with social functioning and behavior in schizophrenia. She is the author of numerous studies on the mental disorder, mostly focusing on understanding factors that underlie the social functioning deficits frequently documented in schizophrenia.

Couture is also responsible for the day-to-day running of the PSC, which serves as a teaching clinic for USC doctoral students earning their Ph.D.s in clinical psychology. The center provides individual, group, couples and family treatments as well as psychoeducational and neuropsychological assessments. Most clients have depression, anxiety disorders and other life difficulties such as relationship or occupational problems.

Couture’s wider clinical experience has made her familiar with the distorted perception that can occur in people with anorexia nervosa who may develop unrealistic body images.

“To bring this home to patients, therapists often ask people with anorexia to draw their body outline on a wall,” said Couture.

The therapist will then trace around the patient’s actual body to show how the patient’s perception deviates from reality.

“Usually patients draw themselves several inches wider than they actually are,” said Couture, who supervises Ph.D. students as they learn how to conduct therapy sessions.

While depression and eating disorders can cause distortion in perception, those suffering from schizophrenia — a mental disorder often characterized by failure to recognize what is real — may truly find themselves in the realm of the unreal.

Disturbances in sensory perception can be seen in individuals with schizophrenia, 50 to 80 percent of whom experience auditory hallucinations, according to a 2007 review of the literature by Thomas McGlashan at Yale University.

“During these episodes they perceive voices, sounds or music that do not exist in reality,” Couture explained.

So why does this happen?

That, said Couture, is the million-dollar question.

“In some cases, the content may be similar to a conversation or traumatic event the individual with schizophrenia may have experienced in the past. One theory is that those types of auditory hallucinations may be related to memories being triggered, but the person is not experiencing them as a memory.”

Other types of auditory hallucinations are not associated with the past but feature voices commenting on what a person is doing in the present moment.

“Psychologists think those types of voices may be more related to inner speech, such as talking to ourselves or imagining having a conversation with someone else,” Couture said. “Neuroimaging shows that parts of the brain activated in normal individuals engaged in those activities are also activated in people with schizophrenia experiencing auditory hallucinations.”

Individuals with schizophrenia can also experience tactile hallucinations, in which they might feel insects crawling on their skin, or olfactory hallucinations, in which they report smelling odors that are not there.

According to a 2014 study published in Schizophrenia Bulletin, between 15 and 40 percent of people with schizophrenia also experience visual hallucinations. These can manifest as distortion of perception, Couture said, so that an individual with schizophrenia may perceive an advertising slogan on a billboard or a newspaper headline as changing into words that have personal meaning. Those with schizophrenia may also experience full-blown visual hallucinations in which a person who is not there is experienced as being present, although these tend to be more rare.

When dementia distorts perception

Individuals with schizophrenia are not alone in experiencingepisodes of distorted perception in which they believe someone is present who is not.

“People with dementia may see some sort of shadow and think there is someone in the house,” said Margaret Gatz, professor of psychology at USC Dornsife and an expert on aging and Alzheimer’s disease. “This may sound similar to a visual hallucination of the type observed in people with schizophrenia, but in the case of dementia it’s very limited and specific and caused by trying to make sense of a neural signal that has become confused.”

A 2010 National Public Radio report on dementia featured 87-year-old Emmorry Jackson, a former carpenter with Alzheimer’s disease, who found pleasure in using imaginary tools to “mend” a chair he falsely perceived to be broken.

“Perceiving the chair to be broken is another example of mistaken perception caused by dementia,” said Gatz, who also holds joint appointments in gerontology from USC Davis School of Gerontology and in preventive medicine from Keck School of Medicine of USC.

“When people become demented or develop some kind of neurocognitive disorder, the functions that most people think about being impaired are mostly related to memory,but in fact many aspects of the brain are affected in different ways.”

One early sign of dementia is faulty spatial perception, which often results in minor fender benders. “It’s not infrequent to see people having trouble getting through the garage door or hitting another car in a parking lot,” said Gatz, who codeveloped Forgotten Memories, inspired by a fotonovela — a small pamphlet akin to a comic-book, with photographs combined with dialogue bubbles. Targeted at the Latino community, it aims to inform its audience about the early signs of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia and encourage action. An audiovisual version of the original fotonovela recently aired on PBS.

With severe dementia, temporal perceptions also get muddled and the likelihood of confusing family members of different generations is increased. “Remembering the immediate present and the long past are OK, but everything in between is problematic,” Gatz said.

A subjective lens through which to view reality

People don’t need to be suffering from mental disorders as extreme as schizophrenia or severe dementia to experience distortion of reality. Couture notes that many people also hear voices who do not have any psychiatric diagnosis, while people with social anxiety may experience distorted perception.

Schizophrenia can cause disturbances in sensory perception, including auditory or tactile hallucinations that may cause patients to hear voices, music or sounds that are not there, or to feel insects crawling on their skin.

“We see distorted recollections of events in people with social anxiety because they pay attention to cues that people are rejecting them or judging them,” Couture said. “When you’re constantly looking out for those cues, it distorts your perception because you’re not observing the big picture. Instead you’re looking for something that’s consistent with your own issues.”

Couture argues that we probably all experience somewhat distorted perceptions of our world. “This is because we process our perceptions through memory, which is impacted in turn by the subjective lens through which we each view reality,” she said.

She sees this when couples come in for therapy and want to discuss the same argument, yet have totally different perceptions of what happened. “There are many shared features, of course — we don’t have drastically different perceptions of the world — but because we are inundated with information, we all attend to specific facets of what is going on around us and that affects our perception of the world.”

Gerald Davison, professor of psychology who holds a joint appointment at USC Davis School of Gerontology, concurs. “We basically confirm our own predilections,” he said. An expert in mental health, Davison is the author of more than 150 publications, including Abnormal Psychology (John Wiley and Sons, 2016), a seminal undergraduate textbook, used globally, that explores perception-altering mental disorders such as schizophrenia. His research employs a think-aloud method that enables study participants to verbalize their thoughts and feelings as they imagine themselves in complex interpersonal situations. In this way, he has been able to explore how people construe events that are open to different interpretations.

“People bring into any situation a series of assumptions about what the world is like, and these assumptions, or paradigms, drive and heavily influence how we end up perceiving that situation and how we react to it. Even things that appear to be something everyone could agree upon — what we call consensually agreed-upon reality — can often be perceived differently, depending on a variety of different circumstances.”

Davison cites an example he often uses in undergraduate classes.

“You can look at a pencil and simply see a pencil. But if I hold it aloft and point it at you, you may perceive it as dangerous. If I do that and also tell you this pencil is a device equipped with a gas canister that was used during World War II to fire a mace-like substance at the enemy, you would probably feel threatened.”

One example of the way our perceptions can play tricks on us lies in our built environment.

“Our cultural experiences guide us into thinking that doors and windows are rectangular, even though our retinas do not show them as such,” Davison said. “We can be fooled into thinking that everything that is a door is necessarily rectangular.”

However, some architects, such as Frank Gehry, manipulate this by constructing forms that are intentionally not rectangular.

“Gehry’s architecture plays with forms and tricks you into thinking a thing is a certain shape when it really isn’t,” Davison explained. “Taking advantage of the way we think the world is constructed can be an effective tool to get our attention.”

So is it possible to know whether there is an objective reality?

While he maintains that the way we construct our realities is governed by individual perception that can depend upon a whole host of factors, including our moods or even whether we are hungry, Davison argues that it would be illogical not to assume that some objective reality exists.

“We live in a physical universe and share certain consensually validated beliefs about what the world is like,” he said. “Without that, it would be chaos.”

Couture agrees.

“As a society and in our relationships we tend to agree on some sort of shared perception of what is going on,” she said. “But the only way we could really know for sure is by recording everything and reviewing it. Even then we would be constrained by what is being attended to, which direction the camera is pointed.”

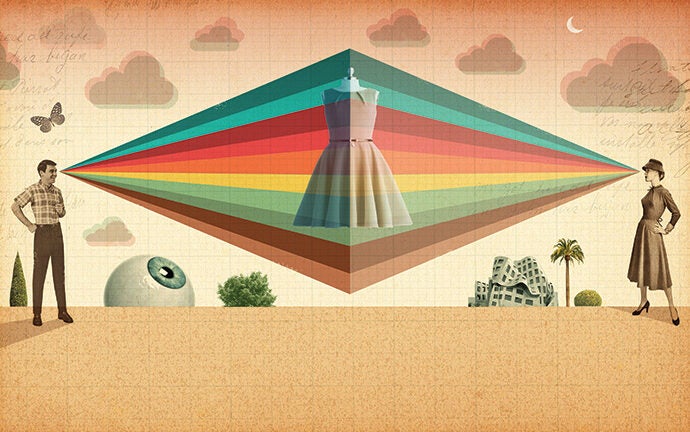

Illustrations by Michael Waraksa for USC Dornsife Magazine

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine‘s Fall 2015-Winter 2016 issue >>