Rewriting Photographic History

Nadya Bair has long been entranced by photography. As a child in Moscow, she can remember her grandfather — an aerial photographer during World War II — developing photos in his kitchen. The materiality and abundance of photography, she said, was always part of her life.

But she is equally entranced by the social history of the medium. Living in a time when photos are ubiquitous and anyone with a phone is already a photographer, it’s easy to forget that 65 to 70 years ago, “people still needed someone to work through the world for them photographically,” Bair noted.

In the 15 years following WWII, innovations in visual culture occurred on a grand scale. This transformation became the topic of Bair’s doctoral dissertation, “The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Art of Collaboration in Postwar Photojournalism.”

Newfound purpose

In a sense, the war was the fire that fueled the proliferation of photojournalism in the middle of the 20th century. War photographers commanded handsome fees for documenting the conflict around the world for newspapers and the booming illustrated magazine industry. The general public came to recognize and depend on photojournalistic documentation of global events.

And then the war ended.

“After making a reputation for themselves covering WWII, the most important moment in the careers of these photojournalists was over,” Bair said. Transitioning to peacetime challenged them to find new applications for the photographic medium and to make their pictures as moving and marketable as they were during the war.

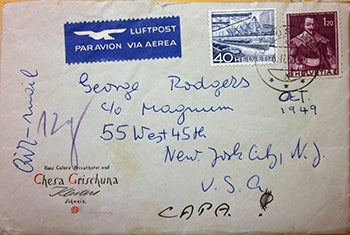

Magnum photographers used everything from telegram to express mail to coordinate story assignments and stay in touch with their clients and each other on a daily basis. Here, an envelope containing a letter from Robert Capa to another Magnum founder, the British photographer George Rodger. Images courtesy of Nadya Bair.

One group of photojournalists responded to this challenge by establishing Magnum Photos in 1947. Including such photographic luminaries as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa, the cooperative soon became known for its international focus and the trademark editorial style of its photo essays and human interest stories.

According to Bair’s research, the innovative nature of Magnum Photos pushed photographic news — both as an aesthetic and a mode of production — into new markets in the 1950s, shaping the visual representation of everything from tourism and Hollywood film sets to the work of relief organizations and business corporations.

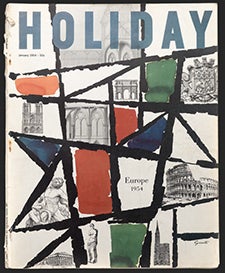

Magnum Photos shot many stories for the American travel magazine Holiday that blurred the genres of news and travel photography. For this 1954 issue, Magnum photographers covered almost all of Europe to show that the continent had recovered from World War II and was ready for American tourists.

“Magnum was willing to cover not only news in the traditional sense, but to work with corporations to brand their activities as worthy of photojournalistic stories, much like the ones people were already used to seeing in Life magazine.”

In this way, photojournalism made its foray into the realm of public relations.

An image bigger than one artist

Bair was particularly interested in Magnum’s mode of production, arguing that its success resulted from a “decisive network” of agency staff, magazine editors, dark room developers, book publishers and museum curators that the photographers collaborated with on a day-to-day basis.

Indeed, her research challenges the persistent narrative of the ‘great artist photographer,’ which she said masks the collective efforts and infrastructure required to elevate the photojournalist to the status of an artist. It’s one thing to be able to take hundreds of photos on a shoot, she said, but without someone to edit the images, caption them, package them as a story and get it out the door, a photographer’s talent would go undiscovered.

“Although I’m an art historian, I’m much more interested in looking at the profession of photojournalism at this time and understanding how it worked than in analyzing a few famous images. To me, this was one of the biggest moments of innovation in the history of illustrated journalism and I want to capture the story behind the photographs.”

Nadya Bair found dozens of archives containing thousands of pages of correspondence, story scripts and caption notes that had never been analyzed. Here, a partial view of the voluminous archives of photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson at the Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris.

Bair received a 2015 Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellowship, which will fund her final year of writing before she defends her dissertation next Spring. The fellowship is given to 65 scholars nationally who are working in the humanities and social sciences, and Bair is one of only two art historians honored with the award this year.

To bring the day-to-day workings of Magnum Photos to light, she has conducted extensive archival research, visiting a dozen archives around the world and analyzing hundreds of pages of correspondence between Magnum photographers and their editors, book publishers and clients.

“Nadya Bair’s work is original, archivally rich and asks questions of importance to several disciplines, including art history and history,” said Vanessa Schwartz, professor of history and art history, and Bair’s thesis advisor. “It also exemplifies the interdisciplinarity for which USC Dornsife’s Visual Studies Research Institute is well-known and well-regarded.”

Bair hopes her research will encourage art historians who have grown used to writing about the singular artist and singular images to think about how the history of art and visual culture can be written from this very different perspective — one that takes the demands of the market seriously and that foregrounds production history and collaboration, regardless of the medium in which the artist works.

“I’m writing a lot of the people who have been written out of the history of photography back into it. For me that makes a more compelling history of the photojournalistic profession — it always included more than just the photographer.”