At the Edge of the Known World

Imagine what it was like for the first African to explore the New World in the 16th century. For Estebanico, a Moroccan slave, arriving from Spain in 1527 to what is now the United States’ Gulf Coast was bittersweet. Laila Lalami’s historical novel, The Moor’s Account (Pantheon, 2014), documents how Estebanico, a voyager with the famed Pánfilo de Narváez expedition, bears witness to the atrocities of conquistadors claiming land for the Spanish crown.

Within a year, the 600 members of the initial crew had been whittled down to four survivors, including Estebanico. From the coast, the small band made its way west across America’s vast interior to Mexico, pretending to be faith healers to survive.

Originally, the group’s experiences were chronicled by one of the survivors, a Spanish nobleman, who made no mention of women and little of Native Americans. Lalami, who earned her Ph.D. in linguistics from USC Dornsife in 1997, recasts the expedition through Estebanico’s eyes.

“The facts are the same, but the truth is different because you’re looking at it from a different perspective,” Lalami said.

Laila Lalami, who was born in Morocco, speaks Arabic, Spanish and French in addition to English. Her linguistics training informs her writing. “When you’re a writer everything you experience goes into your writing,” she said. Photo courtesy of Laila Lalami.

In this first chapter of The Moor’s Account, Estebanico chronicles his initial encounter with the lush, sandy shores of “La Florida” and its peoples, after sailing for months through treacherous conditions:

It was the year 934 of the Hegira, the thirtieth year of my life, the fifth year of my bondage — and I was at the edge of the known world. I was marching behind Señor Dorantes in a lush territory he, and Castilians like him, called La Florida. I cannot be certain what my people call it. When I left Azemmur, news of this land did not often attract the notice of our town criers; they spoke instead of the famine, the recent earthquake, or the rebellions in the south of Barbary. But I imagine that, in keeping with our naming conventions, my people would simply call it the Land of the Indians. The Indians, too, must have had a name for it, although neither Señor Dorantes nor anyone in the expedition knew what it was.

Señor Dorantes had told me that La Florida was a large island, larger than Castile itself, and that it ran from the shore on which we had landed all the way to the Peaceful Sea. From one ocean to the other, was how he described it. All this land, he said, would now be governed by Pánfilo de Narváez, the commander of the armada. I thought it unlikely, or at least peculiar, that the Spanish king would allow one of his subjects to rule a territory larger than his own, but of course I kept my opinion to myself.

We were marching northward to the kingdom of Apalache. Señor Narváez had found out about it from some Indians he had captured after the armada arrived on the shore of La Florida. Even though I had not wanted to come here, I was relieved when the moment came to disembark, because the journey across the Ocean of Fog and Darkness had been marred by all the difficulties to be expected of such a passage: the hardtack was stale, the water murky, the latrines filthy.…

I was also curious about this land because I had heard, or overheard, from my master and his friends, so many stories about the Indians. The Indians, they said, had red skin and no eyelids; they were heathens who made human sacrifices and worshipped evil-looking gods; they drank mysterious concoctions that gave them visions; they walked about in their natural state, even the women — a claim I had found so hard to believe that I had dismissed it out of hand. Yet I had become captivated. This land had become for me not just a destination, but a place of complete fantasy, a place that could have existed only in the imagination of itinerant storytellers in the souqs of Barbary. This was how the journey across the Ocean of Fog and Darkness worked on you, even if you had never wanted to undertake it. The ambition of the others tainted you, slowly and irrevocably.

The landing itself was restricted to a small group of officers and soldiers from each ship. As captain of the Gracia de Dios, Señor Dorantes had chosen twenty men, among whom this servant of God, Mustafa ibn Muhammad, to be taken on one of the rowboats to the beach. My master stood at the fore of the vessel, one hand on his hip, the other resting on the pommel of his sword; the posture seemed to me so perfect an expression of his eagerness to claim the treasures of the new world that he might have been posing for an unseen sculptor.

It was a fine morning in spring; the sky was an indifferent blue and the water was clear. From the beach, we slowly made our way to a fishing village one of the sailors had sighted from the height of the foremast, and which was located about a crossbow shot from the shore. My first impression was of the silence all around us. No, silence is not the right word. There was the sound of waves, after all, and a soft breeze rustled the leaves of the palm trees. Along the path, curious seagulls came to watch us and departed again in a flutter of wings. But I felt a great absence.

In the village were a dozen huts, built with wooden poles and covered with palm fronds. They were arranged in a wide circle, with space enough in between each pair of homes to allow for the cooking and storing of food. The fire pits that dotted the perimeter of the clearing contained fresh logs, and there were three skinned deer hanging from a rail, their blood still dripping onto the earth, but the village was deserted. Still, the governor ordered a complete search. The huts turned up tools for cooking and cleaning, in addition to animal hides and furs, dried fish and meat, and great quantities of sunflower seeds, nuts, and fruit. At once the soldiers took possession of whatever they could; each one jealously clutched what he had stolen and traded it for the things he wanted. I took nothing and I had nothing to barter, but I felt ashamed, because I had been made a witness to these acts of theft and, unable to stop them, an accomplice to them as well.

A finalist for the 2015 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, The Moor’s Account was named one of The New York Times Book Review’s “100 Notable Books of 2014.” and The Wall Street Journal’s “Best Books of 2014.”

As I stood with my master outside one of the huts, I noticed a pile of fishing nets. It was while lifting one up to look at its peculiar threading that I found an odd little pebble. At first, it seemed to me that it was a weight, but the nets had smooth stone anchors, quite unlike this one, which was yellow and rough-edged. Then I thought it might be a child’s toy, for it looked like it could be part of a set of marbles or that it could fit inside a rattle; it might have been left on the fishing nets by mistake. I held it up to the light to get a better look, but Señor Dorantes saw it.

Estebanico, my master said. What did you find?

Estebanico was the name the Castilians had given me when they bought me from Portuguese traders — a string of sounds whose foreignness still grated on my ears. When I fell into slavery, I was forced to give up not just my freedom, but also the name that my mother and father had chosen for me. A name is precious; it carries inside it a language, a history, a set of traditions, a particular way of looking at the world. Losing it meant losing my ties to all those things too. So I had never been able to shake the feeling that this Estebanico was a man conceived by the Castilians, quite different from the man I really was. My master snatched the pebble from my hand. What is this? he asked.

It is nothing, Señor.

Nothing?

Just a pebble.

Let me see. He scratched at the pebble with a fingernail, revealing, under the layer of dirt, a brighter shade of yellow. He was an inquisitive man, my master, always asking questions about everything. Perhaps this was why he had decided to set aside the comfort of his stately home in Béjar del Castañar and make his fortune in an uncharted territory. I did not resent his curiosity about the new world, but I envied the way he spoke about his hometown — it was, always, with the expectation of a glorious return.

It is nothing, I said again.

I am not so sure.

It must be pyrite.

But it might be gold. He turned the pebble around and around between his fingers, unsure what to do with it. Then, suddenly making up his mind, he ran up to Señor Narváez, who was standing in the village square, waiting for his men to complete their search. Don Pánfilo, my master called. Don Pánfilo.

I should describe the governor for you. The most striking thing about his face was the black patch over his right eye. It gave him a fearsome look, but it seemed to me his sunken cheeks and his small chin did not particularly reinforce it. On most days, even when there was no need for it, he wore a steel helmet adorned with ostrich feathers. Over his breastplate, a blue sash ran from his shoulder to his thigh and was tied with flourish over his hip. He looked like a man who had taken great pains with his appearance, yet he was also capable of the same coarseness as the lowliest of his soldiers. I had once seen him plug one nostril with a finger and send out a long string of snot shooting out of the other, all while discussing shipping supplies with one of his captains.

Señor Narváez received the pebble with greedy fingers. There was some more holding up to the light, some more scratching. This is gold, he said solemnly. The pebble sat like an offering in his palm. When he spoke again, his voice was hoarse. Good work, Capitán Dorantes. Good work.

The officers gathered excitedly around the governor, while a soldier ran back to the beach to tell the others about the gold. I stood behind Señor Dorantes, shaded from the sun by his shadow and, although I could not see his face, I knew that it was full of pride. I had been sold to him a year earlier, in Seville, and since then I had learnt how to read him, how to tell whether he was happy or only satisfied, angry or mildly annoyed, worried or barely concerned — gradations of feelings that could translate into actions toward me. Now, for instance, he was pleased with my discovery, but his vanity prevented him from saying that it was I who had found the gold. I had to remain quiet, make myself unnoticed for a while, let him bask, alone, in the glory of the find.

Moments later, the governor ordered the rest of the armada to disembark. It took three days to shuttle all the people, horses, and supplies to the white, sandy beach. As more and more people arrived, they somehow huddled around the familiar company of those closest to them in station: the governor usually stood with his captains, in their armor and plumed helmets; the commissary conversed with the four friars, all wearing identical brown robes; the horsemen gathered with the men of arms, each of them carrying his weapon — a musket, an arquebus, a crossbow, a sword, a steel-pointed lance, a dagger, or even a butcher’s hatchet. Then there were the settlers, among whom carpenters, metalworkers, cobblers, bakers, farmers, merchants, and many others whose occupations I never determined or quickly forgot. There were also ten women and thirteen children, standing in throngs beside their wooden chests. But the fifty or so slaves, including this servant of God, Mustafa ibn Muhammad, were scattered, each one standing near the man who owned him, carrying his luggage or watching his belongings.

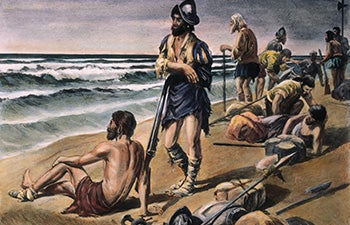

While writing The Moor’s Account, Lalami found that the Narváez expedition served as the inspiration for a number of paintings. However, as shown here in Alfred Russell’s depiction, these did not always include Estebanico. Image courtesy of the Granger Collection, New York.

By the time everyone had congregated on the beach, it was late afternoon on the third day, and the tide was low. The waves were small, and a dark strip of shoreline was exposed. The weather had cooled; now the sand was cold and sticky under my feet. High clouds had gathered in the sky, turning the sun into a faint, distant orb. A thick fog drifted in from the ocean, slowly washing the color out of the world around us, rendering it in various shades of white and gray. It was very quiet.

The notary of the armada, a stocky man with owlish eyes by the name of Jerónimo de Albaniz, stepped forward. Facing Señor Narváez, he unrolled a scroll and began to read in a toneless voice. On behalf of the King and Queen, he said, we wish to make it known that this land belongs to God our Lord, Living and Eternal. God has appointed one man, called St. Peter, to be the governor of all the men in the world, wherever they should live, and under whatever law, sect, or belief they should be. The successor of St. Peter in this role is our Holy Father, the Pope, who has made a donation of this terra firma to the King and Queen. Therefore, we ask and require that you acknowledge the Church as the ruler of this world, and the priest whom we call Pope, and the King and Queen, as lords of this territory.

Señor Albaniz stopped speaking now and, without asking for permission or offering an apology, he took a sip of water from a flask hanging from his shoulder.

I watched the governor’s face. He seemed annoyed with the interruption, but he held back from saying anything, as it would only delay the proceedings further. Or maybe he did not want to upset the notary. After all, without notaries and record-keepers, no one would know what governors did. A measure of patience and respect, however small, was required.

Unhurriedly Señor Albaniz wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and resumed speaking. If you do as we say, you will do well and we shall receive you in all love and charity. But if you refuse to comply, or maliciously delay in it, we inform you that we will make war against you in all manners that we can, and shall take your wives and children, and shall make slaves of them, and shall take away your goods, and shall do you all the mischief and damage that we can. And if this should happen, we protest that the deaths and losses will be your fault, and not that of their Highnesses, or of the cavaliers here present. Now that we have said this to you, we request the notary to give us his testimony in writing and the rest who are present to be witnesses of this Requisition.

Until Señor Albaniz had arrived at the promises and threats, I had not known that this speech was meant for the Indians. Nor could I understand why it was given here, on this beach, if its intended recipients had already fled their village. How strange, I remember thinking, how utterly strange were the ways of the Castilians — just by saying that something was so, they believed that it was. I know now that these conquerors, like many others before them, and no doubt like others after, gave speeches not to voice the truth, but to create it.

At last, Señor Albaniz fell silent. He presented the scroll and waited, head bowed, while Señor Narváez signed his name on the requisition. Facing the crowd, the governor announced that this village would henceforth be known as Portillo. The captains inclined their heads and a soldier raised the standard, a green piece of fabric with a red shield in its center. I was reminded of the moment, many years earlier, when the flag of the Portuguese king was hoisted over the fortress tower in Azemmur. I had been only a young boy then, but I still lived with the humiliation of that day, for it had changed my family’s fate, disrupted our lives, and cast me out of my home. Now, halfway across the world, the scene was repeating itself on a different stage, with different people. So I could not help feeling a sense of dread at what was yet to come.