‘Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing’

It was a beautiful spring day in Johannesburg. The year was 1994.

At the inauguration ceremony where Nelson Mandela took the oath of office as the first democratically elected black president of South Africa, the victorious tones of “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (“Lord Bless Africa” in Xhosa) filled the Union Buildings amphitheater in Pretoria. Beyond the rich sound, the pan-African liberation anthem was charged with profound symbolism.

During South Africa’s long decades of apartheid, the anthem was played at rallies and union events and helped to fortify and mobilize oppressed black Africans.

“It was the defining sound text of an aggrieved majority under siege,” said Shana Redmond, assistant professor of American studies and ethnicity (ASE) at USC Dornsife.

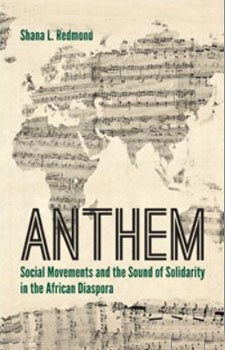

“Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” is one of six anthems of the 20th century that Redmond analyzes in her new book, Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora (New York University Press, 2014). Combining her passions social justice and music, Redmond investigates race and nation-making through music, and the idea of music as a performative political act.

In her research, she noticed a striking absence of conversation in black music studies in genres beyond hip-hop, blues and jazz.

“I found little to no literature on the anthem genre, particularly in the African American context, and so much of the diasporic literature on anthems is very nation-based,” Redmond said. “But to me, thinking about transnational exchange and transnational cultures was really interesting. I knew I wanted to work comparatively within the spaces and experiences of the African diaspora. The anthem genre opened that up for me in all of these perfect ways.”

Redmond’s book argues that analyzing the composition, use and performance of black anthems yields a more complex understanding of 20th century racial and political formations in America and beyond. It also explores how and why diaspora emerges as a formative conceptual and political framework of modern black identity.

The book distinguishes anthems from other genres of black empowerment, such as spirituals.

Shana Redmond’s research for her book took her to South Africa, where she studied the role of the anthem in the global African diaspora.

“Anthems are songs that were adopted and/or mobilized by social justice and protest organization. Spirituals were also songs of struggle, resistance and agency among African descendants, but were used on very local scales to incite and encourage rebellion. I was interested in thinking through the ways in which songs developed lives beyond their place of origin and how masses of people began to see themselves in concert — literally — with each other through the performance of these songs.”

Thus, when the crowd joined in singing “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” on that spring day in Johannesburg, the camaraderie represented one moment in a complex political history.

“United we shall stand,” they sang. “Let us live and strive for freedom, in South Africa our land.”

“The book focuses as much on performances as the music or the composition itself, because through the performance, these pieces are given life,” Redmond said. “Being able to see them performed in New York City or in Havana, Cuba, makes all the difference in thinking about how people understood themselves within a global system of domination.”

Other anthems explored in the book are “Ethiopia (Thou Land of Our Fathers),” mobilized by the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1920s New York; “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” the anthem of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; “Ol’ Man River,” a song reclaimed, rewritten and transformed into an anthem of the midcentury global justice movement by performer Paul Robeson; “We Shall Overcome,” a defining anthem of the Civil Rights Movement; and “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” one of Nina Simone’s 1960s anthems that articulated the Black response to injustices in a new way, transitioning from the rhetoric of the civil rights movement to that of the Black Power movement.

Since her arrival at USC Dornsife six years ago, Redmond has been awarded an Advancing Scholarship in the Humanities and Social Sciences fellowship by the provost’s office, which allowed her to travel to South Africa for a month to conduct the archival research for the book.

“I think one of this project’s strengths — something I hope any student or colleague who reads the book find — is illuminating the ways in which music and culture activate our sensibilities and minds and bodies in ways that can change the world.”