Five Hours of Terror

When the theme song from the movie Titanic boomed from speakers, Georgia Ananias remarked to her husband maybe that wasn’t the best song to play on a cruise ship.

An hour later, just as their dinner salads arrived at 9:45 p.m., the family heard rumbling followed by intense vibrations. It reminded them of the mini-earthquakes back home in Los Angeles. They became uneasy when they noticed the waterline in their glasses had settled at a distinct angle.

Then came a loud crash. The lights went off. In the blackness, pandemonium.

Earlier that day, Dean and Georgia Ananias and two of their three daughters, Valerie and Cindy, were thrilled to be embarking on the Costa Concordia for a Mediterranean vacation. They were treating themselves after all the planning leading up to their daughter Debbie’s wedding just a week prior. While the entire family normally traveled together, Debbie had stayed behind to visit friends in Miami before taking off for her European honeymoon.

Setting sail on Friday, Jan. 13, 2012 from the port of Civitavecchia on the Italian coast near Rome, the cruise was poised to stop in Greece and eventually take them on to Israel.

“For me, this trip was a journey back to my roots in Greece,” recalled Valerie, the eldest daughter who graduated from USC Dornsife in 2004 with a bachelor’s in sociology. “Greece is where my family had originally come from. I had so many hopes and dreams wrapped up in this trip.”

The great expectations came to a screeching halt when the Costa Concordia hit a huge reef during an unofficial, off-course salute to coastal residents.

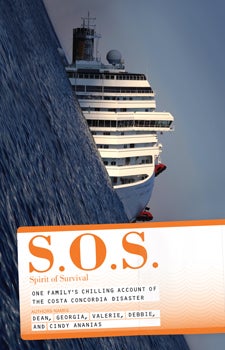

After the ordeal, the Ananias family wrote a book, S.O.S. Spirit of Survival, to share their story and advocate for safety changes in the cruising industry.

The Ananias family relied on their extensive experience traveling on cruise ships to keep calm. That meant contending with mass confusion, screaming passengers and an ill-prepared crew.

“There was no such thing as ‘women and children first’ in this situation,” Dean Ananias later recalled. “It was every man for himself.”

Life jackets were lacking, and eventually the family was forced to return to their room on a lower level of the ship — in the dark, not knowing if their feet would soon be sloshing through water — to get the jackets they knew were stored there. They refused to split up.

Once life jackets were secured, the family managed to jump on a lifeboat, only to be pulled up to deck again. The side of the ship they were on was tipped away from the water, making it impossible for the lifeboat to be lowered down without scraping against the ship’s hull.

For the first time, the family faced the prospect of death as they huddled together in the darkness, standing on what used to be the wall.

“We talked and prayed, waiting for the water to come, waiting to die,” Valerie said. “But for some reason, despite the situation we were in, I knew there was a way out. The way it felt waiting near that railing, I was certain of dying and living at the same time.”

Meanwhile, back in Florida, Debbie was frantically trying to reach her family with no success.

“At first I just went into freak-out mode,” recalled Debbie, who graduated from USC Dornsife in 2006 with a degree in psychology before earning a master’s from the USC School of Social Work in 2010. “Your heart just sinks. Your mind automatically goes to the worst scenario — my whole family is dead. But even though I didn’t know what was going on, I knew I needed to do something.”

She and her groom Jonathan and other family members could do little but keep calling the State Department and the American embassy in Rome to try and get information.

Back on the boat, as the ship listed just short of 90 degrees, it hit the rocky sea floor and stabilized. Valerie’s “way out” came in the form of a favorable wind that blew the vessel back in toward shore and not out to sea, where it would have capsized completely.

From left, sisters Cindy (Keck School of Medicine ’09), Debbie (USC Dornsife ’06 and USC School of Social Work ’10) and Valerie (USC Dornsife ’04) show their Trojan spirit. Photo courtesy of Debbie Ananias.

After five hours of terror, the four members of the Ananias family and the others finally managed to scale down the side of the ship to a lifeboat, which brought them to land. Of the more than 4,200 passengers on board, 32 lost their lives. Had wind conditions been less favorable, the potential death toll of the Costa Concordia shipwreck could have surpassed that of the Titanic exactly 100 years before, which numbered 1,517.

“I had to see them in the flesh to actually believe they were safe,” said Debbie, who rushed to the airport to meet them. “It was exuberance. I was so happy and relieved to see them.”

The experience made the Ananias family stronger. For Valerie, it gave her a deeper appreciation of what it means to step up and help others when crises arise.

The family has talked about the ordeal on the TODAY show, the Dr. Phil Show, KTTV’s Good Day LA and CNN. They collaboratively wrote the book S.O.S. Spirit of Survival, which is told from the point of view of each family member. In addition to recounting their harrowing tale, the book offers travel safety tips.

Following the tragedy, the Ananias family has joined a mission to advocate for improved cruise ship safety regulations. The accident was ultimately deemed the result of gross negligence.

“We don’t want the victims to have died in vain, so we needed to tell what really happened,” emphasized Debbie. “We want people to know that we need to make changes in this industry at the government and legislative levels.”

During the catastrophe, Valerie recalled how she was particularly worried about the children on board. She believes her compassion for children was strengthened during her work with youth at USC Dornsife’s Joint Educational Project.

“We paid special attention to the kids, not letting them be trampled or left behind during the chaos of abandoning the ship,” Valerie said.

“Being a Trojan, you always have a sense of commitment, strength, dedication and endurance, which are all things you need in order to survive any disaster. The expression, ‘Fight On’ became our driving force.”