A Nobel Victory

Fate was sealed after an off-the-cuff remark by Eliezer Finkman. Entering Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, a young Arieh Warshel asked his friend Finkman what he should study.

“Chemistry because you have good vision,” replied Finkman, an army buddy of Warshel’s who was already enrolled at the Technion.

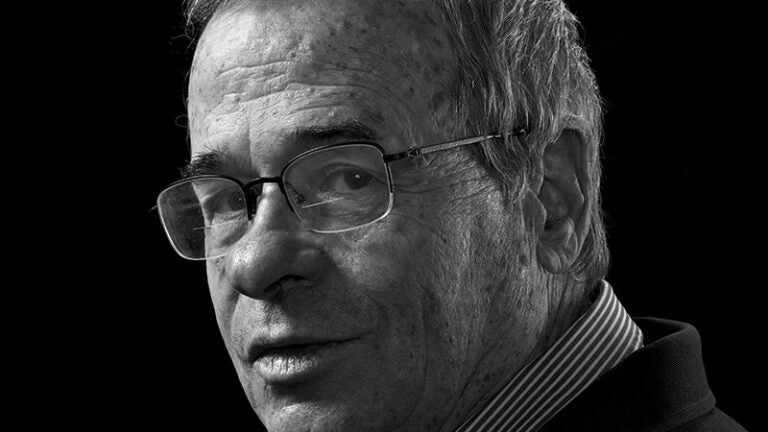

“He assumed since he wore glasses and I did not, I had good color vision,” Warshel, 72, recalled with a shrug. “He thought chemists should see well.”

Warshel filled out “chemistry” under field of study. What started out as a random choice became a lifelong obsession that culminated in October when Warshel won the 2013 Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

The groundwork began in the 1960s at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, where Warshel was a doctoral student. At Weizmann, Warshel started working with Shneior Lifson who had the vision that molecules should be modeled by computers.

Warshel began developing computer programs to find the structure of medium-sized molecules. He came up with an idea to write such a program in a general way, then in 1967 was joined by Michael Levitt, a pre-Ph.D. student. The pair tried something new and outlandish at the time. They developed an extremely powerful program that could calculate the structure and vibration of any molecule, including very large ones.

This program is the basis of all current molecular modeling programs today.

“There were experimentalists in Israel who heard I was taking big molecules and using our program to calculate vibrations,” Warshel recalled. “They said that was completely impossible.”

‘That’s Impossible’

To prove the impossible, Warshel first used a Golem computer built at Weizmann. The Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at USC Dornsife told his story inside his office, packed with books, computers, manila folders stacked high on his desk, and photos tacked on a bulletin board, including a few snapshots of his wife of 47 years, Tamar.

Sitting at a small table, leaping up to zip across the room and pull out a book or a photo to illustrate his story, Warshel often paused mid-sentence to offer insight on a topic.

He explained that the Golem name derived from a legendary anthropomorphic being created from inanimate matter in Prague of the Middle Ages. Warshel recalled hearing about Albert Einstein’s reaction to the suggestion to build Israel’s first computer preceding the Golem.

“Why does such a small country need such a big computer?” Warshel said, quoting Einstein with disbelief. “But [mathematician John] von Neumann said, ‘No, they need a computer.’ ”

At Weizmann, “We had a computer with the highest accuracy. This allowed me to check whether my first derivatives that describe the forces on the atoms — the key to the design of the general program — were correct. Instead of writing the formulas, I just tried to get the forces by seeing how the energy changes while moving atoms from left to right on the computer.”

After earning his Ph.D. in 1969, Warshel conducted postdoctoral research in the laboratory of Martin Karplus at Harvard University. Karplus used quantum mechanics to study very small molecules. Warshel had already experimented with adding a small quantum portion to the classical description of a medium-sized molecule. Warshel and Karplus decided to research medium-sized molecules with double bonds by combining the classical description from the Weizmann program with the quantum description of double bonds.

After Warshel returned to Weizmann as a senior scientist, Levitt, who had just earned his Ph.D., arrived. They continued collaborating and in 1976 published their seminal work while at the University of Cambridge, England. This work combined quantum and classical descriptions of molecules, which allowed them to describe actual chemical bonds breaking down inside enzymes.

It took the world four decades to catch up with the ideas of Warshel, Karplus and Levitt, who share the Nobel Prize.

“First, people would say that what you are doing is impossible,” Warshel said. “So this goes on for 10 years. Then they would say what you are doing is trivial. And then they would say they invented it first. So there was this process, which took a long time.”

Meanwhile, inside his USC Dornsife computation laboratory, Warshel has been using computer models to study how proteins transfer signals within a single cell.

“The experimental community was not so anxious to say that this was figured out by computation,” Warshel said. “And I’m going even farther by saying that you cannot even ask the questions without the computer. And in this respect, suddenly the Nobel Prize makes you [look] like a guru. So now, suddenly, I’m certified as correct.”

Wearing the glasses he didn’t need as a young man, Warshel gave his signature subtle smile with just the corners of his mouth turning up. If he appears to know something we all don’t that is because he does.

“Arieh could actually see into the future,” said Chi Mak, professor and chair of chemistry at USC Dornsife. “He persisted with his ideas for more than 40 years. He proved skeptics wrong and his vision absolutely right.”

After Warshel’s breakthrough four decades ago, the sentiment in the field of chemistry slowly began to shift, Mak said. “There is now more credence given to theoretical chemistry.”

Warshel is a creative thinker, Mak said.

“When you’re that creative your ideas often don’t catch on very quickly,” he said. “He thinks different. That’s a hallmark of a genius. But sometimes it’s so different, it’s hard to catch on or buy into. That’s why Arieh has always been a fighter. He’s fought extra hard to get his ideas rooted into the community.”

An Original

Two USC Dornsife professors were key in drawing Warshel to the university in 1976. In the 1970s, Gerald Segal, professor of chemistry at USC Dornsife, gave a talk at Weizmann, where he met Warshel, by then an assistant professor.

“He was clearly a capable and interesting character on the horizon,” recalled emeritus professor Segal, who was chemistry chair at the time and later became USC Dornsife dean. “His work was very unusual. It caught my eye.”

Segal recounted the reaction of Martin Kamen upon meeting Warshel during interviews. Kamen, professor of biological sciences and chemistry at USC Dornsife, had co-discovered radioactive carbon-14, which revolutionized biochemistry.

“This guy is fearless,” Segal remembered Kamen telling him. “He just might find something out.”

USC Dornsife Distinguished Emeritus Professor Otto Schnepp taught at the Technion in the 1960s. One of his students was Warshel. Schnepp joined USC in 1965, and later became a visiting scientist at Weizmann, where Warshel was a graduate student. The two published a paper on the vibrations in molecular crystals.

“I recognized he was a very smart guy,” Schnepp said. “He was looking for a permanent position and he visited USC. He made a good impression on the faculty so we recruited him. The first thing that impressed people was that he’s very bright and he has a good sense of humor.

“He always shows originality.”

Warshel reflected that Schnepp, Segal and Philip Stephens, professor emeritus of chemistry, the latter who died in 2012, were the main reasons he chose USC Dornsife.

Since arriving in 1976, Warshel has been elected to the National Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society of Chemistry, and has published more than 350 scientific papers. He has also perfected methods being used on a practical level to develop new drugs. Today, Warshel’s methods are being used to predict the interaction between pharmaceuticals and their drug targets. This allows drug designs that supersede empirical experimentation.

“I’m a strong believer that understanding enzymes can help to find better treatment for diseases than experimenting in a blind way,” Warshel said, using as an example improving chemotherapy to fight cancer. “If you find a molecule that is really effective and is exactly in the right point in the process that leads to rapid cell division and to cancer, it can be used to create much less painful side effects in chemotherapy.”

G.K. Surya Prakash, professor of chemistry and USC Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute director, stressed that Warshel’s prize-winning research was conducted at USC.

“His science has stood the test of time,” Prakash said.

Considered the “Sherlock Holmes of chemistry,” Warshel continues to study enzymes leading to more breakthroughs.

“Like any great detective, Arieh is driven by his curiosity,” USC Dornsife Dean Steve Kay said. “His Nobel Prize not only places him among the world’s most elite scholars, but provides a wonderful example of the value of fundamental scientific inquiry.”

A Kibbutznik at Heart

Warshel was born Nov. 20, 1940, at Kibbutz Sde-Nahum in northern Israel. Like most kibbutzim, agriculture and factory work are the primary income.

Growing up, Warshel’s major duty after his studies was working in the fishponds and some weekends picking cotton in the fields. He mainly tended to the large pond, catching carp, which was later sold.

Warshel’s father, Tzvi, was also a kibbutz carp fisherman. Despite having only an elementary education, Tzvi became the accountant. Warshel’s mother, Rachel Spreicher, graduated from high school and worked at the kibbutz as a launderer, goat cheese churner and in the “shaldag” — the canned fish and grapefruit factory. She was also an elementary school teacher’s aide. Tzvi and Rachel met on the kibbutz, married and had four sons, the eldest Arieh.

Both sides of Warshel’s family descended from Poland. Tzvi Warshel, Rachel Spreicher and their family who survived the Holocaust did so by immigrating to the then-British-ruled Palestine. Most of Tzvi’s immediate family perished in 1941 in Lachowicze, Poland, when the Nazis assembled all Jewish inhabitants into the marketplace, where they were murdered. Rachel’s mother and two sisters also perished in the Holocaust.

Warshel was not the first in his family to excel in the sciences. His paternal aunt, Chana, studied engineering at the Technion as the first family member to enroll in college. After returning to Poland, she was killed in Lachowicze along with her grandfather, grandmother and other family.

Finishing what Chana began, Arieh became the first family member to graduate from college.

A dual citizen of the United States and Israel, Warshel fought in the Israeli Army as communications officer of a tank regiment during the June 1967 Six-Day and October 1973 Yom Kippur wars, then became a reservist. A scar on his right ear is a reminder of his close brush with death when a bullet pierced his helmet.

Photos taken before he joined the army show Warshel with a thick head of dark hair and a cool yet vulnerable expression that earned him the nickname of “a young James Dean.” He met Tamar “Tami” Fabrikant through her cousin who was Warshel’s classmate at the Technion. They wed in 1966 and have two daughters, Merav and Yael.

Those close to Warshel say he brought his fighting spirit and work ethic to his computation lab at USC Dornsife. A few days after his Nobel Prize was announced, Warshel was toiling in his lab with his students.

For Warshel, getting to this point has been a pilgrimage.

“To say this is sweet revenge would be wrong,” Mak said. “For Arieh, this is sweet victory.”

Yael Warshel contributed Warshel family history to this report.

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2013-Winter 2014 issue