L.A.’s Vernacular Landscapes

There is a tendency among my friends in Chicago, where I lived for the past eight years, to not see a Los Angeles beyond the Hollywood glitz and the tales of horrible traffic and bodily artificiality.

And before making L.A. my home a little over two months ago, I was less equipped to argue otherwise. But I always suspected that the city held more than met the eye, and so far my experiences here have corroborated these suspicions. In many ways, L.A. is a place that defies preconceived notions.

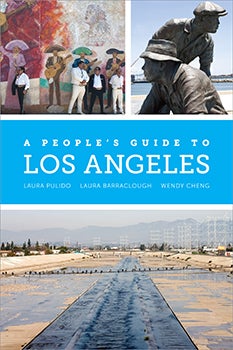

Laura Pulido, professor of American studies and ethnicity in USC Dornsife, collaborated with two of her former Ph.D. students, Laura Barraclough and Wendy Cheng, to create a different sort of L.A. guidebook, one that stands in stark contrast to the more traditional variety. As the newest transplant to the city at our office, I was given the privilege of talking with Pulido about her new book, A People’s Guide to Los Angeles (University of California Press).

Pulido’s target audience for this book certainly includes newcomers like me, though it’s also very much intended for native Angelenos who thought they’d seen it all. We agreed to meet at one of the sites listed in the guide, and Pulido selected an otherwise nondescript hilltop known as Little Round Top, east of the city in Altadena.

That morning, I’d awoken to the kind of bleak, overcast sky that reminds me all too well of long winter days in Chicago. Only here, as I’m beginning to recognize, by 9 or 10 a.m. the grey inevitably gives way to sunshine and impossibly blue skies. Following the navigational directions in the guidebook, I parked on the dirt roadside that extends beyond the dead-end of Rising Hill Road, where Pulido was waiting for me. Wearing jeans and a T-shirt in preparation for our short hike, she greeted me cheerfully and led the way in the coolness of the morning to the hill’s summit.

An abolitionist’s son, Owen Brown is buried at one of these two spots at the summit of Little Round Top hill. The headstone was stolen from the gravesite in 2002.

Marveling at the panoramic views, we soon found ourselves at the gravesite of Owen Brown. Abolitionist John Brown’s notorious unsuccessful raid on the federal armory at Harper’s Ferry in 1859 led to his capture and execution. The younger Brown also participated in this raid, but managed to escape by heading west into the wildlands of 1860s California. A marker that read: “Owen Brown, Son of John Brown, the Liberator, died Jan. 9, 1889” was stolen from the gravesite in 2002.

“It kind of blew me away when I first heard the story — ‘why would Owen Brown be buried in Altadena, California?’ ” Pulido said. “I read a story about this site in a history book of the area and thought, ‘Oh my god, where is this place, I have to find it.’

“From what I’ve heard, in the years following Owen Brown’s death there were regular visits here — he was a very important person because of his father and his participation in the raid. Pasadena, where Brown lived the last years of his life, has a longstanding African American community that appreciated the significance of Brown and held him in great esteem and respect. So it’s a really interesting connection between Southern California and Civil War history, and a much larger story in terms of U.S. History.”

Looking out at the earthy palette of the landscape and the faraway silhouettes of downtown L.A., I couldn’t help wondering, how many people would have ever known about this site? Especially considering the disappearance of the gravestone, which in effect obscures a legacy.

So often people think of L.A. in terms of its 20th century incarnations, but standing here drinking in the mountain views, you start to think about the history and the spirit of adventure that drew 19th century Easterners to this “novel” land. Long before MGM and Marilyn Monroe are the historical layers of the gold rush and the building of the transcontinental railroad as America forged its identity. Surveying this undeveloped landscape blanketed by rugged chaparral vegetation, your sense of the city’s geography expands and you start to imagine even further back in time.

I began to comprehend the breadth and depth of what “Los Angeles” really is.

This guidebook shows how power operates in the shaping of places in Los Angeles, and how power remains embedded in the vernacular landscapes.

A People’s Guide is a deliberate recasting of the way that L.A. is commonly known and experienced, emphasizing the inherently political nature of assigning value to people and places of historical and contemporary note. This nontraditional guide is also the product of nearly 15 years of collecting sites discovered through Pulido’s personal and academic research.

In the introduction, Pulido discusses how guidebooks select and interpret sites, representations that highlight certain perspectives while completely overlooking others. In order to offer an alternative narrative of a physical space, an explicit goal of the book, an appreciation for vernacular landscapes is required — landscapes of the ordinary and everyday.

“If you look at most tour guides for L.A., they focus very heavily on the Westside and downtown,” Pulido pointed out. “Very few will extend to the San Gabriel Valley, let alone south L.A. or the San Fernando Valley. We were really striving for geographic diversity to cover all parts of the county.”

Far afield of the glitz and glamor of Rodeo Drive and Hollywood Boulevard, the guide is filled with accounts of political struggle and marginalized sites of significance, some of which are quite shocking. One destination in El Monte is the housing complex where a group of 72 Thai immigrants were enslaved for nearly four years as garment workers before being rescued in a federal police raid.

The guide also tells the story of Chavez Ravine, an area just north of downtown L.A. and currently the site of Dodgers Stadium. Newcomers may not know that this area was once home to a robust Mexican American community that included the Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop neighborhoods. After WWII, the population boom compelled city officials to devise a new housing plan to redevelop what they considered to be “blighted” areas.

Existing residents were promised affordable new housing and residential priority. But not all Cold War-era Angelenos were interested in promoting affordable housing, and political tensions gave rise to a battle that lasted nearly a decade. Ultimately, the city’s police force, citing eminent domain, forcibly evicted residents and bulldozed the neighborhood. Adding insult to injury, opponents of the affordable housing development managed to shoot down the initiative, and the vacant land was eventually sold and built into Dodger Stadium.

“In this guide, our lens is power — looking at struggle, conflict in a landscape, how it shapes the city, the geography of the place,” Pulido said. “I think it’s very important to see an alternative narrative to the area.

“We really aim for being generative, hoping to inspire other people to produce their own kinds of tour guides that will take up where we left off.”

Exploring the guide, it’s immediately clear that you don’t have to be from out of town to gain a new understanding of L.A. and the many competing histories and identities that shape it. I look forward to forthcoming visits from my Chicagoan friends — who will surely visit during the winter months — and I’ll take pride in showing them an L.A. they will not expect.

Laura Paisley joined the USC Dornsife Office of Communication in July. In addition to writing, she manages the USC Dornsife Web site, DornsifeConnect and other e-communications. She arrived from Chicago, where she worked in communications roles at Northwestern University and Columbia College Chicago. She is looking forward to her first L.A. “winter.”