One of the Gang

During his fieldwork one evening in Los Angeles, Thomas Ward found himself staring down the barrel of a gang member’s gun.

His brush with death was a promise and a threat — Ward better pass the gang’s background check or else.

Though the incident was a sobering reminder of the dangers of participant-observation fieldwork with hardcore gang members, USC Dornsife’s Ward, associate professor of teaching in anthropology, wasn’t deterred from completing his ethnography of the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13.

Ward spent the better part of 16 years inside what is considered one of the world’s largest gangs.

He drank with gang members at parties, baked birthday cakes for them and met their families. He visited them in hospitals after they were shot or stabbed and visited them in prison after they were convicted. He also attended their funerals. They told him about their dreams and motivations.

Ward became close with a dozen hard-core gangsters as he interviewed more than 150 gang members from eight different cliques during the course of his fieldwork in Los Angeles, state prisons, Salvadoran prisons and the homes of retired gang members in El Salvador.

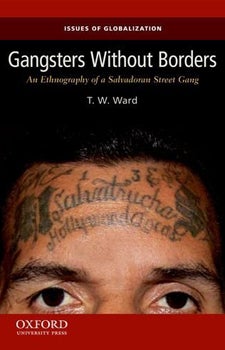

The fieldwork culminated with the just-released Gangsters Without Borders: An Ethnography of a Salvadoran Street Gang (Oxford University Press), which provides insight into the world of street gangs.

Though it’s often the subject of movies and documentaries, and it’s been glorified in gangster rap, much of gang life is misunderstood because of the subculture’s clandestine nature, according to Ward.

“Gangs are an inextricable part of American life,” he said. “Yet there is still a large gap between the reality of street gangs and the public perception of what it means to be a gang member.”

Ward began his research in 1993 by meeting with five active members of the gang in Los Angeles. Subsequently, two of the members died from gang violence, one recovered from crack addiction and another is serving life in prison. Those initial connections led Ward into the hard, fast life of hardcore gangsters.

Over the years, he had candid conversations with gang members, from the time of their initiations until long after when they were thinking about leaving la vida loca, or the crazy life, the Spanish term gang members often use to describe their lifestyle. Ward discovered that gang members were often allowed to retire after a few years of service with the gang and move on to a full-time job and family responsibilities.

Using a variety of ethnographic techniques, including formal and informal interviews and observations in a number of different settings, Ward was able to document the complexity of their lives over the course of their time with the MS-13.

While Ward was invited to sell drugs, commit robberies, participate in drive-by shootings and even become an honorary member of the gang, he always declined to participate in illegal activities.

Before immersing himself in the street gang subculture, Ward spent 14 years researching homeless people living on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles. He also explored the city’s Salvadoran immigrant community.

Ward first started working with the Salvadoran community in 1981 while volunteering with a social service agency that provided food, shelter and legal services for Central American refugees fleeing their war-ravaged country.

The experience would prove valuable: Ward learned about Salvadoran history and culture, including their slang, which helped him earn trust among the MS-13 members. But this background only provided a thin veil of protection when Ward had a gun put to his head and a knife held against his throat with the warning that he would be killed if he were an undercover cop. The gang members didn’t take Ward’s word for it — they did a background investigation by calling his employer and checking out his references in Los Angeles.

Despite death threats, Ward saw a human side to the MS-13 members, people who had lived difficult lives and were searching for something better. They longed for familial connections, status and self-respect.

“If gang members see no hope in their future, nothing is going to change,” Ward said.

The MS-13 gang was born during the bloody civil war in El Salvador. Refugee children were illegally smuggled into Los Angeles in the early ’80s and ’90s. Many of the young people were separated from their parents, did not speak English and were traumatized from having seen the atrocities of warfare.

To cope with their unfamiliar and sometimes hostile environment, the boys and girls formed Mara Salvatrucha, which roughly translates to Watch Out for Us Salvadoran Gangsters.

What started as a group for self-protection morphed into a predatory gang involved in crime, drugs and violence and to make money while widening their territory. But always, Ward said, there was a sense of family, belonging and purpose.

Many of the gang members end up in prison, which they call “a finishing school for crime,” Ward said. Most of them are undocumented immigrants and are vulnerable to deportation to El Salvador.

Those who were deported back to the war-torn country of their youth, where grenades can be bought for $2, found respect in being an L.A. gangster. And they found fertile ground for starting new gangs.

“The street gang subculture was an American export to Central America,” Ward said.

For his book Gangsters Without Borders: An Ethnography of a Salvadoran Street Gang, USC Dornsife’s Thomas Ward interviewed more than 150 gang members from eight different cliques.

Before beginning his research, Ward had seen gangs through the eyes of the nightly news, film and television, and he believed in the stereotype that gang life was fast, furious and filled with drugs, women and money. Though the media has dubbed MS-13 as “one of the world’s most dangerous gangs,” Ward said that this unquantifiable label is not only meaningless, it also unintentionally helps the group recruit new members.

“Street gangs thrive in the poorest neighborhoods in our urban communities,” he said. “They are highly complex social organizations that serve multiple functions. Some gangs are like deviant social clubs providing camaraderie, excitement and entertainment. Other gangs are like paramilitary organizations that provide protection and opportunity for economic gain and status. Most youth join street gangs in their search for a particular quality of life, a sense of self-worth and a sense of belonging to a group that cares about their welfare and survival.”

Ward’s firsthand research focused on gang members’ struggle for survival and status and their emotional connections with one another.

“The overarching goal of this research was to get into the heads and hearts of these Salvadoran immigrants, to understand the motives for their behaviors and to document the complexity of their gangster lives,” Ward said. “Without an understanding of the context of their behavior, we will not be able to solve the problems created by street gang members.”