People Who Need People

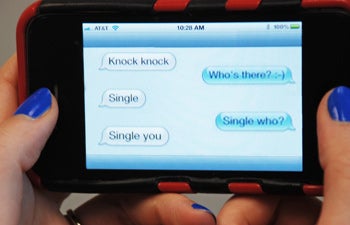

In the old days, we poured our hearts out in “Dear John” letters. Now, breaking up is easy. Just send a text: “Dear Baby, Welcome to Dumpsville. Population: You.”

Instant messaging, texting, Facebook and Twitter have changed the way we tell our cuddle muffins we’re just not feeling it anymore.

Speaking to an audience of mostly USC students, Ilana Gershon examined the changing rules of romance amid the culture of new media. Gershon, associate professor of communication and culture at Indiana University, interviewed 72 undergraduates — 54 women and 18 men of various ethnicities — who shared their stories about being decoupled via e-mail and similar forms of communication.

The talk was part of USC Dornsife’s 2011–12 Streisand Professor Lecture Series, “Where Is The Love?” The series featured five prominent scholars and writers whose work illuminates the shifting terrain of intimacy and love in American society.

“People often assume that the realm of the intimate is dwarfed in importance by bread-and-butter — or financial — issues,” said Alice Echols, Barbra Streisand Professor of Contemporary Gender Studies, Gender Studies Program chair, and professor of English, gender studies and history. “However, as this lecture series demonstrates, love, intimacy and sexuality are themselves material, preoccupying, life saving and life changing for us all.”

During a recent Streisand Professor Lecture Series event, author Ilana Gershon discussed the growing trend of saying au revoir to your loved one via texting, Facebook and Twitter. Photo by USC Dornsife.

The series kicked off in October with essayist, biographer and memoirist Vivian Gornick speaking about the vicissitudes of love and intimacy. In November, Lois Banner, professor of history and gender studies in USC Dornsife, discussed the ways in which Marilyn Monroe, an icon of white American femininity, rebelled against the gender and sexual rules of her day.

In January, Stephanie Coontz, a leading historian of the American family, examined women’s changing status, from the 1920s onward and identified new mystiques facing men and women today.

In March, Gershon, author of the critically acclaimed, The Break-Up 2.0: Disconnecting Over New Media, told the audience that the subject piqued her interest when she asked students to write down what they thought constituted a bad break-up during a linguistic anthropology class exercise.

“I was expecting stories about infidelity, about DVDs that were never returned, or loud, dramatic arguments,” Gershon said. “I did not expect what actually happened — everyone answered ‘breaking up by e-mail’ or ‘breaking up by text.’ ”

Curious about why the mediums used in break-ups are so important, Gershon launched her investigation.

“It wasn’t until after I had collected many break-up stories that I realized my students had told me something quite revealing that would come up time and time again when I interviewed their peers — American undergraduates focus on the ‘how’ when describing their break-ups, not the ‘why’ or the ‘who.’ ”

People in other countries are not as preoccupied with the mediums used when telling their stories about the disintegration of romantic relationships, she said.

Alice Echols, Barbra Streisand Professor of Contemporary Gender Studies, Gender Studies Program chair, and professor of English, gender studies and history (left) and Ilana Gershon, author of The Break-Up 2.0: Disconnecting Over New Media, at Gershon’s speaking event at USC. Photo by Pamela J. Johnson.

In England, people don’t appear to care as much about the ways in which their relationship ended, Gershon said, citing another study. Instead, character is important, not method. People are more concerned about justifying their decisions and being seen as good people despite their willingness to end relationships. Pointing to a different study, she said people in Japan tend to focus on issues of too much dependence or too much independence in their break-up narratives.

These were not issues Gershon’s interviewees broached.

“The fact that someone wants to end a relationship does not make the dumpee the victim,” she said. “It is the way the break-up is done that turns someone into the aggrieved party.”

Further, text break-ups often turn into detective stories in which recipients have to piece together a series of ambiguous and unclear conversations in to an overarching narrative to reveal whether a break-up has even occurred, she said.

“By focusing on the ‘how,’ those I interviewed are also reflecting on the ways in which the etiquette surrounding new media is by no means widely agreed upon,” Gershon said. “The rules are yet to be determined.”

The lecture series is part of an effort that began 27 years ago, when singer, actress and philanthropist Barbra Streisand endowed a USC Dornsife professorship in gender studies with a focus on the intersection of sexuality, intimacy and power between American men and women.

Streisand, who attended the Coontz lecture and dinner that followed, has been pleased with the content of the series.

“Her staff noted that Barbra framed the [lecture series] poster,” Echols said.

The series concluded April 9 with sociologist Paula England, among the most influential gender scholars of our time, discussing America’s changing family patterns, sexual behavior and labor markets.